KEY TAKEAWAYS

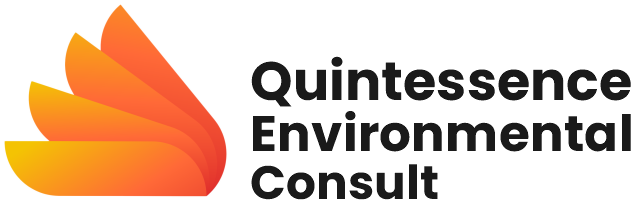

- Nigeria’s construction sector contributes approximately 23% of national CO2 emissions (largely from cement production) and faces escalating costs and economic risks due to reliance on imported materials.

- Compressed Stabilized Earth Blocks (CSEBs) offer a scalable alternative, emitting 40-50% less CO2 than concrete blocks while providing structural integrity for up to four-story load-bearing structures.

- Indigenous earth-based materials offer high thermal mass, potentially reducing cooling energy demand. Engineered Bamboo provides a rapidly renewable structural material with high strength.

- Mainstreaming is hindered by the “Perception Barrier” (associating earth with poverty) and a critical lack of national standards and building codes for materials like CSEBs and engineered bamboo.

- Essential steps include government-mandated National Standards and financial incentives, coupled with academic integration of vernacular principles and region-specific research into construction curricula.

INTRODUCTION

The necessity for a shift in the Nigerian construction industry is driven by dual and intersecting crises: the enormous national housing deficit and the growing environmental urgency for sustainability. Rapid urbanization has pushed formal housing costs to extremes, effectively pricing millions of citizens out of the market (11). This crisis is exacerbated by the sector’s persistent reliance on imported, carbon-driven models such as steel & cement production, which are detrimental to low-cost housing goals and increase the nation’s carbon footprint (27). Integrating low-carbon, culturally resonant materials is therefore vital for achieving economic stability, social inclusion, and ecological sustainability (17). Nigeria needs to build at least 550,000 new homes each year, requiring about ₦5.5 trillion annually for the next decade to close the national housing deficit- Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (28).

THE IMPERATIVE FOR CHANGE

Nigeria’s reliance on conventional building materials has created unsustainable burdens. The sector’s dependency on imported steel and cement results in rapidly rising construction costs and exposes regional economies to foreign exchange risks that make formal housing prohibitively expensive (22).

The construction sector contributes approximately 23% of Nigeria’s total CO2 emissions. This high figure is directly linked to the manufacturing of high-carbon materials like cement, which emits about 0.9kg of CO2 of or every kilogram produced. Manufacturing cement requires burning fossil fuels at extremely high temperatures in kilns, which also releases harmful air pollutants like nitrogen and sulfur oxides. This pollution severely deteriorates air quality, particularly near industrial sites, and poses serious health risks. Studies in Nigeria have confirmed heavy metal contamination (e.g., lead and zinc) in soils near cement factories, posing a direct threat to public health (19, 25). Furthermore, establishing and operating these facilities often results in the irreversible loss of valuable farmland and natural vegetation (20).

