KEY TAKEAWAYs:

- Nature-based Solutions (NbS) are highly adaptable to Nigeria’s diverse regional challenges.

- The primary barrier to scaling NbS is financing, which can be overcome by adopting a business model approach.

- Financial sustainability for NbS projects depends on “stacking” multiple revenue streams.

- Investing in nature is a strategic economic opportunity for Nigeria, not just an environmental cost.

- Key policy asks include incentivizing private sector investments, establishing a national NbS fund, establishing a robust MRV for quality assurance and facilitating capacity building and knowledge sharing on NbS business models.

- INTRODUCTION

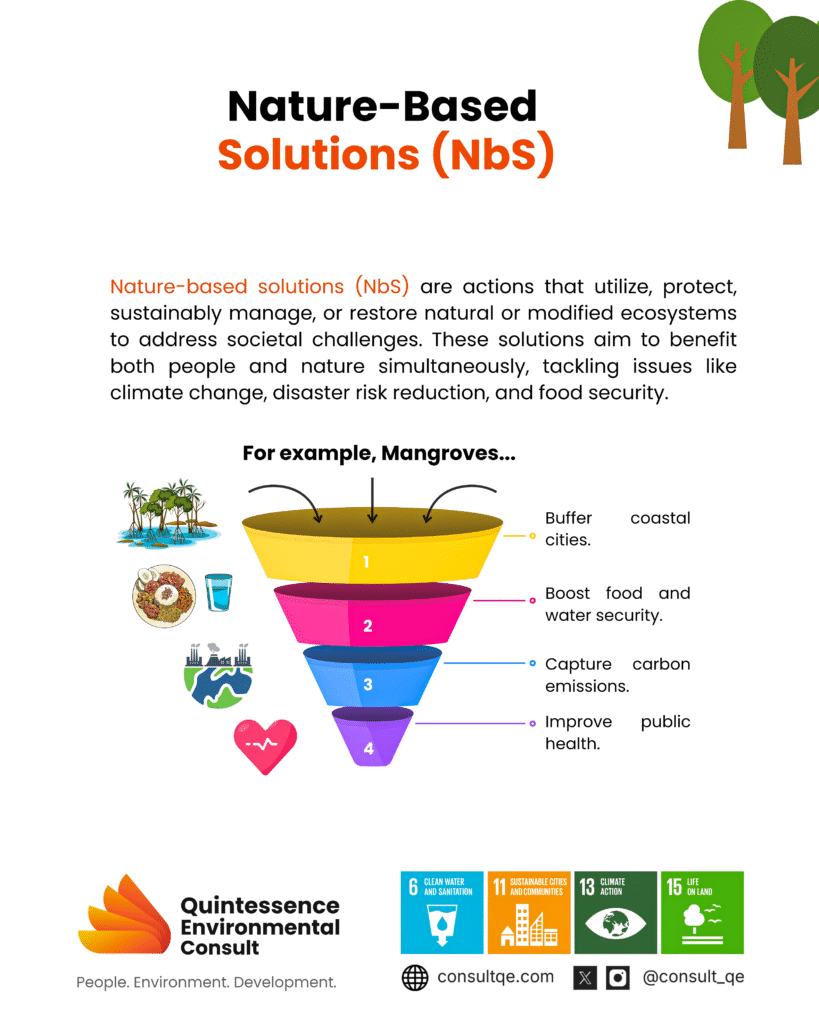

From the submerged streets of Victoria Island during a downpour to the blistering, sun-baked landscapes of the Sahelian north, Nigeria is on the front lines of a climate crisis. So far, rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and increased frequency of flooding have disrupted many lives and exacerbated existing vulnerabilities and conflicts, jeopardizing the country’s socio-economic stability.

In particular, the frequency of floods in Nigeria has increased by more than 25%1 leading to loss of lives, properties, farmlands and increased conflicts. Nigeria suffered an estimated loss of $16.9 billion in damaged properties, oil production, agriculture and others due to flood events in 2012 alone.2 Similarly, over 80,000 were affected by floods across Nigeria in the following year of 2013. Furthermore, Kogi, Kebbi, Anambra, Delta and Edo States experienced some of the worst flooding incidents, which affected 500,000 people in the States.

