KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Microplastics, originating from both primary (e.g., microbeads) and secondary (e.g., degraded plastics) sources, are pervasive in the environment. They enter the human body through ingestion, inhalation, and dermal absorption, accumulating in organs such as the liver, lungs, and brain.

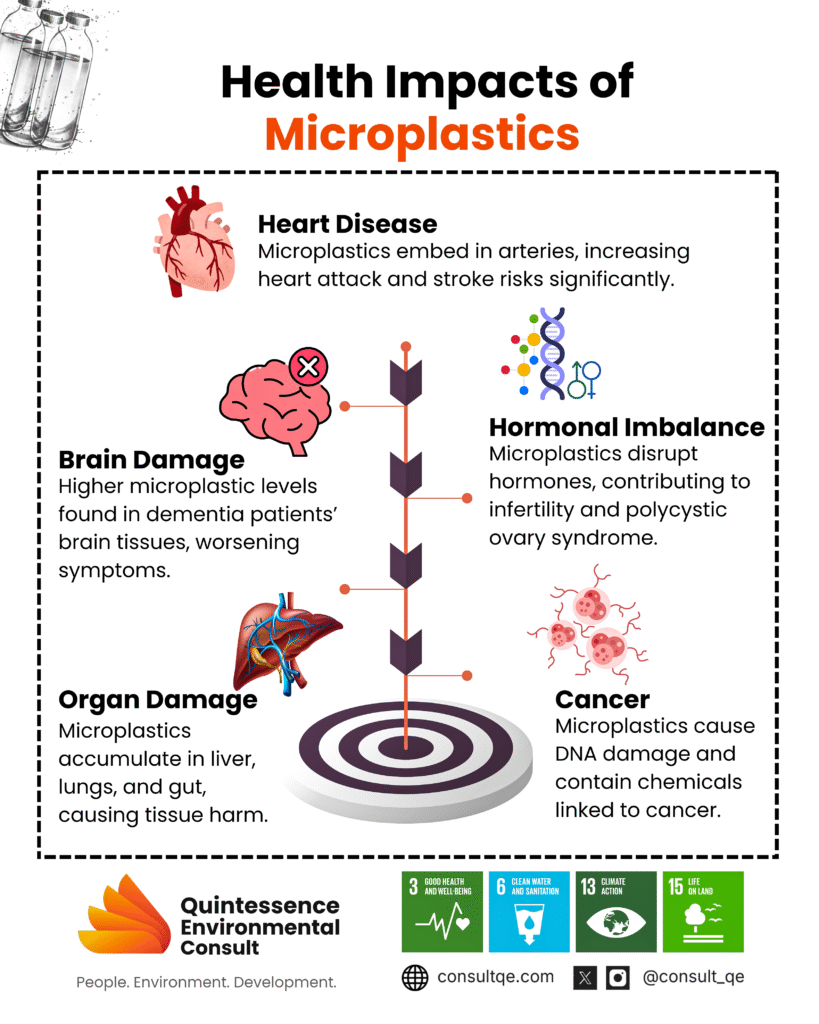

- Exposure to microplastics is linked to various health issues, including cardiovascular diseases, neurological disorders, hormonal imbalances, organ damage, and cancer.