Sustainable Enhanced Indigenous Materials

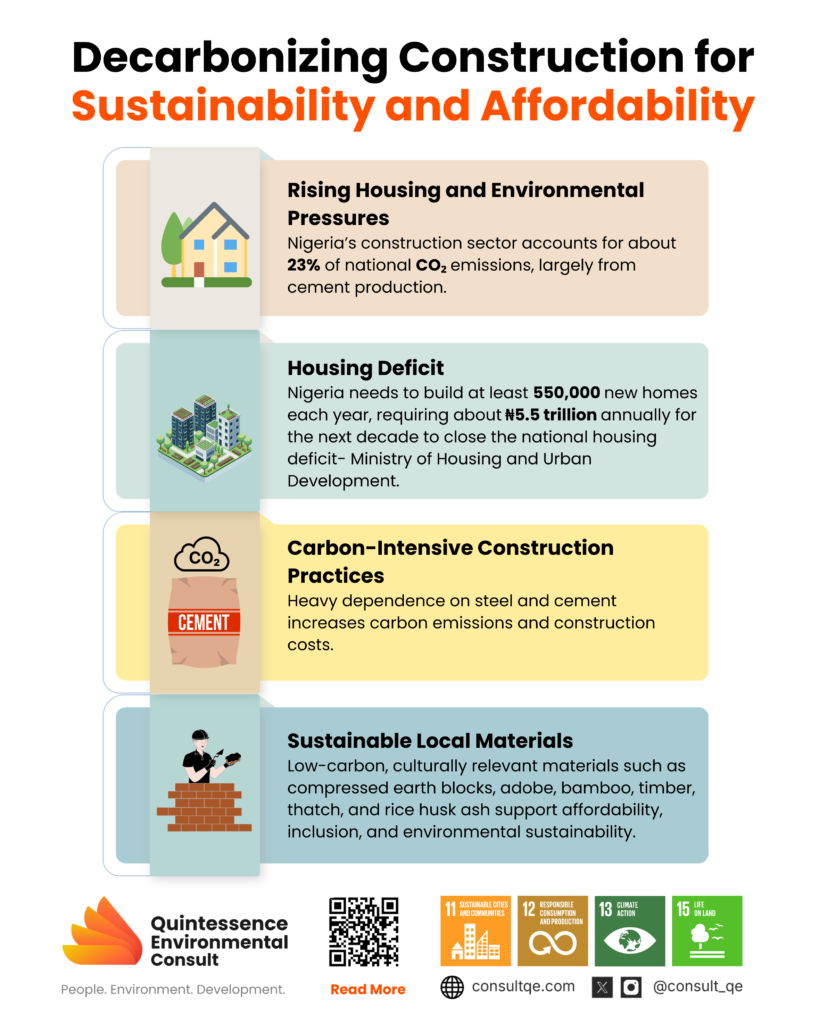

The most viable pathway for modern, high-density, and climate-resilient development involves upgrading and engineering traditional local materials.

A. Compressed Stabilized Earth Blocks (CSEBs)

Laterite, a local soil rich in iron, is widely available across central and southern Nigeria (12). To turn this soil into a modern building material, we use stabilization and compression. Stabilization involves mixing the laterite with small amounts of additives typically 5-10% cement, lime, or ash. This process significantly hardens the soil, making the blocks far more durable and resistant to water damage than traditional mud (10, 15). Research proves that adding minimal stabilizers greatly enhances the blocks’ strength. When properly engineered with reinforcing ring beams and foundation plinths, they are structurally suitable for three-to four-story load-bearing structures (10).

For example, compressed blocks stabilized with just 2% cement and 8% Guinea Grass Ash (GA) showed a 27.81% increase in compressive strength (3). Similarly, cow bone ash powder is a potent stabilizer that maintains high strength while allowing developers to use less expensive cement (4). Because CSEBs are made locally, they drastically reduce the energy and carbon emissions (emit 40-50% less CO2 than concrete blocks) associated with manufacturing and transport (17). Furthermore, their high thermal mass allows them to naturally regulate indoor temperatures, boosting energy efficiency and reducing the need for expensive air conditioning (16).

B. Engineered Bamboo

Bamboo is a rapidly renewable resource, particularly abundant in Southern Nigeria’s rainforest regions. Often called ‘green steel,’ bamboo is a naturally growing grass that matures in just three to five years, making it highly sustainable compared to hardwoods that take decades (11). Raw bamboo is vulnerable to pests and moisture. Modern engineering addresses this through chemical treatment, curing, and lamination to create durable, high-strength engineered products (e.g., scrimber); a composite material that is strong, beautiful, and meets high architectural standards (6, 21). When properly engineered, bamboo has a tensile strength comparable to steel. The government recognizes engineered bamboo’s potential to quickly expand access to low- and middle-income housing and reduce the national carbon footprint (11, 21).

CURRENT PRACTICES IN NIGERIA

Successful projects around the world and in Nigeria validate the potential of indigenous materials for high-quality, modern construction. The Nigerian Building and Road Research Institute (NBRRI) actively promotes the use of laterite and clay (CSEB) for mass housing (14). The viability of enhanced materials has been proven even in challenging environments. In Borno State, for instance, a project supported by humanitarian agencies successfully used minimal cement combined with local materials like Gamba grass and Chaqqa straws to create durable Stabilized Compressed Earth Bricks (SCEBs) (18). This success demonstrates the material’s resilience and affordability for formal housing programs.

A notable aesthetic example is the G.A.S. Farm House in Ikise, Nigeria, designed by MOE+ Art Architecture. This high-profile residency utilized an estimated 40,000 earth bricks created from soil dug up during the foundation process, and repurposed bamboo scaffolding for exterior screens, showcasing modern aesthetic quality and passive cooling designs (24).

LIMITATIONS AND CHALLENGES TO ADOPTION IN NIGERIA

Despite the strong evidence supporting local, sustainable materials, widespread adoption in Nigeria faces several deep systemic barriers.

A. Regulatory and Standardization Deficits

The primary roadblock is the government’s failure to formally recognize and integrate alternative materials. Key materials like engineered bamboo and stabilized earth blocks lack specific, integrated standards in the Nigerian National Building Code (NBC) (6, 9). While the NBC mentions sun-dried soil bricks (1), it does not cover modern stabilization techniques.