In 2022, the UN-Displacement Tracking Matrix reported a total of 37,475 individuals (16,393 in Borno State, 5,979 in Adamawa State and 15,042 in Yobe State) were affected by heavy rainfalls that led to flooding since the inception of the rainy season. In September 2024, flood waters from the Alau Dam of Borno State devastated Maiduguri metropolis and adjoining areas where over 1.5 million people were displaced, and economic activities were crippled.

For example, the 2022 floods in the Guri and Kirikasamma council areas of Jigawa have reduced fertile land, worsening the clashes. Children have been disproportionately affected by the impacts of farmer-herder violence. Clashes have made families flee their homes and lose their livelihoods, in turn increasing safety concerns, dwindling vital resources and infrastructure, and upending access to social support and education for children.3

In terms of desertification and biodiversity loss, the United Nations reports Nigeria as having the highest rate of deforestation in the world, losing 3.7% of its forest every year.4 Accordingly, wildlife and vast ecosystems across Nigeria’s rich ecological zones are under severe threat. Similarly, the changing landscape and freshwater supplies have forced pastoralists to migrate southward across tribal and sub-national boundaries, worsening the conflicts between them and farmers whose lands are being encroached upon.

The nation’s response has been etched in concrete and steel: higher seawalls, wider drainage channels, and temperature control solutions that rely on non-renewable energy sources. But a growing body of evidence suggests a more resilient, cost-effective, and powerful ally in this fight has been overlooked: nature itself.