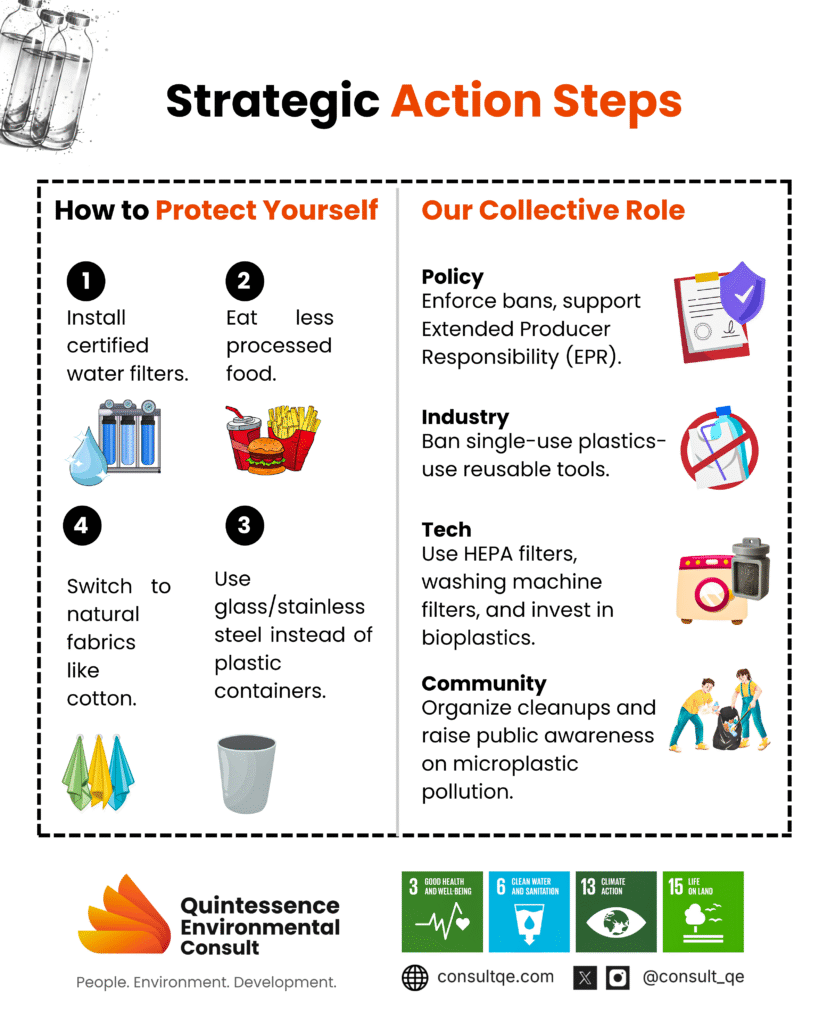

- Reducing microplastic exposure involves (e.g., using glass containers, filtering water), community initiatives (e.g., cleanups, public education), and policy measures (e.g., bans on single-use plastics, Extended Producer Responsibility programs).

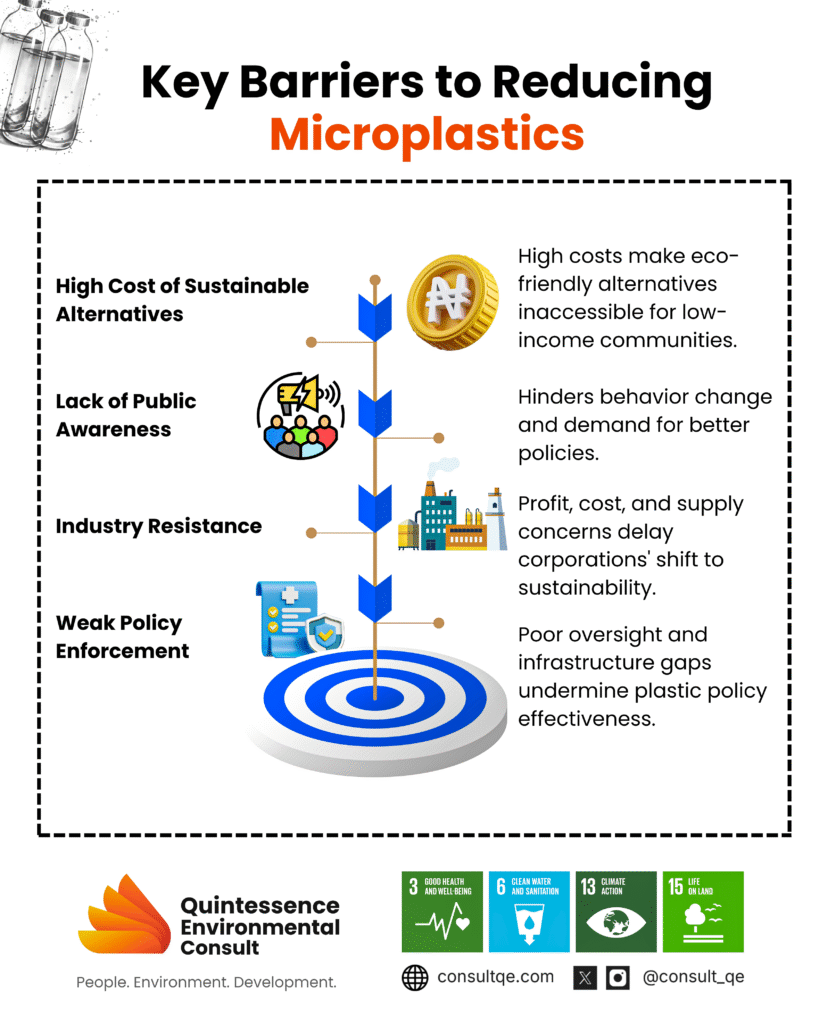

- Efforts to mitigate microplastic pollution face obstacles such as higher costs of sustainable alternatives, lack of public awareness, resistance from industries, and inadequate policy enforcement.

