KEY TAKEAWAYS

- In Nigeria, ASM accounts for over 70% of Nigeria’s mining sector, employing 500,000 people directly and supporting millions of people indirectly.

- Despite Nigeria’s vast mineral wealth, mining contributed only 4.38% to GDP in Q1 2025, down from 5.47% in 2024, due to ASM’s informality and weak oversight.

- Poor mining practices have led to serious public health crises causing 7,000 accidents and 700 deaths between 2010–2016 in Zamfara and Kebbi from mercury exposure and pit collapses.

- Regional Success Stories, such as in Ghana’s ASM gold output rose 70% in 2024, while Tanzania’s ASM employs 1.2 million people, contributes 22% of gold, and boosted mining’s GDP share to 10.1%.

- Initiatives like the Presidential Artisanal Gold Mining Initiative (PAGMI) launched in 2022, aim to formalize ASM through direct gold purchases. Broader reforms include decentralizing licensing, credit access, green technologies, stronger regulation, and gender inclusion.

INTRODUCTION

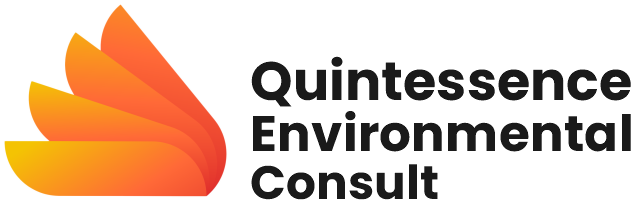

Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining (ASM) refers to low-tech, labor-intensive mineral extraction carried out by individuals, families, cooperatives, or small groups using simple tools and methods. It is usually informal or semi-formal, with little access to modern equipment, finance, or regulatory oversight. Globally, ASM employs 80–100 million people and constitutes up to 90% of the mining workforce, highlighting its significance in the global mining economy. In Nigeria, ASM sustains millions of livelihoods and makes up over 70% of the mining sector.

Artisanal mining in Nigeria has a history spanning more than 2,400 years [1]. Ancient communities such as the Nok, Kano, Benin, Ife, and Oyo extracted minerals like iron, clay, and gold as far back as 400 BC for sculpting and tool-making [1,2]. Today, although mining is often associated with multinational corporations investing billions of dollars and using heavy machinery, a quieter but equally significant ASM economy thrives. From the goldfields of Osun, Zamfara, and Niger to the tin deposits of Plateau, Bauchi, and Kano, and the gemstone markets of Kaduna, ASM provides livelihoods where farming or other jobs are limited.

However, this lifeline comes with paradoxes. While ASM reduces rural poverty, supports households, and contributes to mineral output, it is also plagued by informality, unsafe practices, environmental degradation, and lost government revenue. Nigeria faces a crucial choice: continue to allow ASM to operate in the shadows, or reform it into a pillar of sustainable livelihoods and responsible mining.

