KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Landfill mining transforms landfills from environmental liabilities into valuable resource hubs by excavating them to recover recyclable materials, such as plastics, metals, and glass.

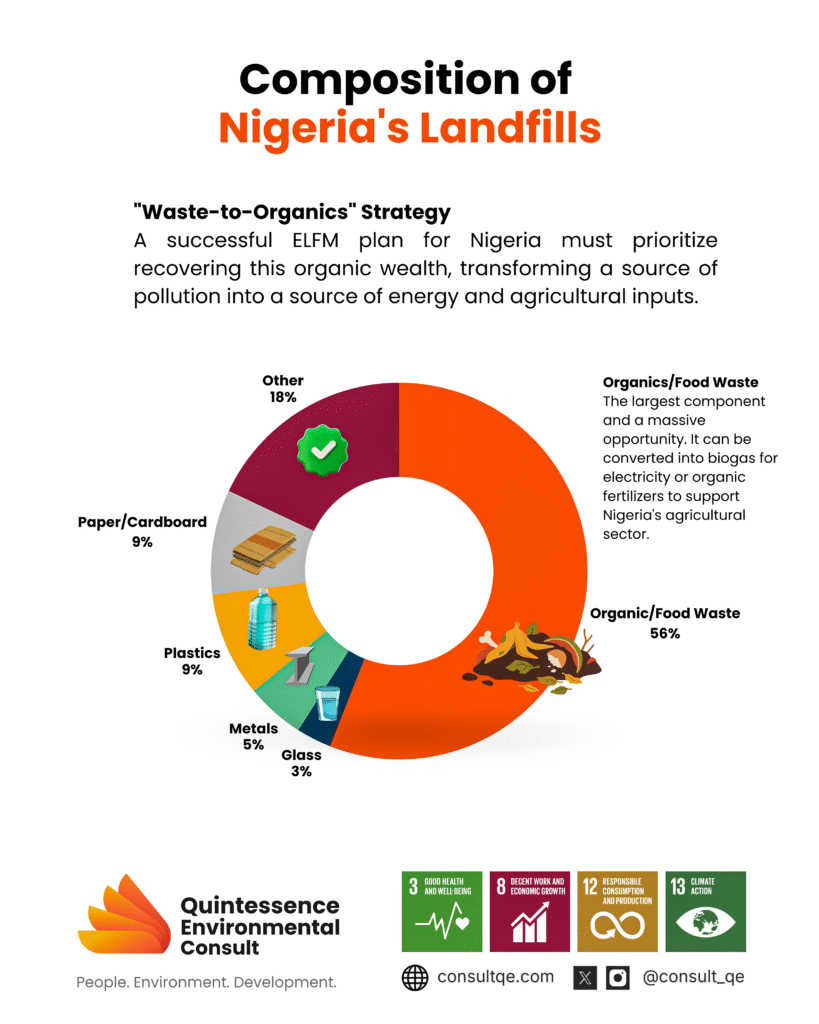

- Nigeria’s open dumpsites, which are common across the country, are particularly suited for mining because they are rich in organic matter (44-68%), which can be converted into energy and compost.

- Adopting this approach offers a dual benefit: it remediates environmental hazards by preventing the release of methane and toxic leachate, while also generating economic value through resource sales and land reclamation for urban development.

- The primary obstacles are weak government enforcement on waste management, the absence of policies that incentivize and promote recycling and resource recovery from waste, as well as high costs and technological complexities.

INTRODUCTION

For decades, landfills have been a quick, out-of-sight solution for our ever-growing piles of garbage. They’re often seen as the most economical way to deal with waste, but they come with significant environmental liabilities. Despite the global push for recycling, landfilling remains a dominant practice in many developing nations like Nigeria, leaving countless dumps full of accumulated waste, including valuable materials that are simply buried. Landfill mining is the process of excavating closed or active landfills to recover valuable resources, reclaim land, and mitigate environmental hazards. Unlike traditional waste management, which focuses on handling new waste, landfill mining goes back to the existing landfill to reclaim a treasure trove of recyclable and reusable resources such as metals, plastics, and glass. 5 This reduces the need for virgin materials and supports a circular economy.

AN ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL OPPORTUNITY

Landfill mining offers unique advantages over traditional waste management methods by providing both economic and environmental benefits. One of the most direct economic gains comes from resource and energy recovery. Landfill mining actively reclaims valuable resources like metals, plastics, and glass, which can be sold back into the market, reducing the need for virgin materials. 6 The combustible portion of the waste can also be used in waste-to-energy plants to generate electricity or heat, creating an additional revenue stream.

Beyond these immediate sales, the most substantial economic benefit often stems from land reclamation and remediation. By excavating the buried waste or open dumps, the land can be repurposed for more valuable uses, such as commercial or residential development. This not only creates new value but also helps municipalities avoid the substantial long-term costs of landfill closure, monitoring, and environmental cleanup. This process also significantly contributes to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. By removing the source of organic waste, landfill mining prevents the long-term production of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, making it a major win for the environment. 3 Lastly, creating new “air space” within existing landfills reduces the need for costly new landfill sites, generating future revenue from tipping fees and further bolstering the project’s economic viability.