- Given the widespread presence of microplastics and their potential health impacts, there is an urgent need for coordinated global efforts involving individual actions, industry innovation, and stringent policy implementation to protect human health and the environment.

INTRODUCTION

Microplastics have infiltrated the Earth’s ecosystem. They have been found in the air we breathe, in soils that grow our food, and in the oceans that sustain life. But the most recent alarming infiltration is the human body. Recent studies reveal that these particles are now lodged in our blood, organs, and even our brains, raising urgent questions about their long-term health impacts. The discovery of plastic in such intimate spaces has triggered global alarm, forcing scientists and policymakers to confront an unsettling question: What happens when an artificial material, designed to last centuries, becomes a permanent resident in our bodies? Microplastics are now unmasked as a silent, creeping threat to human health, with consequences we’re only beginning to grasp.

THE UBIQUITY OF MICROPLASTICS

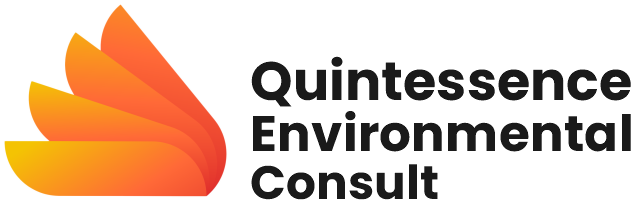

Microplastics originate from two main sources: primary and secondary. Primary microplastics are intentionally manufactured, such as microbeads in exfoliating scrubs or synthetic fibres from polyester clothing, which shed thousands of particles per laundry cycle. Secondary microplastics form when larger plastics, like bottles or packaging, fragment due to sunlight, ocean waves, or wind. (3) These particles persist for centuries, and their small size of 5mm allows them to infiltrate ecosystems effortlessly, entering the food chain through plankton, fish, and even crops irrigated with contaminated water. From Arctic ice cores to Himalayan snow, no environment remains untouched. (19)

HOW DO MICROPLASTICS ENTER THE HUMAN BODY?