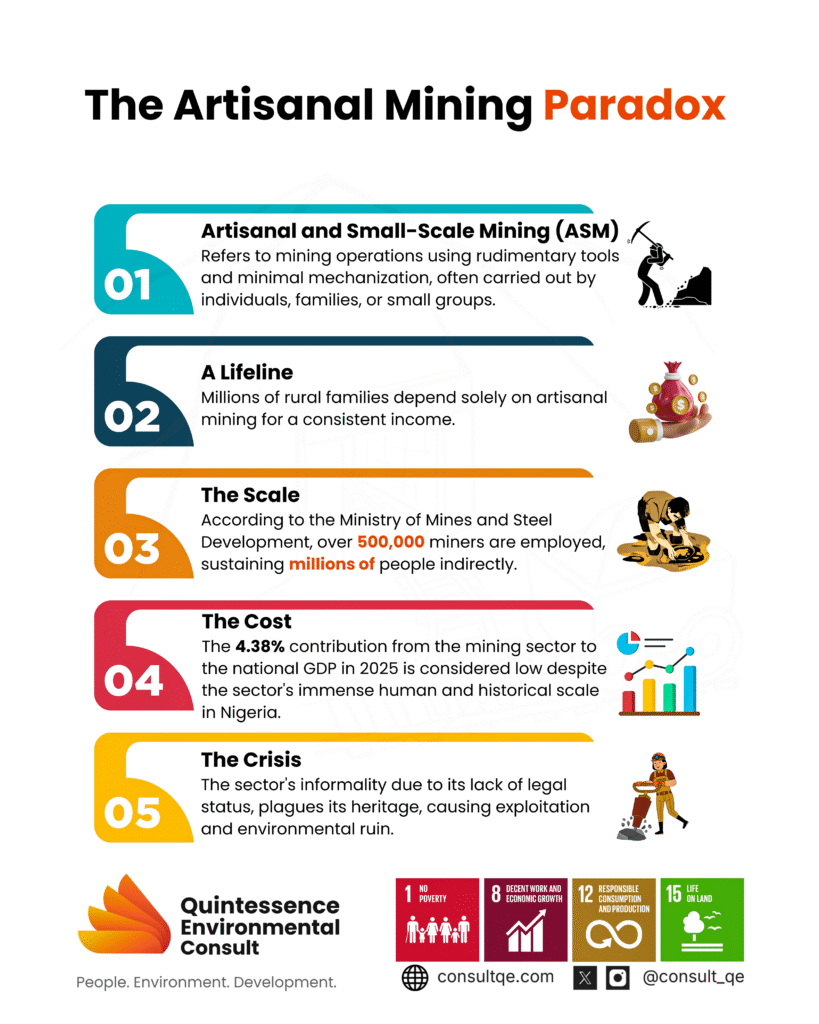

The sector remains underdeveloped despite Nigeria’s mineral wealth across more than 500 locations in the 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). The 4.38 Nigerian Mining Corporation, once a leading producer, declined after the 1970s indigenization policy, and now contributes 4.38 per cent to the overall GDP in the first quarter of 2025, lower than the 5.47 per cent contribution recorded in the same quarter of 2024, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) latest GDP report. [15] The underperformance stems largely from ASM-related challenges, including informality, weak regulatory oversight, insecurity, smuggling, and under-declaration of exported minerals.

HARNESSING NIGERIA’S ASM POTENTIAL FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

Nigeria is richly endowed with over 40 types of solid minerals, and ASM plays a vital role in their production. According to the Ministry of Mines and Steel Development, over 500,000 Nigerians are directly engaged in artisanal mining, and indirectly support millions in the sector through trade, transport, and processing.[13] For many rural households, ASM is not just an alternative; it is often the only dependable source of income when farming is disrupted by seasonal changes, land degradation, or insecurity.

Despite its potential, historical and structural challenges have hindered the sector. The discovery of oil in 1956, falling global metal prices, depletion of alluvial reserves, the Nigerian Civil War (1966–1970), and ineffective state operations all contributed to weakening mining development. The indigenization policy of the 1970s and subsequent mismanagement further eroded productivity. [3,2] Although attempts at reform, such as the World Bank’s $120 million Sustainable Management of Mineral Resources Project (2005), made progress in strengthening institutions like the Nigerian Geological Survey Agency and Mining Cadastral Office. Yet, the funds earmarked for ASM operators remain underutilized [3].Formalizing ASM by integrating its activities into the formal economy is crucial for unlocking its full potential. This requires comprehensive legal, regulatory, and policy frameworks to enhance government revenue, improve miners’ livelihoods, ensure safety, and minimize environmental harm. When properly organized, ASM can boost foreign exchange earnings, generate employment, support infrastructure development, and enhance sustainable livelihoods. Without reform, however, its benefits will remain stunted, and its risks overwhelming.[3, 4, 5, 6]

CASE STUDIES IN AFRICA

GHANA: Formalization, Market Reform & Export Growth

Ghana has recently recorded some of the most dramatic gains in its ASM sector thanks to reforms around licensing, exports, and market oversight. For example, in 2024, ASM gold production in Ghana rose by 70%, reaching ~1.9 million ounces compared to 1.1 million ounces in 2023. In that year, ASM miners contributed 39% of Ghana’s total gold output, up from 28% the year before. [7]