THE CASE FOR LANDFILL MINING IN NIGERIA

The adoption of landfill mining, a practice explored in developed nations to reclaim land and reduce environmental liabilities, is uniquely suited to Nigeria’s specific waste management challenges. According to a December 2022 investigation by Punch Newspaper 9, only three Nigerian states have sanitary landfills, with the remaining 33 relying on open dumpsites. This widespread use of open dumping creates significant environmental and public health crises. The unsanitary conditions serve as fertile breeding grounds for disease vectors like rodents and mosquitoes, directly contributing to Nigeria’s status as the world’s most malaria-endemic country. 11. Additionally, the practice of open burning at these sites releases carcinogens into the air, fueling high rates of air pollution and obstructing traffic4.

Despite these issues, the composition of Nigeria’s waste presents a significant opportunity. The waste is notable for its high percentage of organic matter, which constitutes between 44% and 68.4% of the total volume². It also contains valuable recyclables like plastics, paper, metals, and glass. Given that this composition is based on open dumpsites, Nigeria has a unique opportunity to adapt landfill mining practices to excavate valuable resources from these sites. This approach will not only address decades of environmental contamination but also create thousands of green jobs, unlock significant economic value, and accelerate the nation’s transition to a resilient circular economy. Ultimately, adopting landfill mining can help Nigeria meet its net-zero commitments while reclaiming land for urban development.

BARRIERS TO ADOPTING LANDFILL MINING PRACTICES

The adoption of landfill mining in Nigeria’s open dumpsites faces significant barriers that go beyond the technical aspects of waste valorization.

- Financial and technological barriers: This presents a significant obstacle to the adoption of landfill mining in Nigeria. The process is highly capital-intensive, demanding a substantial upfront investment in specialized heavy machinery for excavating and sorting waste. This financial burden is particularly challenging for a country where waste management systems are often underfunded. Operationally, the technology required is complex. The heterogeneous and degraded nature of waste in Nigeria’s open dumps makes automated sorting difficult, often requiring extensive, and often dangerous, manual labor. The excavation itself poses serious health and safety risks, as it can release harmful dust, pathogens, and toxic heavy metals such as lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), and arsenic (As) into the environment, endangering both workers and nearby communities¹. Nigeria lacks the skilled personnel and technical capacity to manage these complex, high-risk operations safely. Finally, the financial viability of landfill mining is not guaranteed. While revenue can be generated from selling recovered materials and energy, the market for these secondary resources can be volatile, and the low quality of the recovered material may make processing it uneconomical, posing a major risk to a project’s profitability.6

- Policy and Regulatory Barriers: The weak government enforcement of waste management is a major hurdle. Current laws, such as the Federal Environmental Protection Agency (FEPA) Act and the National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) Act, 8 view open dumpsites solely as a problem to be contained in a landfill, not as a source of valuable resources. The absence of policies that incentivize and promote recycling and resource recovery from waste also makes it nearly impossible for landfill mining practices to get the necessary permits, secure land rights, or attract the investment needed to get started.

- Social and Cultural Barriers: This primarily stems from public perception and the role of the informal waste sector. There is a low level of public awareness regarding the long-term benefits of proper waste management and landfill mining. This lack of understanding can lead to community resistance, as residents are often concerned about the immediate environmental and health impacts of excavating old dumpsites, such as dust, odors, and potential exposure to contaminants. Compounding this issue is the widespread presence of informal waste pickers who rely on dumpsites for their livelihood. A formal landfill mining operation on the open dumpsites, while beneficial for the country, could displace these workers, creating significant social and economic disruption that requires a carefully designed and justly implemented transition plan. 10