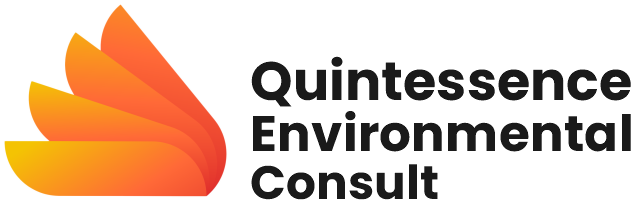

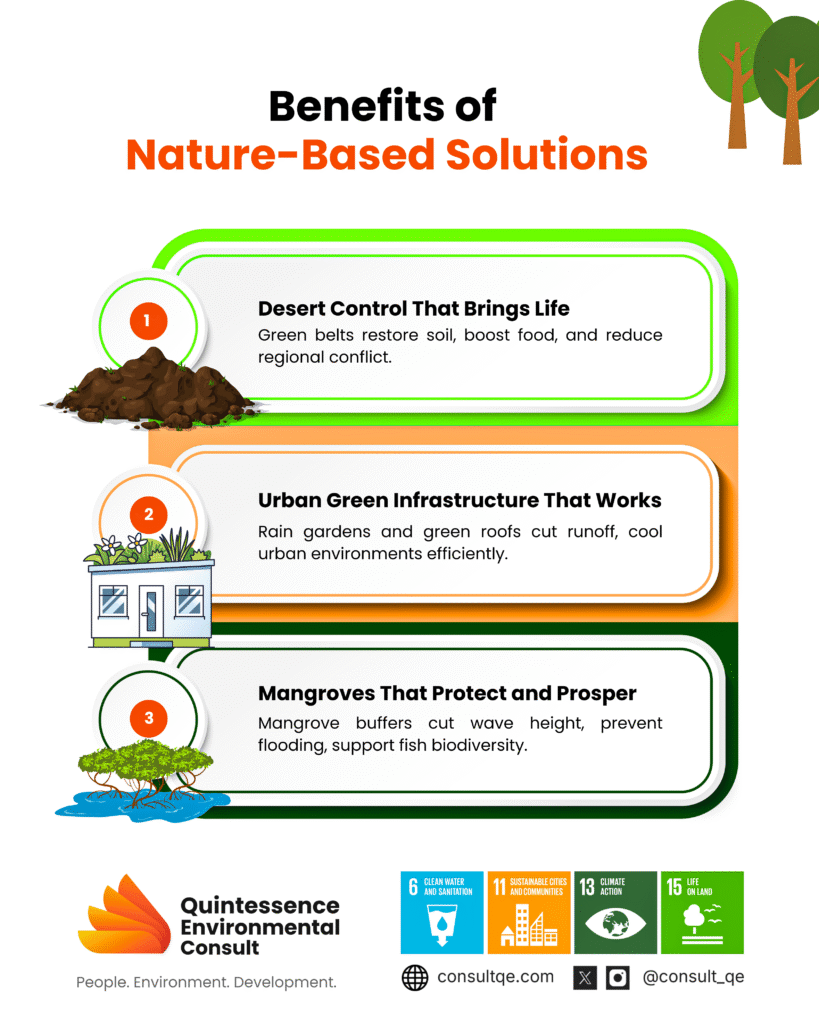

Nature-based Solutions (NbS) are actions that harness the power of healthy ecosystems to tackle our most pressing societal challenges. This isn’t about simply planting trees; it’s a strategic approach to weave natural systems back into our urban and rural landscapes to defend against climate change, create economic value, and improve the quality of life for millions. While the potential is immense, the path to implementation has been blocked by a critical hurdle: financing. The solution, it turns out, is to stop thinking of NbS as charity projects and start building them as bankable, profitable business models.5

2. A BLUEPRINT FOR EVERY REGION

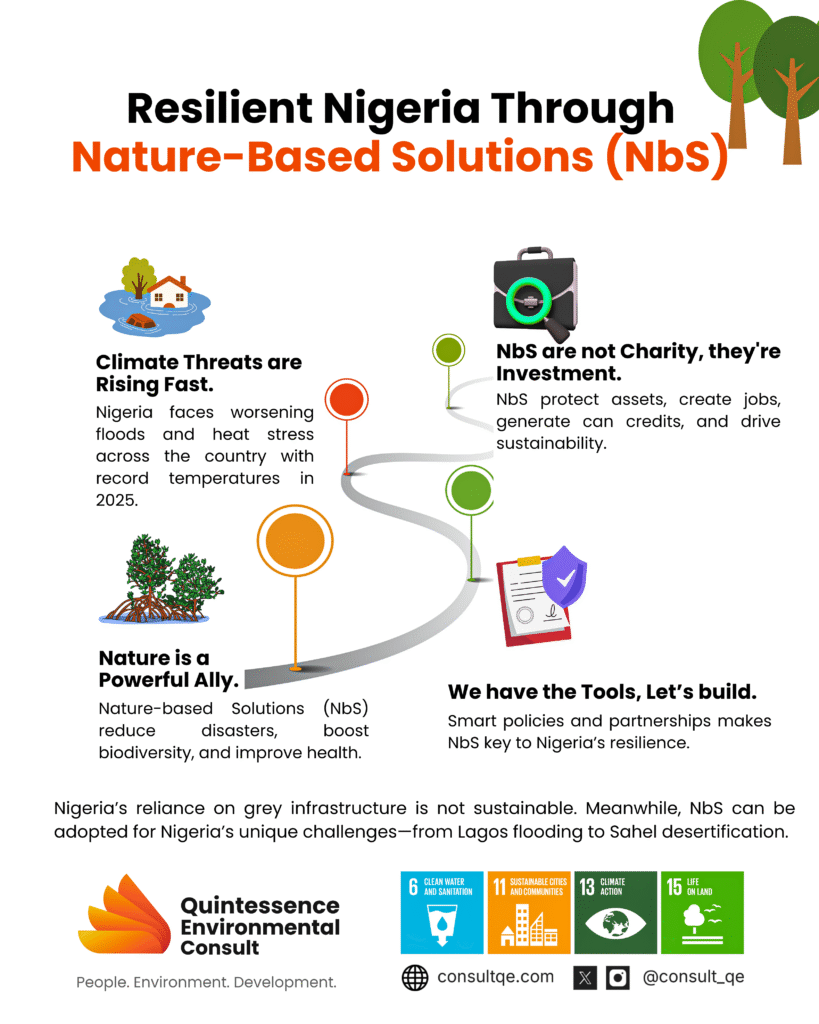

Nigeria’s diverse geography demands tailored solutions. What works for the coastal creeks of the Niger Delta will not solve the desert encroachment in Sokoto. The beauty of NbS lies in its adaptability.

2.1 Taming the Tides: Coastal Management in the South

In coastal states like Bayelsa, Rivers, and Lagos, rising sea levels and storm surges are an existential threat. The traditional response of building hard concrete walls is expensive and often just moves the problem elsewhere.

2.1.1.The Solution: Mangrove Restoration.