In early 2025, reforms led to ASM exporters exceeding the exports of large-scale miners. From February to May 2025, Ghana’s newly established Ghana Gold Board (GoldBod) exported 41.5 tonnes of gold from the ASM sector, valued at about US$4 billion, marking a historic first where small-scale miner exports overtook those from large-scale operations. [8]

Additional reforms include removing the 1.5% withholding tax on unprocessed small-scale gold, establishing transparent gold aggregation and buying centres, and introducing a traceability system. These changes helped reduce incentives for smuggling, improved prices for ASM producers, and boosted foreign exchange inflows. [9]

TANZANIA Zoning, Licensing & Contribution to GDP

Tanzania has also made substantive strides in recognizing and formalizing ASM through legal reforms, designated mining zones, and institution-building. Under legal transformations (Mining Acts, especially Cap 123 amended), Tanzania established 36 designated areas for small-scale mining operations covering over 280,000 hectares as of 2019. The ASM (artisanal and small-scale gold mining, ASGM) sub-sector directly employs more than 1.2 million people, representing about 3% of the national population, and over 90% of the mining labour force. Indirectly, ASM supports about 7.2 million additional livelihoods. ASM produces between 5.3 and 9.8 tonnes of gold per year, which translates to approximately 12-22% of Tanzania’s annual gold production in certain years. [10]

In 2024, the mining sector’s contribution to Tanzania’s GDP was reported at 10.1%, surpassing the government’s target ahead of schedule. Government stakeholders attribute the increase partly to reforms benefitting ASM: establishment of mineral markets and buying centres, crackdown on smuggling, improved licensing, and better regulatory oversight. [11]