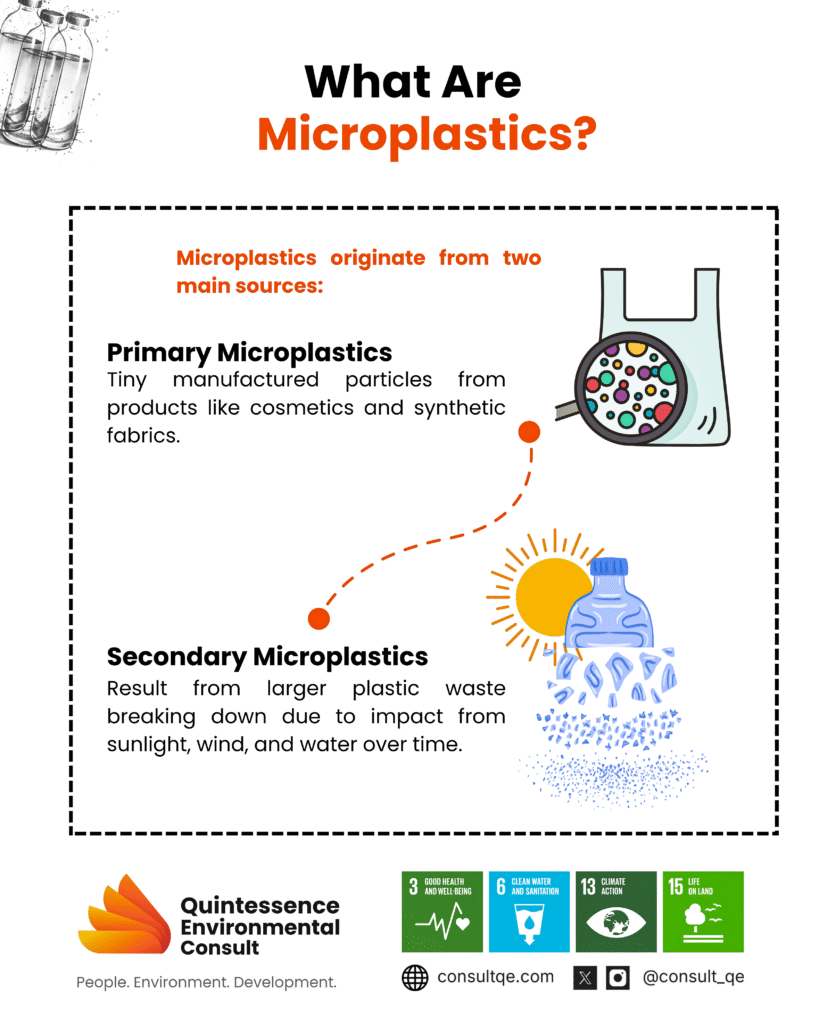

Microplastics can enter the human body through three primary pathways such as ingestion, inhalation, and dermal absorption.

- Ingestion: This is the most common route. Seafood, particularly shellfish and fish, often contains microplastics absorbed from polluted oceans. Bottled water, a staple for many, harbours up to 325 particles per litre (11) while table salt adds roughly 2,000 microplastic particles to our diets annually. (13)Even produce grown in contaminated soil introduces these particles into our bodies. Once ingested, microplastics travel through the digestive system, with studies detecting them in stool, liver, and colorectal tissues.

- Inhalation: Indoor air is polluted by synthetic textiles and household dust. Outside, tire wear, industrial emissions, and construction dust containing microplastics fill the atmosphere. A study in South Korea highlighted that Indoor air, polluted by synthetic textiles and household dust, contributes 1.5 times more microplastics than outdoor air. These particles lodge deep in lung tissue, triggering inflammation and oxidative stress, factors linked to respiratory diseases. (20)

- Dermal absorption: Although less understood, it is a growing concern. Microbeads in cosmetics penetrate hair follicles, while synthetic fabrics release fibres that cling to our skin. A 2025 pilot study at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) revealed that chewing gum releases up to 3,000 microplastic particles per piece into saliva, regardless of whether the gum base is synthetic or natural. Polyethylene was the most abundant polymer. (1) Chemicals like BPA and phthalates, which leach from plastics, can dissolve into sweat and seep into the bloodstream.

HEALTH IMPACTS OF MICROPLASTICS IN NIGERIA

Nigeria is a prime consumer of plastic, globally ranked as ninth (9th) for plastic pollution, with an estimated 2.5 million tons of plastic waste generated annually, having less than 12% recycled. Microplastics have been detected in various environmental matrices across Nigeria, including rivers, sediments, and consumables, raising concerns about potential health impacts. (16) While direct human health case studies specific to Nigeria are limited, several studies have highlighted the presence of microplastics in the environment and their potential risks:

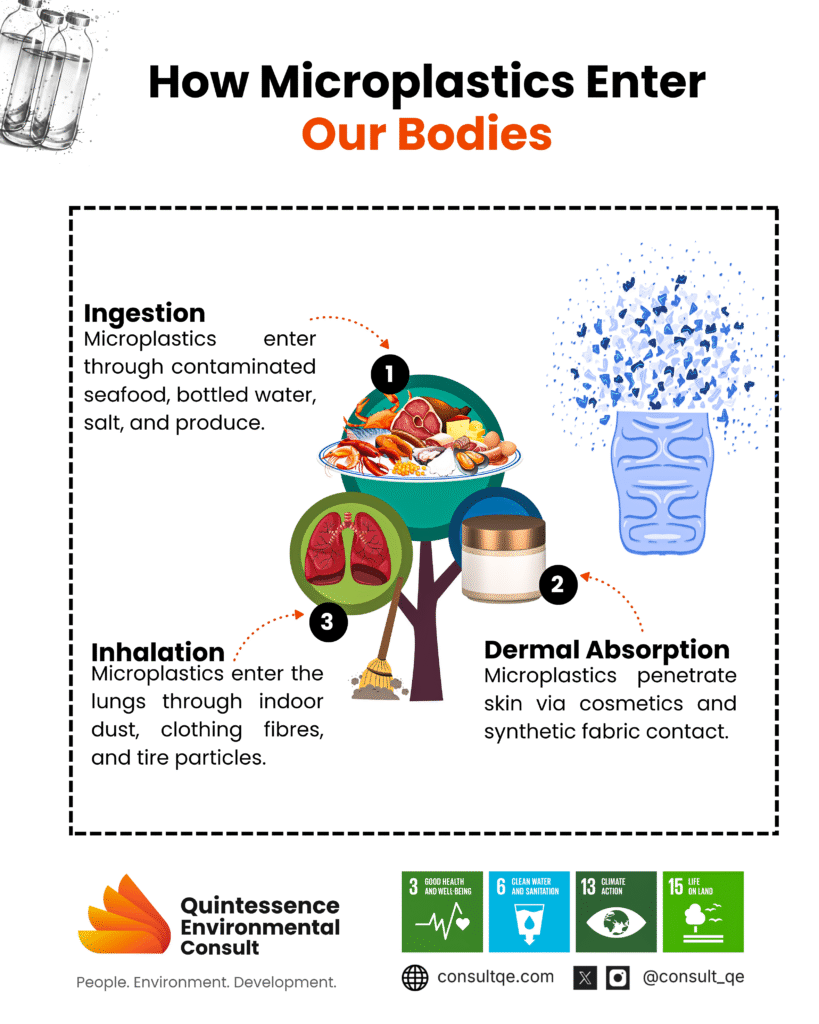

- Osun River Contamination: A 2024 study revealed that Nigeria’s Osun River contains the highest recorded levels of microplastics globally, with up to 22,079 particles per litre. This contamination poses significant health risks to communities relying on the river for drinking, bathing, and irrigation. (4)

- Borehole Water in Birnin Kebbi: Research in Birnin Kebbi detected microplastics in borehole water; the highest concentration was found in Tarasa, followed by Bayan Kara, Rafin Atiku, and GwadanGwaji. This indicates that even groundwater sources are not immune to plastic pollution, potentially affecting human health through daily water consumption. (23)

- Microplastics in Table Salt: A study analyzing commercial table salts in South-West Nigeria found microplastic contamination, suggesting that everyday food items can be a source of microplastic ingestion for consumers. Based on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommended daily salt intake of 5g, the study estimated that Nigerian adults could consume an average of 21.9 microplastic particles per year. (15)

- Fish from Kubanni Reservoir: Investigations into fish (Clarias gariepinus (Catfish) and Oreochromis niloticus (Nile Tilapia) from the Kubanni Reservoir in Zaria)uncovered microplastic particles within their systems, raising concerns about the transfer of microplastics to humans through the consumption of contaminated seafood. (12)

- Sediment Contamination in Rivers State: Studies in the brackish water estuaries of Rivers State identified microplastics in sediments, which can harbour heavy metals, potentially leading to compounded health risks for local populations through environmental exposure. (7)

Furthermore, emerging global research indicates that microplastics pose significant health risks by infiltrating various human organs. Studies have linked their presence in arterial plaques to a 4.5-fold increased risk of heart attacks and strokes, while elevated levels in brain tissues, particularly among dementia patients. (2)(10) Additionally, endocrine-disrupting chemicals like BPA and phthalates found in plastics are associated with hormonal imbalances, reduced fertility, and conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Microplastics have also been detected in the liver, potentially contributing to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and in the gut, where they may disrupt microbial balance and fuel inflammation linked to diabetes. (2) Microplastics can generate reactive oxygen species that damage DNA and proteins, pathways associated with cancer development. (6)

MITIGATION STRATEGIES

The key challenges of implementing the mitigation strategies for microplastics are major in low-income communities:

- Individual Action: Substitute plastic containers for glass or stainless steel, especially when microwaving. Use water filters certified to remove microplastics, choose natural fabrics like cotton over polyester, and reduce the consumption of processed foods. (8)

- Community and Industry Accountability: Install HEPA (high efficiency particulate air) air purifiers to trap airborne particles and attach microfiber filters to washing machines, preventing 80% of plastic fibres from entering waterways. (22) Participating in beach cleanups helps stop larger plastics from fragmenting into microplastics. Companies must phase out single-use plastics and toxic additives. Hospitals, for instance, can adopt reusable surgical tools to cut plastic waste. (14)

