KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The international community is left without a unified framework to curb plastic production following the collapse of the world’s first legally binding plastics treaty.

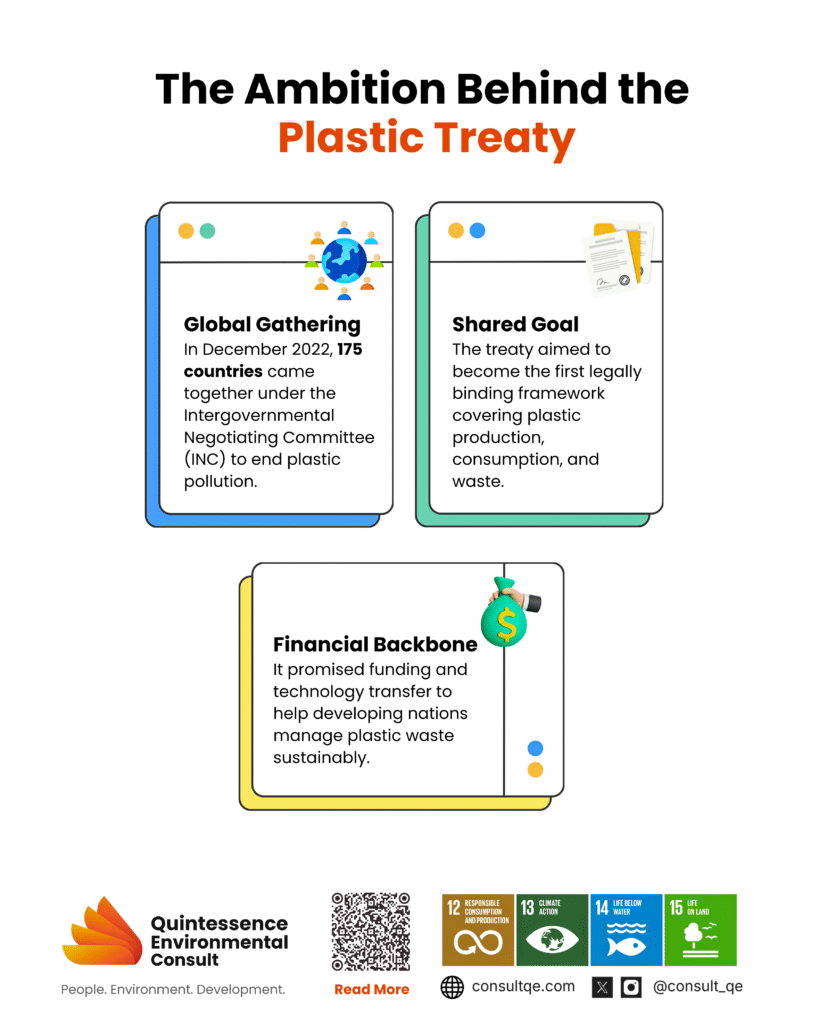

- One of the reasons for the collapse includes disagreement over the scope of the agreement- upstream control particularly curbs in plastic production, vs. downstream control (waste management).

- Another reason relates to the sharing of the burden, such as funding and technology transfer between developed and developing countries.

- The implications of the collapse for Nigeria include increased inflow of plastic waste into the country, as well as loss of funding and technology transfer that the agreement could have brought.

INTRODUCTION

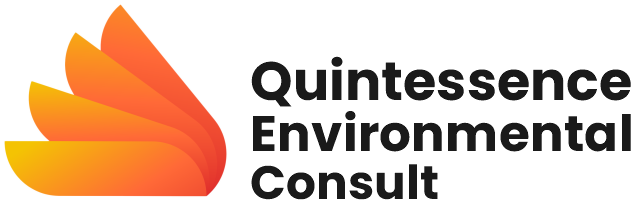

Each year, the world produces over 400 million tonnes of new plastic. In the absence of significant policy reforms, this figure is projected to increase by nearly 70% by 2040, according to a 2024 OECD policy scenario report 8. The proposed Global Plastic Treaty aims to address plastic pollution across its entire lifecycle, covering production, consumption, waste management, and disposal. In addition, the treaty is expected to provide funding and technology transfer to support plastic waste management.