CHALLENGES FACING ASM IN NIGERIA

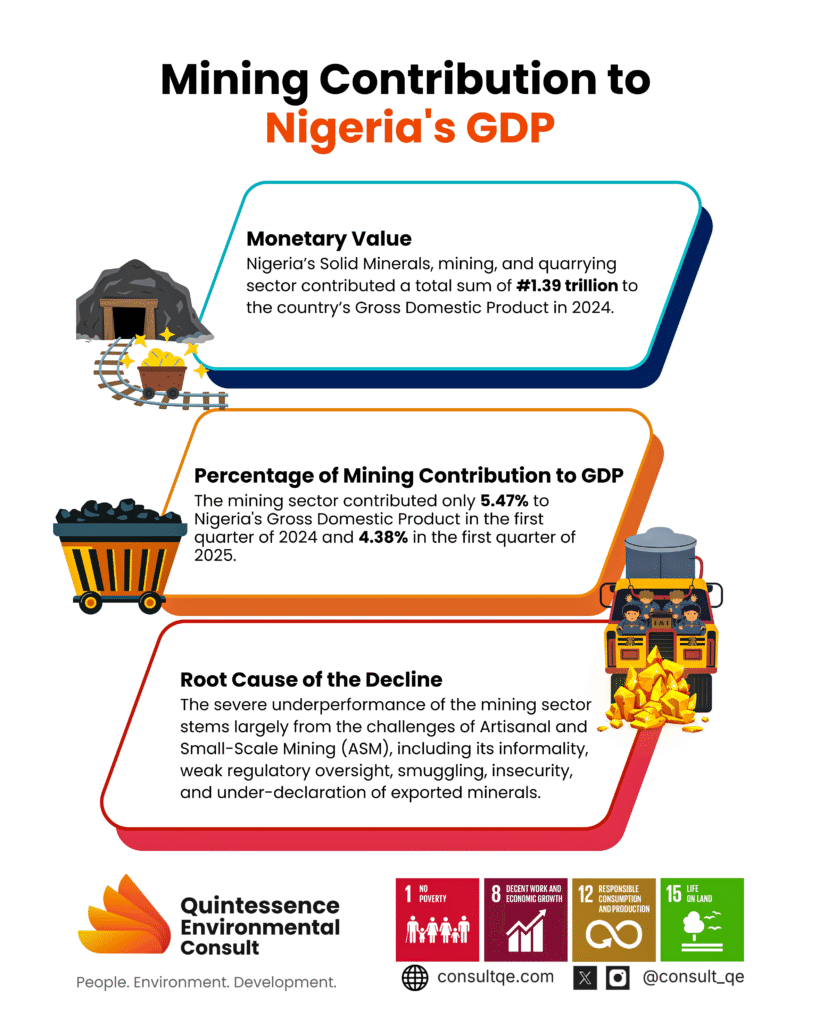

- Informality and Illegality: Most artisanal miners lack licenses due to the complex, costly, and centralized process. They operate without the legal mining titles required by the Nigerian Minerals and Mining Act, 2007, and the Minerals and Mining Regulations, 2011. This non-compliance results in the failure to pay mandatory royalties, with ASMs often resorting to financial inducements to community leaders and security personnel. Many of the ASM cooperatives only possess registration certificates from the ASM Department of the Ministry of Mines and Steel Development (MSMD), which are insufficient for legal operations without the required mineral titles from the Nigeria Mining Cadastre Office (MCO). This forces many into illegality, leaving them vulnerable to harassment and exploitation. For example, gemstone miners in Oyo and Nasarawa often sell tourmaline and aquamarine for far below their global value because Nigeria lacks lapidary centers and market structures.

- Environmental Degradation: ASM activities often cause deforestation, soil erosion, and water pollution. Unregulated kaolin pits in Katsina have scarred farmlands, while clay extraction in Ekiti, though supporting pottery, has degraded land without reclamation.

- Health and Safety Risks: Collapsing pits often cause fatalities, while long-term exposure to dust leads to silicosis and tuberculosis. Use of mercury in gold processing causes kidney, nerve, and brain damage, with symptoms such as tremors and memory loss. Unsafe gold mining has caused more than 7000 accidents and 700 deaths from 2010 to 2016 in Zamfara and Kebbi states. This tragedy shows how poor safety in ASM can devastate entire communities. [14]

- Economic Inefficiency: With rudimentary tools like pans and shovels, miners recover only a fraction of available minerals. Middlemen exploit them by buying cheaply and selling at global market rates, trapping miners in poverty despite their hard labor.

- Social Concerns: ASM sites often host child labor, with children carrying loads or processing minerals instead of attending school. In some areas, illegal mining has been linked to funding armed groups, while disputes over land rights fuel conflicts with host communities.

- Gender and Youth Exclusion: Women and youth form a large portion of Nigeria’s ASM workforce, particularly in mineral processing and trading. Yet, they often face discrimination, poor wages, and limited access to licenses, credit, and decision-making structures. Without deliberate gender- and youth-sensitive reforms, a major share of the workforce will remain marginalized, weakening the sector’s contribution to inclusive development.

A PATH TO REFORM

Reforming ASM does not mean shutting it down. Rather, it means harnessing its potential while minimizing its harms. Nigeria is on the path to reforming its ASM sector through the Presidential Artisanal Gold Mining Initiative (PAGMI), launched in 2022 and led by NSIA (Nigerian Sovereign Investment Authority) in collaboration with the Presidency, the Solid Minerals Development Fund, and the Ministry of Mines and Steel. This initiative aims to formalize Nigeria’s artisanal and small-scale gold mining sector by purchasing gold directly from miners, refining it to export standard, and selling it at competitive international rates. By doing so, PAGMI seeks to reduce illicit mining, enhance revenues for the government, ensure fair treatment of miners, and generate sustainable value for Nigeria’s economy.[12]

However, Nigeria can also learn from countries like Ghana and Tanzania, which have made strides in formalizing ASM. Further recommendations for this reform are as follows:

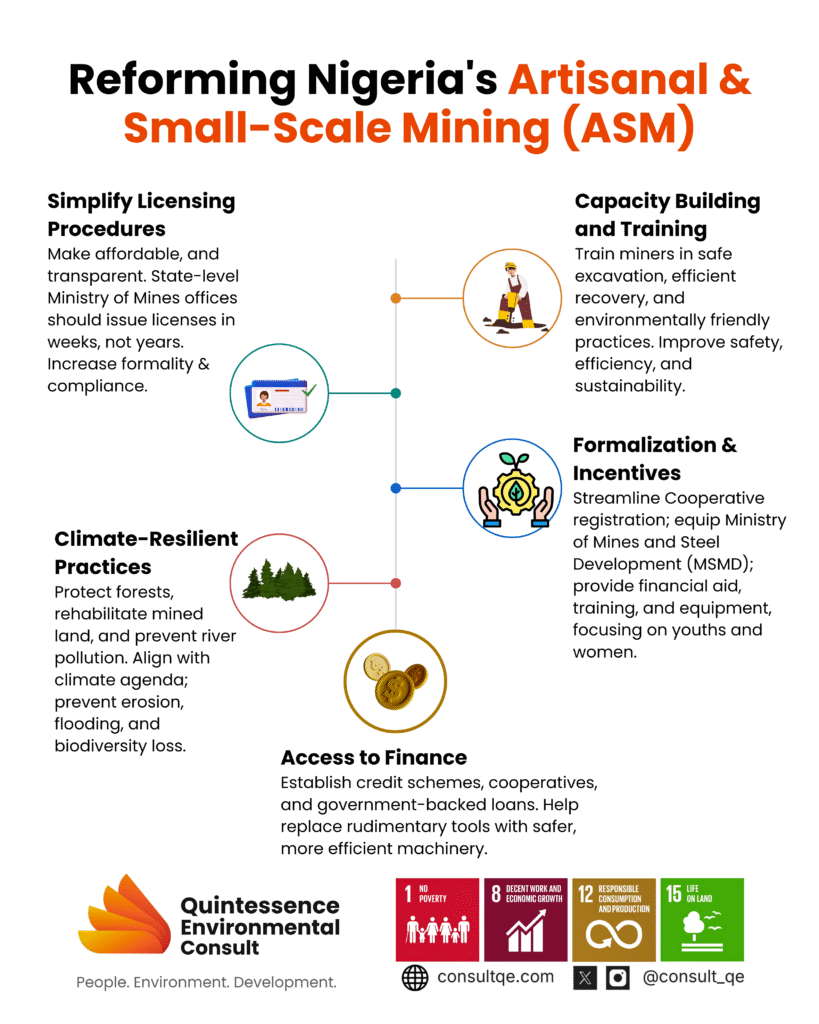

- Simplify Licensing and Support Formalization: Simplifying and decentralizing the licensing process is essential for ASM reform. Licensing should be affordable, transparent, and processed within weeks rather than years, while the ASM Department of the Ministry of Mines and Steel Development (MMSD) must be adequately staffed and equipped to carry out its oversight functions. Registration of ASM cooperatives should be streamlined to reduce delays and bureaucratic bottlenecks. Pilot formalization initiatives should also be implemented and assessed to refine the process before scaling, ensuring that miners transition from informality into regulated operations effectively.

- Enhance Capacity, Finance, and Innovatio: To address the financial and technical gaps in ASM, Nigeria should provide credit schemes, cooperative loans, and government-backed financing, particularly targeting women and youth. Equipment leasing programs and shared machinery facilities would give miners access to modern, safer tools, while regular training should be provided in safe mining methods, efficient mineral recovery, and environmentally friendly practices. Encouraging the use of green technologies, such as mercury-free gold extraction and portable processing plants, will reduce environmental and health risks. Meanwhile, technological innovations like blockchain for mineral traceability, drones for monitoring illegal pits, and mobile platforms for licensing and trade can modernize the sector and expand fair market access.

- Promote Environmental and Climate-Resilient Mining: ASM reforms must integrate strict environmental protection protocols to reduce deforestation, erosion, and water pollution. Rehabilitating mined-out areas through reforestation and soil restoration will help restore ecosystems and farmland. Aligning ASM operations with Nigeria’s broader climate adaptation agenda is crucial to preventing flooding, biodiversity loss, and other climate-related risks. Local communities should also be engaged in developing environmental safeguards and infrastructure projects to promote sustainable practices and ensure long-term resilience.

- Advance Social Inclusion and Gender Equality: Promoting gender and youth inclusion in ASM is critical for equitable growth. Women should be guaranteed equal pay for equal work, given access to property ownership rights, and supported in obtaining licenses and financial credit. Encouraging the formation of women’s unions and cooperatives will strengthen their bargaining power and welfare. Dedicated mentoring and leadership training should be offered to women and youth to improve their opportunities for growth in the sector. Safeguards must also be established to address gender-based violence at mining sites, while childcare and family support systems should be introduced to improve working conditions for women miners.