- Policy: The 2024 UN Plastic Treaty aims to reduce global plastic waste by 20% by 2030 through circular economy principles. (18) The Basel Convention regulates the transboundary movement of plastic waste, reducing microplastic leakage by improving waste management practices in developing nations. (3) The US Microbead-Free Waters Act (2015) prohibits microbeads in rinse-off cosmetics and personal care products. Nigeria’s National Policy on Plastic Waste Management (2021) aims to phase out single-use plastics (e.g., sachets, bottles) by 2025 and enforce an Extended Producer Responsibility Program (EPR) for plastic producers. (5) Bans on single-use plastics, like those in Lagos state-Nigeria, Canada and Malaysia, and stricter recycling standards are also critical steps. (9)

- Sustainable practices: Bioplastics made from algae or plant cellulose (Seaweed-Based Materials, Mushroom Packaging), Stainless Steel & Glass, Wood & Ceramics, offer eco-friendly alternatives. Advanced Filtration Systems in Wastewater treatment, to capture microfibers (e.g., Germany’s mandate for washing machine filters). (8) Public Awareness Campaigns Programs like the US EPA’s Safer Choice educate consumers on reducing plastic use. (21) Also, projects like The Ocean Cleanup’s River interceptors aim to capture plastic waste before it reaches the oceans, reducing marine microplastic sources by 70%. (17)

KEY CHALLENGES

The key challenges of implementing the mitigation strategies for microplastics are major in low-income communities:

- Resource Constraints: Developing countries may lack the financial and technical resources to implement and enforce sustainable alternatives, as they often come with higher initial costs. For instance, purchasing glass containers or certified water filters may not be financially feasible for all individuals. Research & development of biodegradable alternatives, advanced filtration systems such as HEPA, and adequate wastewater treatment systems require substantial investment, which may not be readily available, especially in developing countries.

- Awareness and Education: There is a general lack of awareness about the sources of microplastics, exposure and the benefits of sustainable alternatives. Hence, individuals and communities may not prioritize, engage and/or understand the importance of such changes, as plastic products are deeply integrated into their daily life, due to their convenience. Changing long-standing habits requires significant motivation and support.

- Market Acceptance/ Industry Resistance: New sustainable products may face challenges in gaining market acceptance due to higher costs and limited consumer awareness. Industries may resist changes due to concerns about increased operational costs and potential impacts on profitability. For example, transitioning to reusable surgical tools in hospitals involves significant investment and changes to established protocols.

- Global Coordination and Policy Enforcement: Microplastic pollution is a transboundary issue, necessitating coordinated international efforts. Ensuring compliance with policies and regulations requires robust monitoring and enforcement mechanisms, which may be lacking in some developing regions. Disparities in policy adoption and enforcement mechanisms across countries can undermine the global initiatives. Policies that impose restrictions on plastic use may face opposition from industries and political entities concerned about economic impacts.