Mangrove forests are nature’s perfect coastal engineers. Their dense root systems act as a natural buffer, dissipating the energy of waves and trapping sediment to stabilize shorelines. A healthy 500-meter-wide mangrove forest can reduce wave height by 50-100%6. Beyond protection, they are critical breeding grounds for fish and crustaceans, supporting local livelihoods, and are carbon sequestration powerhouses.

2.2 Quenching Thirsty Cities: Tackling Urban Flooding

For residents of Lagos, Port Harcourt, and Ibadan, perennial flooding is a grim reality. Decades of paving over natural floodplains and green spaces have left rainwater with nowhere to go, overwhelming concrete drainage systems.

2.2.1 The Solution: Green Urban Infrastructure.

This involves a suite of interventions designed to mimic natural water cycles.

A. Rain gardens and vegetated swales are shallow, landscaped depressions that collect rainwater, filtering it and allowing it to soak into the ground.

B. Permeable pavements in parking lots and walkways allow water to pass through the surface into the ground instead of running off.

C. Urban floodplain restoration involves reclaiming and revitalizing natural channels to store and manage excess water. Studies show that such measures are highly effective; retention ponds and swales can reduce peak stormwater discharge by over 40%.7

2.3 Cooling the Concrete Jungles: Combating Urban Heat

As cities like Abuja and Kano expand, vast expanses of asphalt and concrete absorb and radiate heat, creating “urban heat islands” where temperatures are significantly higher than in surrounding rural areas.

2.3.1 The Solution: Strategic Urban Greening.

A. Urban parks and street trees provide shade and release moisture through evapotranspiration, creating cooling effects.

B. Green buildings, featuring green roofs and walls, are particularly effective. A vegetative layer on a roof insulates the building, leading to energy savings of up to 25-35% on cooling needs. This directly reduces reliance on air conditioning, lowering energy bills and carbon emissions.

2.4 Holding Back the Sands: Reversing Desert Encroachment

In the arid North, the Sahara Desert advances southward each year, degrading farmland and threatening the livelihoods of millions.

2.4.1 The Solution: Urban and Peri-Urban Forestry.

The strategic planting and conservation of forests and green belts on the peripheries of cities and villages can be a powerful defence. These woodlands improve soil health, increase water retention, and create essential microclimates that can support agriculture. They also provide communities with sustainable sources of wood, food, and other forest products.

2.5 Successful Implementation of Nature-based Solutions Around the World

Nature-based solutions (NbS) are increasingly recognized as powerful tools to address global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, and disaster risk. One prominent example is the widespread restoration and protection of mangrove forests in coastal regions. Countries like Jamaica, Colombia, and the Philippines have invested in these efforts, leveraging mangroves’ natural ability to dissipate wave energy, prevent erosion, and act as significant carbon sinks. Beyond coastal protection, these restored ecosystems provide vital nursery grounds for fish, supporting local livelihoods and food security8.

In urban settings, green infrastructure like green roofs, rain gardens, and restored urban wetlands has proven highly effective. Cities such as Basel, Switzerland, have implemented extensive green roof programs that help reduce the urban heat island effect, manage stormwater runoff, and enhance local biodiversity. Similarly, the restoration of urban wetlands in places like Colombo, Sri Lanka, has significantly reduced flood risk for residents while improving water quality and creating valuable public green spaces. 9,10,11

Furthermore, reforestation and sustainable forest management projects are crucial for climate mitigation and adaptation. Initiatives like the Great Green Wall in Africa’s Sahel region aim to combat desertification and improve livelihoods through large-scale tree planting. In Colombia, investments in silvopastoral systems are helping reduce emissions from livestock farming while maintaining farmer incomes and restoring degraded landscapes. These examples highlight how NbS offer integrated solutions, delivering multiple co-benefits beyond their primary objective. 12,13,14

3. FROM IDEA TO INVESTMENT: CREATING BANKABLE PROJECTS

The primary reason these solutions haven’t been implemented at scale is the perception that they are difficult to finance. The UNEP-CCC’s “Business Models for Financing Nature-based Solutions” guide provides a clear roadmap to overcome this, transforming environmental projects into investment-ready enterprises. The core idea is to build a compelling business case that attracts both public and private capital.

Here is a practical strategy for creating a bankable NbS project in Nigeria:

Step 1: Define Your Value Proposition (The “Why”)

A bankable project starts with a clear articulation of the value it creates—not just ecologically, but financially and socially. Move beyond vague statements like “improving biodiversity” to quantifiable metrics.