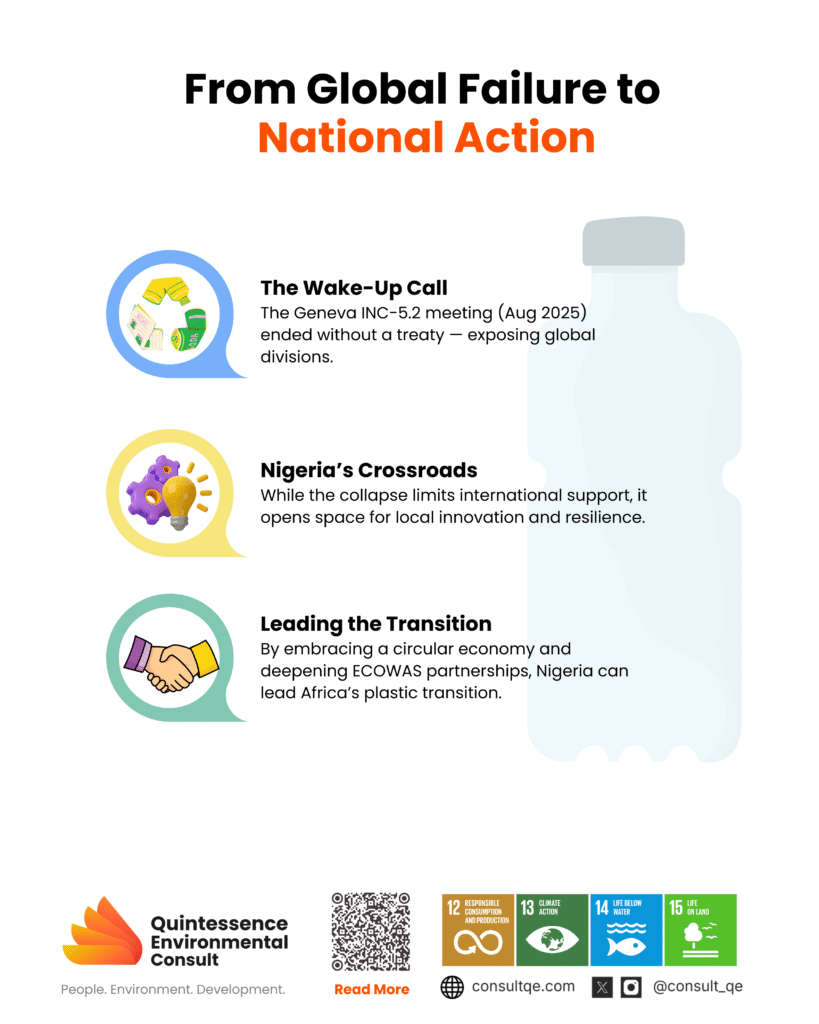

Formal negotiations on the treaty were led by the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC), which commenced in December 2022, with representatives from 175 countries participating. In addition, major financial institutions were expected to play a key role in promoting the development and implementation of the treaty within the global financial sector 5. However, following the final round of talks (INC-5.2) 7, held in August 2025 in Geneva, Switzerland, the Committee failed to reach a unified position. The breakdown of these negotiations has left the international community without a comprehensive, legally binding framework to effectively tackle the escalating plastic pollution crisis. A major impediment to progress was the INC’s reliance on consensus-based decision-making—a diplomatic mechanism that enables individual delegations to delay or obstruct collective outcomes. Attempts to reform this approach, including proposals for qualified majority voting in specific contexts, proved politically contentious and ultimately unsuccessful. Consequently, a small number of dissenting states were able to stall the entire negotiation process. This paper explores the main factors contributing to the negotiation deadlock and assesses the broader implications for Nigeria, one of Africa’s largest producers of plastic waste.