RECOMMENDATION

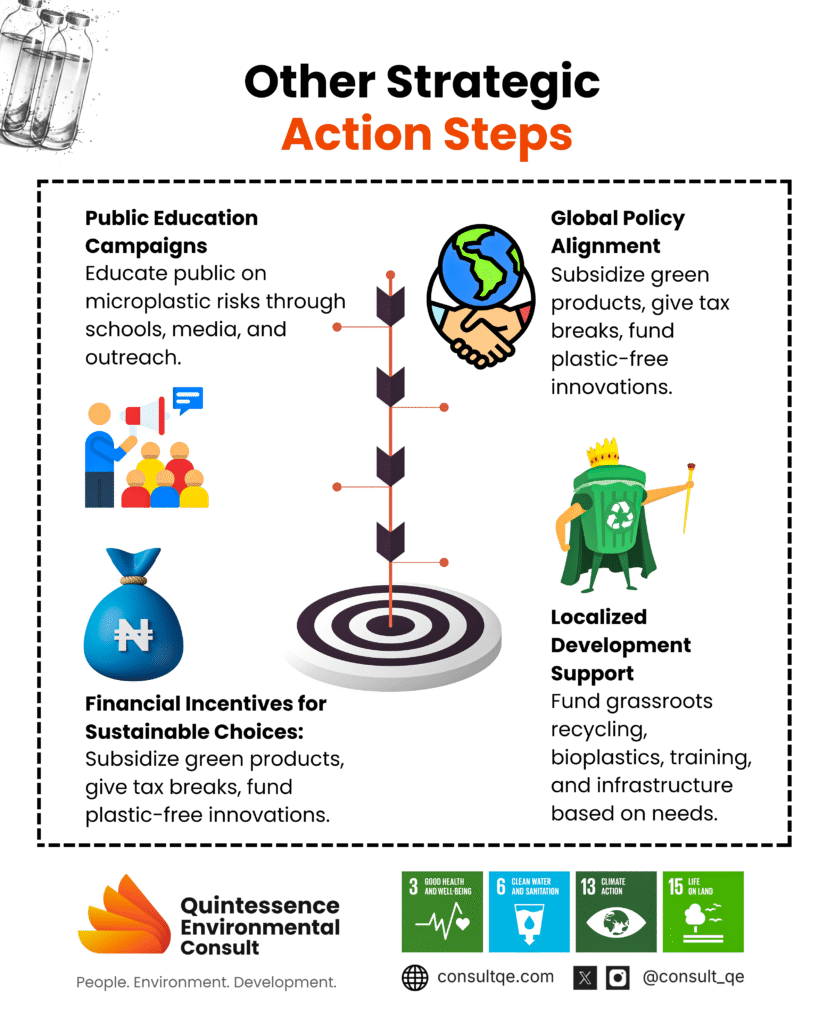

Mitigating microplastic pollution demands a multifaceted strategy encompassing individual actions, community involvement, industry accountability, policy enforcement, and sustainable practices. The key recommendations are as follows:

- Individuals’ contribution by adopting affordable, eco-friendly alternatives, such as reusable containers and certified water filters. Governments and organizations can support these efforts through subsidies and public education campaigns that raise awareness about the health risks associated with microplastics and promote behavioural changes, like choosing natural fabrics over synthetic ones and reducing processed food consumption.

- Community-led initiatives and workshops to further disseminate knowledge and practical strategies for minimizing plastic use.

- Community participation in local cleanup to prevent larger plastics from fragmenting into microplastics.

- Incentivizing or mandating industries to phase out single-use plastics and adopt sustainable alternatives.

- Strengthen the implementation of regulations like Nigeria’s National Policy on Plastic Waste Management, which aims to reduce plastic waste and promote recycling.

- Invest in research and infrastructure by allocating resources for studying microplastic impacts, supporting biodegradable alternatives, and developing sustainable waste management systems, infused with advanced filtration systems to capture microplastics before they enter natural water bodies.

- Conduct public campaigns to educate and raise awareness on the detrimental impacts of microplastics in the human body, and the effectiveness of adopting sustainable, eco-friendly alternatives.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the infiltration of microplastics into the human body presents a profound public health crisis with far-reaching implications. As evidence mounts on linking microplastic exposure to cardiovascular diseases, cognitive decline, hormonal disruption, organ damage, and even cancer, it becomes clear that urgent coordinated action is needed. The omnipresence of microplastics in our food, water, and the air we breathe, as well as the clothes we wear, demands that we rethink our reliance on plastic and its long-term impacts on human health.

Individuals must embrace behavioural shifts, industries should innovate eco-friendly alternatives, and policymakers must implement and enforce strong regulations to support the UN Plastic Treaty. With sustained commitment, global collaboration in supporting low-income communities, and investment in research and technologies, we can reduce microplastic pollution and safeguard both our environment and human well-being.

The time to act is now, before the invisible threat of microplastics becomes an irreversible legacy in our bodies and ecosystems.