- Strengthen Community Development and Awareness: For ASM to deliver sustainable benefits, mining revenues must be reinvested into local development projects, including schools, clinics, and rural infrastructure. Continuous advocacy and sensitization programs should be carried out in collaboration with local government councils to educate miners on regulations, the benefits of formalization, and best safety practices. Strengthening MSMD’s extension services will further ensure that miners have access to credible information, timely support, and channels for feedback, thereby building trust between operators and government institutions.

WHY REFORM MATTERS FOR NIGERIA

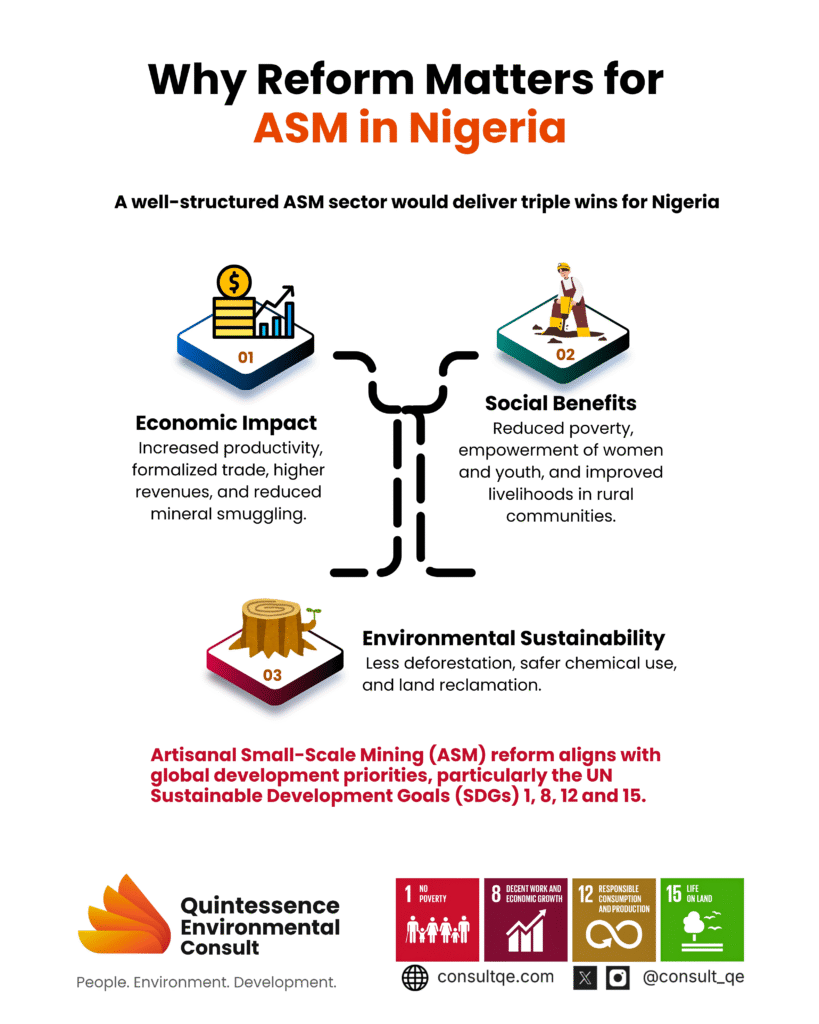

A well-structured ASM sector would deliver triple wins for Nigeria:

- Economic Impact: Increased productivity, formalized trade, higher revenues, and reduced mineral smuggling.

- Social Benefits: Reduced poverty, empowerment of women and youth, and improved livelihoods in rural communities.

- Environmental Sustainability: Less deforestation, safer chemical use, and land reclamation.

Moreover, ASM reform aligns with global development priorities, particularly the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):

- SDG 1 (No Poverty) through livelihood support,

- SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) through safer, more productive jobs,

- SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) through formalized mineral value chains, and

- SDG 15 (Life on Land) through land reclamation and biodiversity protection.