WHY THE TREATY COLLAPSED — THE MAIN CAUSES

1. Disagreements of Production Limits vs. Waste Management

More than 100 countries, including the UK and the EU bloc and many NGOs, argued for a full-lifecycle approach, including cutting production of virgin plastic. However, this approach was opposed by several countries whose economy is closely tied to petrochemicals, including Saudi Arabia, Russia and the United States1. Relevant sections include articles 4,5, and 5 of the chair’s draft text.6

2. Conflict over Burden-sharing

Developing countries pushed for firm commitments on finance, technical assistance, and capacity-building to help them transition away from polluting practices. Wealthier countries were reluctant to accept binding, large-scale financing or legally enforceable transfer mechanisms, creating an impasse over who pays for implementation. 4 Relevant section is Article 11 of the Chair’s draft text. 6

3. Technical and Definitional Disputes (chemicals, recyclability claims, metrics)

About 16000 chemicals are known to be associated with plastics, and over 4200 are categorized as chemicals of concern. 3 Some countries and negotiators want the treaty to include clear provisions to phase out or regulate certain high-risk additives, while other countries (often major plastics- or petrochemical-producing ones) resist binding upstream controls on additives.

IMPLICATIONS FOR NIGERIA

The collapse of the global plastics treaty poses serious setbacks to Nigeria’s ability to manage plastic waste effectively. Without an enforceable international framework to control plastic production and the use of toxic additives, Nigeria is less likely to receive the coordinated, large-scale funding and technology transfer needed to tackle plastic pollution. Specifically, the country could be confronted with:

- Increased exposure to low-cost, non-recyclable plastics would likely result in Nigeria continuing to receive large quantities of single-use plastics and products containing hazardous chemical components, further burdening the country’s already inadequate waste management systems.

- Market instability for informal waste collectors, who are vital to recycling efforts but are exposed to hazardous chemicals and often operate in unsafe conditions.

- Absence of a coordinated international mechanism which would limit Nigeria’s access to critical financial and technological support needed to advance sustainable waste management practices.