A. Bad Pitch: “We want to plant mangroves to help the environment.”

B. Bankable Pitch: “Our mangrove restoration project in the Niger Delta will protect USD 50 million in coastal infrastructure from storm surges, increase local fishery yields by 30% within five years, create 200 direct jobs, and sequester 15,000 tonnes of CO2 annually, generating revenue from carbon credits.”

Step 2: Identify Your Beneficiaries and Partners (The “Who”)

Who benefits from your project? The answer to this question is your key to identifying partners and revenue streams. A successful NbS project is a coalition effort.

A. Beneficiaries: These can include homeowners protected from floods, businesses with lower insurance premiums, utility companies that get cleaner water, and the entire community enjoying better health and recreational spaces.

B. Partners: Engage a wide range of actors. This includes government agencies for permits and policy support, private companies for investment and technical expertise, and community groups to ensure local ownership and long-term sustainability.

Step 3: Map Your Costs and Revenue Streams (The “How”)

This is where the business model truly takes shape. A project must have a clear understanding of its costs and a diverse plan for generating income to cover them.

A. Costs: Be realistic about both the upfront Capital Expenditures (CAPEX) for design, land, and construction, and the long-term Operational Expenditures (OPEX) for maintenance and monitoring.

B. Revenue Streams (The Multi-Layered Approach): Relying on a single source of funding is risky. The most successful models “stack” multiple revenue streams:

- Public Funding: This is the foundational layer. Seek government budgets, grants, subsidies, or tax incentives designed to promote environmental goals. Also, target international funds like the Green Climate Fund (GCF).

- Corporate Investment: Approach private companies that directly benefit. A real estate developer could invest in green infrastructure to increase property values and reduce flood risk for their developments.

- Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES): This is a direct, market-based mechanism21. For instance, a manufacturing company that relies on clean water could pay an upstream community to maintain a forested watershed that naturally filters its water supply.

- Carbon and Biodiversity Credits: Projects that verifiably sequester carbon (like urban forests) or restore biodiversity can sell these credits on voluntary markets to corporations looking to meet their climate and nature-positive commitments.

- Innovative Finance: For large-scale projects, explore advanced mechanisms:

C. Sustainability Bonds: A state government or a large city could issue a “Green Bond” to raise millions of dollars from institutional investors to finance a massive NbS infrastructure program, such as overhauling Lagos’s water management system.

D. Blended Finance: This is crucial for attracting risk-averse private investors. It involves using public or philanthropic money as a guarantee or first-loss capital, making it safer for commercial banks to lend to an NbS project.

E. Community Financing: For smaller, local projects, crowdfunding and community donations can be a powerful tool for raising initial capital and ensuring community buy-in.

4. A Vision for a Nature-Positive Nigeria

The climate challenge facing Nigeria is immense, but so is the opportunity. Nature-based Solutions offer a path to not only adapt and mitigate the impacts of climate change but also to build a more just, healthy, and prosperous nation.

The shift requires a new way of thinking. Policymakers should adopt the best of programs like the ACReSAL, the Great Green Wall Initiative, and REDD+ to foster the regulatory environment. In addition, the Climate Change ACT of 2021 should be wielded across the federal and subnational levels to ensure the adoption of nature-based solutions for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Meanwhile, entrepreneurs, community leaders, and innovators should step up to design and develop these bankable business models.

Some key considerations for policymakers are relevant and presented as follows:

- Establish a dedicated national NbS investment fund which can be a dedicated, multi-stakeholder national fund specifically for NbS projects. This fund could be capitalized through a combination of public allocations (from national budget, potentially carbon tax revenues), international climate finance mechanisms (e.g., Green Climate Fund, Adaptation Fund), private sector contributions (e.g., impact investors, corporate social responsibility initiatives), and innovative financing instruments (e.g., green bonds, debt-for-nature swaps). This provides a clear, centralized mechanism for channeling finance to NbS projects, reducing fragmentation and increasing efficiency. It signals a strong government commitment and provides a platform for attracting diverse forms of capital.