CONCLUSION

Nigeria stands at a crossroads. Long dismissed as informal or illegal, ASM can become a cornerstone of sustainable development if the right reforms are pursued. By prioritizing simplified licensing, improved market structures, gender inclusion, and green technologies, ASM can transition into a formalized, productive, and sustainable sector. If Nigeria harnesses its ASM potential, it can deliver significant economic growth, reduce rural poverty, and align with global sustainability goals such as the SDGs, while also strengthening national security and environmental resilience.

REFERENCES

[1] Jemkur, J.F., Chesi, G., Merzeder, G., and Rasmussen, M., 2006. The Nok Culture: Art in Nigeria 2500 years ago, Prestel Publication.

[2] Ministry of Mines and Steel Development (MMSD), 2008. National Baseline Study on the Development of Artisanal Small Scale Mining in Nigeria. Draft report presented to the Ministry of Mines and Steel Development of the Federal Government of Nigeria by Kevin D’Sousa.

[3] Michelou, J.C., 2006. Baseline Study of the Nigerian Gemstone Industry Development. A report prepared for the Ministry of Solid Minerals Development, Federal Republic of Nigeria.

[4] Labonne, B., 2002. Commentary: Harnessing Mining for Poverty Reduction, Especially in Africa: Natural Resources Forum, v. 26, p. 69–73.

[5] Pegg, S., 2006. Mining and poverty reduction: Transforming rhetoric into reality: Journal of Cleaner Production, v. 14, p. 376–387.

[6] Hayes, K., 2008. Artisanal & Small-scale Mining & Livelihoods in Africa. Paper prepared for an international seminar titled: “Small-scale Mining in Africa – A Case for Sustainable Livelihood” Prior to the opening of the 20th Annual Meeting of the Governing Council of the Common Fund for Commodities 25-26 November, at the Zanzibar Beach Resort, Zanzibar, Tanzania.

[7] Ecofin Agency, 2024 Ghana’s Small-Scale gold output rises 70% in 2024. https://www.ecofinagency.com/news-industry/0206-47097-ghana-s-small-scale-gold-output-rises-70-in-2024?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[8] GoldBod exports 41.5 tonnes of ASM gold worth US$4 billion in four months – Ghana Gold Board. (2025, June 3). https://goldbod.gov.gh/goldbod-exports-41-5-tonnes-of-asm-gold-worth-us4-billion-in-four-months/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[9] Ali, M. (2025, September 10). Small-scale gold exports hit record US$6.3 billion in 8 months, surpass 2024 total. Graphic Online. https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/small-scale-gold-exports-hit-record-66-7-tonnes-in-8-months-surpass-2024-total.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[10] SCOPING STUDY FOR THE PERFORMANCE OF TANZANIA EXTRACTIVE INDUSTRIES AND PREPARATION OF 12TH TEITI REPORT FOR THE FISCAL YEAR 2019/2020

[11] Reporter, C. 2025. Mining beats 10 percent GDP target a year earlier. The Citizen. https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/news/national/mining-beats-10-percent-gdp-target-a-year-earlier-5014564?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[12] Nigeria Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA). (2025). Presidential Artisanal Gold Mining Initiative (PAGMI). Online: https://nsia.com.ng/portfolio/presidential-artisanal-gold-mining-initiative-pagmi/

[13] Tunji, T. (2025) Artisanal Mining in Nigeria: Bridging the Gap Between Informality and Investment. verivAfrica, 7 July. Available at: https://www.verivafrica.com/insights/artisanal-mining-in-nigeria-bridging-the-gap-between-informality-and-investment

[14] BBC News Pidgin. (2020, July 16). Gold mining: How PAGMI, Nigeria Presidential Artisanal Gold Mining Development Initiative go work and benefit you. online: https://www.bbc.com/pidgin/tori-53436915

[15] Premium Times Nigeria. (2025, July 22). Mining, quarrying sector’s contribution to GDP drops in Q1 2025. Online: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/business/business-news/808749-mining-quarrying-sectors-contribution-to-gdp-drops-in-q1-2025.html