REFERENCES

- American Chemical Society. (2025). Chewing gum can shed microplastics into saliva, pilot study finds. [online] Available at: https://www.acs.org/pressroom/presspacs

/2025/march/chewing-gum-can-shed-microplastics-into-saliva-pilot-study-finds.html - Barboza, L.G.A., et al. (2024). Detection of microplastics in human tissues and organs: A scoping review. Journal of Global Health, 14, 04036. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/

PMC11342020/ - Basel Convention. (2022). Plastic Waste Amendments: Overview and implications. [online] Available at: https://www.basel.int

- Environmental Analysis, Health and Toxicology. (2023). Abundance and shapes of microplastics in Nigeria’s Osun River. [online] Available at: https://eaht.org/m/journal/view.php?number=970

- Federal Ministry of Environment (2021). National Policy on Plastic Waste Management. [online] Available at: https://environment.gov.ng/plastic-waste-policy

- Food Packaging Forum. (2025). Two studies associate microplastic exposure with cancer. [online] Available at: https://foodpackagingforum.org/news/two-studies-associate-microplastic-exposure-with-cancer

- Isaac, I.U. (2025). Health risk assessment of heavy metals in microplastics in sediments: A case study of selected rivers, South-South, Nigeria. International Journal of Health and Pharmaceutical Research, 10(3),

pp.126–138. Available at: +Rivers%252C+South-South%252C+Nigeria”>https://www.

iiardjournals.org/abstract.php?id=59083&j=IJHPR&pn=Health+

Risk+Assessment+of+Heavy+Metals+in+

Microplastics+

in+

Sediments%2C+a+case+study+of+selected+

Rivers%2C+South-South%2C+Nigeria - Kumar, S., et al. (2025). Exploring sustainable strategies for mitigating microplastic pollution. Environmental Advances, 3, 100045. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/

article/pii/S2590182625000190 - Lagos State Government (2022). Ban on single-use plastics in Lagos: Implementation update. [online] Available at: https://lagosstate.gov.ng/single-use-plastics-ban

- Leslie, H.A., et al. (2024). Bioaccumulation of microplastics in decedent human brains. Nature Medicine, 30, pp. 456–463. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-024-03453-1

- Mason, S.A., Welch, V.G. and Neratko, J. (2018). Synthetic polymer contamination in bottled water. Frontiers in Chemistry, 6, p.407. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2018.00407.

- Onaji, M.O., Abolude, D.S., Abdullahi, S.A., Faria, L.D.B. & Chia, M.A. (2025). Analysis of microplastic contamination and associated human health risks in Clarias gariepinus and Oreochromis niloticus from Kubanni Reservoir, Zaria Nigeria. Environmental Pollution, 364(Pt 1), 125328. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2024.125328

- Papadopoulos, L. (2018) ‘You could be ingesting up to 2000 microplastics a year through salt’, Interesting Engineering, 18 October. Available at: https://interestingengineering.com/

science/you-could-be-ingesting-up-to-2000-microplastics-a-year-through-salt - Rahman, A., et al. (2024). Microplastics: The hidden danger. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 429, 128329. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/

science/article/pii/S0021755724001360 - Shokunbi, O.S., Jegede, D.O. & Shokunbi, O.S. (2023). A study of the microplastic contamination of commercial table salts: A case study in Nigeria. Environmental Health Engineering and Management, 10(2), pp.217–224. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/

publication/372053127_A_study_of_the_

contamination_of_

commercial_table_salts_A_case_study_

in_Nigeria - Sogbanmu, T.O. (2022). Plastic pollution in Nigeria is poorly studied, but enough is known to urge action. [online] The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/plastic-pollution-in-nigeria-is-poorly-studied-but-enough-is-known-to-urge-action-184591

- The Ocean Cleanup. (2025). Rivers. [online] Available at: https://theoceancleanup.com/rivers/

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2024). UN Plastic Treaty 2024: Draft agreement to end plastic pollution. [online] Available at: https://www.unep.org/plastictreaty

- World Economic Forum. (2025). How microplastics get into the food chain. [online] Available at: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/02/how-microplastics-get-into-the-food-chain/

- Wang, Y., et al. (2023). Health effects of microplastic exposures: Current issues and perspectives. Environmental Health Perspectives, 131(5), 056001. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/

PMC10151227/ - U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2025). Safer Choice. [online] Available at: https://www.epa.gov/saferchoice

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2025). What is a HEPA filter? [online] Available at: https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/what-hepa-filte

- Yahaya, T., Adewale, M.K., Ibrahim, A.B., Abdulkadir, B., Emmanuela, C.C. & Fari, A.Z. (2024). Abundance, characterization, and health risk evaluation of microplastics in borehole water in Birnin Kebbi, Nigeria. Environmental Analysis Health and Toxicology, 39, e2024017. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5620/eaht.2024017