- Develop a robust national NbS monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) Framework with Economic Valuation, including standardized methodologies for quantifying carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation, water regulation, and other ecosystem services. Crucially, this framework should incorporate economic valuation of these benefits. This can attract private investment and promote results-based financing because economic valuation helps to quantify the financial benefits (e.g., avoided losses, increased productivity) and makes a stronger business case for investment beyond purely environmental returns. It can also enable the development of robust carbon markets and other payment for ecosystem services schemes.

- Incentivize private sector engagement through financial mechanisms and regulatory support by introducing targeted financial incentives for businesses and entrepreneurs engaging in NbS, such as tax breaks, preferential loan rates, grants for pilot projects, and risk-sharing mechanisms. Simultaneously, streamline regulatory processes and provide clear guidelines for NbS project development and implementation. Explore “green procurement” policies for government contracts.

- Strengthen capacity building and knowledge sharing on NbS finance for government officials, financial institutions, local communities, and project developers. Other aspects include NbS design, implementation, and most importantly, financial structuring. This includes training on accessing international climate finance, developing bankable proposals, and understanding carbon markets and other innovative finance mechanisms.

Overall, investing in nature is not an expense; it is the most critical economic, social, and environmental investment Nigeria can make in its own future. The blueprint is here. It’s time to build.

REFERENCES

- Nura Umar and Alison Gray, 2003. Flooding in Nigeria: a review of its occurrence and impacts and approaches to modelling flood data. International Journal of Environmental Studies 2023, VOL. 80, NO. 3, 540–561 https://doi.org/10.1080/00207233.2022.2081471

- Egbenta, I.R., Udo, G.O. & Otegbulu, A.C., Using hedonic price model to estimate effects of flood on real property value in Lokoja Nigeria. Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management, 8(5), pp. 507–516, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ejesm.v8i5.4

- UN Migration (IOM): Climate Change, Disasters, Insecurity, and Displacement: The Impact of Flooding on Youth Marginalization and Human Mobility in Nigeria. https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/blogs/climate-change-disasters-insecurity-and-displacement-impact-flooding-youth-marginalization-and-human-mobility-nigeria

- United States International Development Agency (USAID): Nigeria Climate Change Country Profile. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-11/2023-USAID-Nigeria-Climate-Change-Profile.pdf

- United Nations Environment Programme Copenhagen Climate Centre (UNEP-CCC). 2024. Business Models for Financing Nature-based Solutions in Urban Climate Action: A Knowledge Resource for Cities in Developing Countries. Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Reshma Sunkur, Komali Kantamaneni, Chandradeo Bokhoree, Shirish Ravan (2023). Mangroves’ role in supporting ecosystem-based techniques to reduce disaster risk and adapt to climate change: A review. Journal of Sea Research Vol. 196.

- Kõiv-Vainik, M., Keit Kill, K.. Espenberg, M., Uuemaa, E., Teemusk, A., Maddison, M., et al. (2022). Urban stormwater retention capacity of nature-based solutions at different climatic conditions. Nature-Based Solutions, 2, 100038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbsj.2022.100038

- Mangrove restoration as a nature-based solution in biosphere reserves in Latin America and the Caribbean (UNESCO Report). https://www.unesco.org/en/mab/mangres#:~:text=By%20restoring%20and%20conserving%20mangroves,services%20provided%20by%20mangroves%20through

- US EPA Report: Using Green Roofs to Reduce Heat Islands. https://www.epa.gov/heatislands/using-green-roofs-reduce-heat-islands

- Basel, Switzerland: Green roofs : Combining mitigation and adaptation on measures (OPPLA). https://oppla.eu/casestudy/18381#:~:text=A%20comprehensive%20suite%20of%20mechanisms,of%20green%20roofs%20in%20Basel.

- Once used as trash dumps, Sri Lanka’s wetlands are remade as flood-buffering parks (Bulletin of the Atomic Scientist). https://thebulletin.org/2024/06/once-used-as-trash-dumps-sri-lankas-wetlands-are-remade-as-flood-buffering-parks/

- USDA Forest Service: https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/forest-management/vegetation-management/reforestation

- UNCCD: Great Green Wall Initiative. https://www.unccd.int/our-work/ggwi

- Silvopastoral systems for enhanced productivity, environmental sustainability and rural development (FAO). https://www.fao.org/nr/sustainability/foro-electronico/proyectos/projects-detail/es/c/216258/