RECOMMENDATION

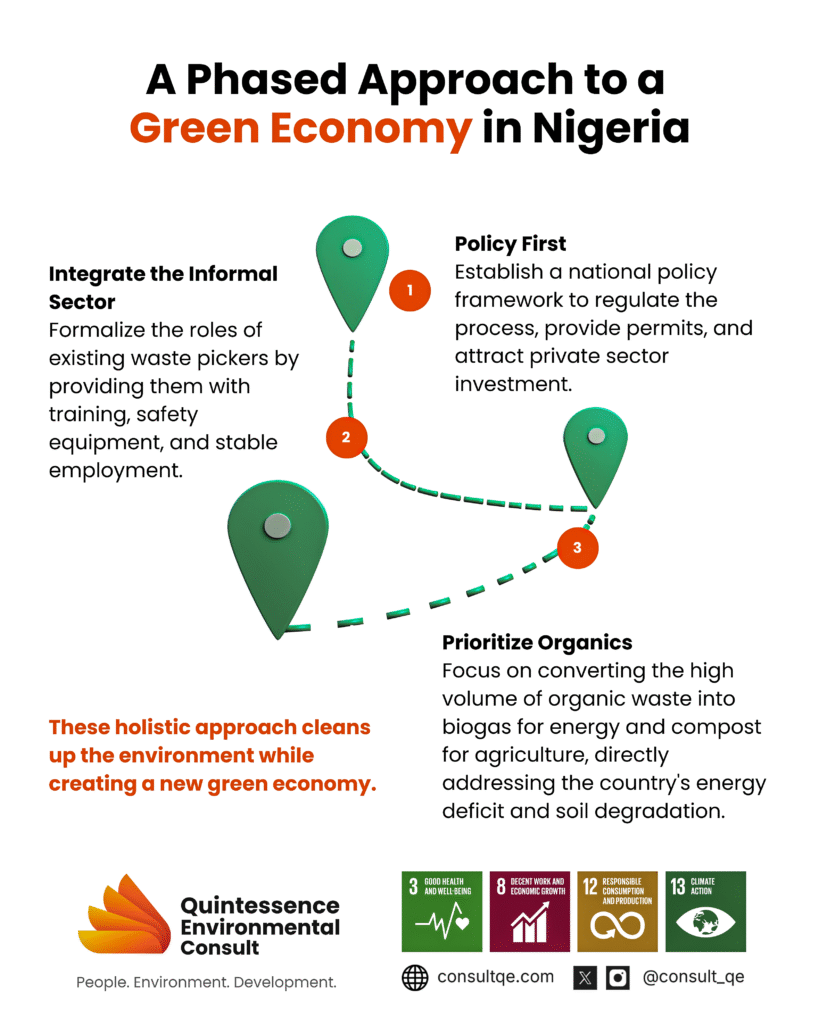

Nigeria can adopt landfill mining by strategically transforming its numerous open dumpsites into resource hubs. Given that these sites are rich in valuable organic waste and recyclables, the country can implement a “waste-to-value” strategy. This would involve a phased approach that combines remediation with resource recovery. First, a national policy framework must be established to regulate the process and attract private sector investment. Second, the informal waste-picking sector, which already operates at these sites, should be integrated into the formal system, providing them with training, safety equipment, and stable employment. Finally, the focus of the mining operation should be on excavating and sorting waste using low-cost, context-specific technologies to recover recyclables. The most significant opportunity lies in converting the high volume of organic waste into biogas for energy and compost for agriculture, directly addressing the country’s energy deficit and soil degradation. 7 This holistic approach not only cleans up decades of environmental contamination but also creates a new green economy.

CONCLUSION

The transformative potential of promoting and adopting landfill mining practices for Nigeria’s open dumpsites is immense. It offers a clear and actionable strategy to help curb the crises of environmental pollution. This adoption will transform its old dumpsites into a powerful engine for sustainable development. This approach will not only clean up the environment but also help power the economy, create thousands of jobs, and build a stronger, more stable future that advances toward a circular economy where waste becomes wealth. The choice is not whether to act, but how to begin.

- Agyei, O. (2017). “Assessment of Heavy Metal Pollution from Dumpsites and Its Health Implications.” Journal of Environmental Protection, 8(1), 1-10.

- Agam, J. N., & Ogbodo, B. A. (2018). “Physical and chemical characterization of municipal solid waste in Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria.” Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 11(2), 1-8.

- D.J. van der Zee, M.C. Achterkamp, B.J. de Visser, Assessing the market opportunities of landfill mining, Waste Management, Volume 24, Issue 8, 2004, Pages 795-804, ISSN 0956-053X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2004.05.004.

- Eze, E. S., & Nwabunike, N. C. (2019). “Impact of open burning of solid waste on air quality and public health in Enugu, Nigeria.” Nigerian Journal of Technology, 38(3), 674-681.

- Jan, N., et al. (2023). “Sustainable Solid Waste Management through Landfill Mining.” Journal of Environmental Engineering, 149(3), 04022132.

- L. Canopoli, B. Fidalgo, F. Coulon, S.T. Wagland, Physico-chemical properties of excavated plastic from landfill mining and current recycling routes, Waste Management, Volume 76,2018, Pages 55-67, ISSN 0956-053X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.03.043.

- Olusunmade, O., Yusuf, T., & Ogunnigbo, C. (2019). Potential for energy recovery from municipal plastic wastes generated in Nigeria. International Journal of Human Capital in Urban Management, 4(4), 295–302. https://doi.org/10.22034/IJHCUM.2019.04.05

- Omole, D. O., & Alakinde, O. S. (2023). Health and environmental implications of the landfill in Igando, Lagos State, Nigeria. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/389575033_HEALTH_AND_ENVIRONMENTAL_IMPLICATIONS_

OF_THE_LANDFILL_IN_IGANDO_LAGOS_STATE_NIGERIA - Punch Newspaper, “Only 3 states have sanitary landfills in Nigeria, 33 operate open dumping system,” December 12, 2022. https://punchng.com/33-states-lack-landfills-dispose-waste-openly-report

- Sani, B. I., & Aliyu, M. S. (2020). “Socio-economic analysis of informal waste pickers in Kaduna Metropolis, Nigeria.” International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 17(1), 321-330.

- World Health Organization. (2022). World Malaria Report 2022. WHO Press.