WHAT NIGERIA CAN DO IN THE FACE OF THE FAILED TALK

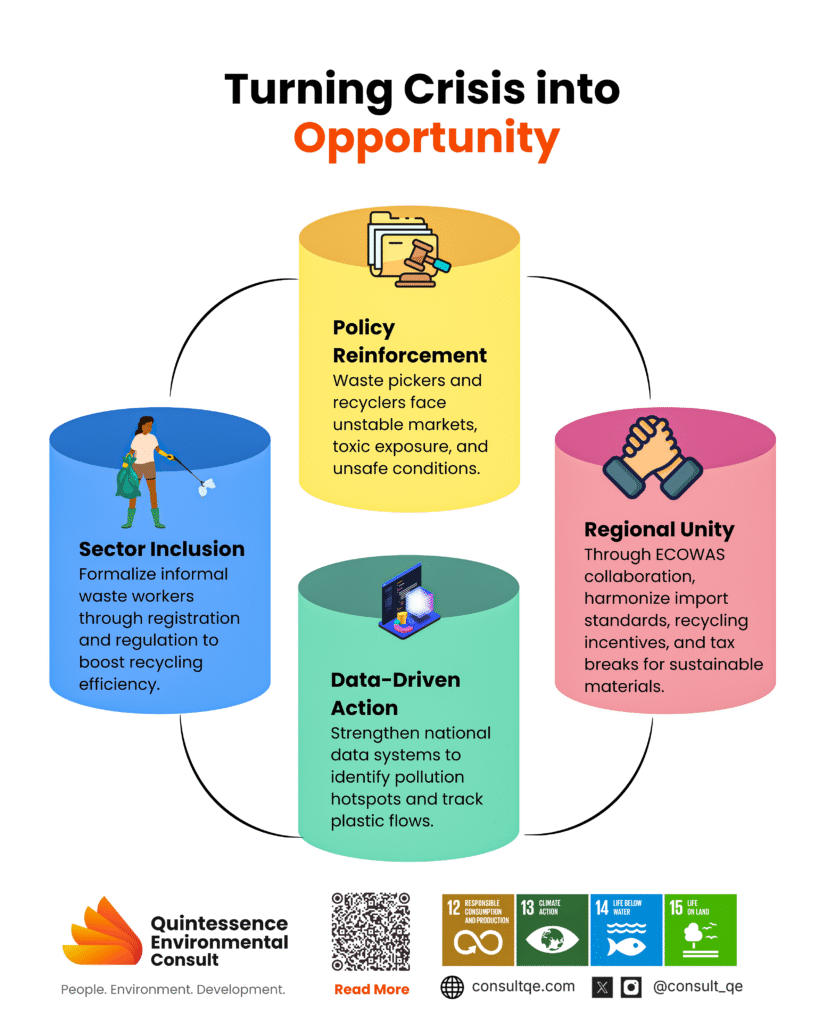

In the wake of the collapse of the Global Plastic Treaty, Nigeria can adopt a comprehensive national strategy for plastic waste management by strengthening policies that target both the upstream and downstream dimensions of the issue. Encouragingly, the country has already taken notable steps in this direction. The 2020 National Policy on Plastic Waste Management embraces a life-cycle approach, aiming to phase out Styrofoam and single-use plastics between 2025 and 2028, reduce plastic waste generation by 50%, and ensure that all plastics in circulation are recyclable and biodegradable by 2030 2. However, implementing these measures across Nigeria’s federal system presents significant challenges, particularly at the subnational level. The collapse of the treaty also deprived Nigeria of crucial international support that could have enhanced the execution of its national policy. Consequently, the country must now depend on domestic initiatives and resources to address its plastic waste problem. Key actions that could help Nigeria strengthen its current efforts include:

- Strengthening national policy which prioritize upstream measures such as product design-for-recycling and restrictions on toxic additives, as well as single-use plastic. Downstream measures such as Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) rules should be strictly enforced.

- Integrating the informal waste sector into the formal system through mandatory registration and standardization. Formalization may attract funds, thereby improving the overall waste management efficiency.

- Improving national data on plastic flows, hotspots, and the presence of hazardous additives and microplastics.

- Strengthening of regional collaboration through ECOWAS. Countries within the region can harmonize standards and import controls. Member nations can also harmonize incentive measures such as tax breaks for recycled products and safer or biodegradable alternatives.

CONCLUSION

The failure of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) to reach a unified position on the Global Plastic Treaty in Geneva in August 2025 leaves the international community without a legally binding framework to tackle the rapidly escalating plastic pollution crisis, revealing deep-seated divisions among member states. For Nigeria, this outcome poses significant challenges to its plastic waste management ambitions, particularly as it reduces access to crucial international support for funding and technology transfer; however, it simultaneously creates an opportunity for the country to strengthen domestic policies and rely on a robust, coordinated national strategy and regional cooperation to address its mounting plastic waste challenge. By strengthening national policies, formalizing waste management systems, investing in recycling infrastructure, and deepening regional partnerships through ECOWAS, Nigeria can chart an independent path toward a resilient circular economy—even in the absence of a global agreement.

REFERENCES

- Cocksedge, R. (2025) ‘Plastics treaty: UN delegates meet to finalise pollution plan’, BBC News, 21 August. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/

cvgpddpldleo. - Federal Ministry of Environment (Nigeria) (2021) National Policy on Plastic Waste Management. Available at: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/nig214338.pdf.

- Global Chemical Transparency (2025) INC5.2 information paper 1. Available at: https://www.globalchemicaltransparency.org/

wp-content/uploads/2025/04/INC52-information-paper-1.pdf. - Jha, M. (2025) ‘Global Plastic Profiles 2025: Article 11 on the means of implementation is a complex and unresolved area of the treaty text’, Down to Earth, 19 August. Available at: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/waste/global-plastic-profiles-2025-article-11-on-the-means-of-implementation-is-a-complex-and-unresolved-area-of-the-treaty-text.

- UNEP FI (2023) New Finance Leadership Group to support development of international agreement to end plastic pollution. Available at: https://www.unepfi.org/industries/banking/new

-finance-leadership-group-to-support-development-of-international-agreement-to-end-plastic-pollution/. - UNEP (2025) Chair’s draft text proposal. 13 August. Available at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/

chairs_draft_text_

proposal_13_august_2025_14.48.pdf. - UNEP (2025) Session 5.2. Available at: https://www.unep.org/inc-plastic-pollution/session-5.2.

- OECD (2024) Policy scenarios for eliminating plastic pollution by 2040. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/policy-scenarios-for-eliminating-plastic-pollution-by-2040_76400890-en.html.