Because these materials are not regulated, they exist outside the formal system. For example, over 81% of bamboo used by contractors is informal and often untreated, failing to meet basic safety standards. Without clear NBC standards, securing structural approval or insurance for green projects remains difficult, trapping viable solutions in the informal market (5, 7, 9).

B. The Perception Barrier

The historical association of earth-based materials with poverty or “rural backwardness” remains the biggest non-technical hurdle. These materials are widely associated with low-income, rural, or temporary housing, leading to significant public scepticism (6, 11). This negative perception discourages potential homeowners and formal sector developers.

C. Technical Capacity and Knowledge Gaps

The ability to scale up indigenous materials is limited by critical knowledge deficits within the construction workforce. There is insufficient expertise and training in specialized techniques for quality CSEB production, proper treatment, and structural installation of engineered bamboo (13, 26). Furthermore, while the long-term cost of indigenous materials is lower, the initial high upfront cost of sophisticated compression and stabilization equipment required for mass production of quality CSEBs discourages small-scale manufacturers and limits market entry.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Achieving scalable sustainability requires the integration of research, policy, and design practice:

- Policy as a Driver: The government should introduce National Standards for CSEBs and engineered bamboo. The Nigerian Building and Road Research Institute (NBRRI) should be immediately funded and tasked with finalizing and integrating clear, mandatory technical standards for these materials into the National Building Code (NBC) (11, 14). This is necessary to build trust and allow major formal investment. Financial incentives, such as tax reductions, subsidies, or green certification systems (similar to LEED/EDGE models), should be implemented to make low-carbon indigenous materials financially logical for developers (14, 22).

- Research and Education: The Nigerian Building and Road Research Institute (NBRRI) requires adequate funding to aggressively pursue Research & Development. Priority areas include refining laterite stabilization formulas using local waste streams (e.g., cow bone ash, Guinea Grass Ash) and developing commercial prototypes for engineered bamboo (3, 4 ,11, 14). To close the skills gap, educational institutions should formalize curricula and vocational training in specialized earth and bamboo construction techniques. The engineering of local materials should also be integrated into the core architecture and engineering curricula.

- Public Awareness: To break the negative association of earth and bamboo with poverty, the government should invest in highly visible, aesthetically superior public buildings and institutions in major cities. These showcase projects should demonstrate the modern elegance, structural integrity, and superior thermal comfort of engineered indigenous materials, directly challenging public skepticism (2).

CONCLUSION

The modernization of Nigerian architecture using enhanced indigenous materials is essential for economic stability and climate resilience. Stabilized earth and bamboo are not only cost-effective, offering significant housing cost reductions, but are also vital tools for national decarbonization due to their drastically lower embodied energy and carbon footprints. Overcoming the barriers, primarily regulatory inaction and institutional resistance, requires the government to implement a focused framework: codifying standards, providing robust fiscal incentives, building capacity, and deploying high-visibility urban projects to change public perception.

REFERENCES

- Abdulkarim, B. A. (2005). Prospects for Earth Building. Kaduna, Nigeria: National Housing Policy.

- Abubakar, M. (2020). ‘Nigeria still faces major issues concerned with perceptions and attitudes towards earth building’. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Applied Science, 5(2), pp. 121–126.

- Adesina, M. J. (2021). ‘Improvement in properties of compressed laterite blocks stabilised with cement and guinea grass ash’. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning, 14(3), pp. 27–35.

- Adesina, M. J. (2023). ‘Stabilization potency of ordinary portland cement and cow bone ash powder on laterite for sustainable housing delivery in Nigeria’. Journal of Materials Science Research and Reviews, 7(2), pp. 110-121.

- Adibe, F. (2023). ‘Nigeria’s bamboo housing plan: opportunities, risks, and the standards needed for mass adoption’. Nigeria Housing Market. Available at: https://www.nigeriahousingmarket.com/real-estate-news-nigeria/nigerias-bamboo-housing-plan-opportunities-risks-and-the-standards-needed-for-mass-adoption

- Adibe, F. (2024). ‘Public Perception Remains a Critical Barrier’. Nigeria Housing Market. Available at: https://www.nigeriahousingmarket.com/real-estate-news-nigeria/nigerias-bamboo-housing-plan-opportunities-risks-and-the-standards-needed-for-mass-adoption

- Adewole, A. (2024). ‘Barriers and drivers to implementation of green building in Nigeria’. Onyia Construction. Available at: https://onyiaconstruction.com/2024/02/19/barriers-and-drivers-to-implementation-of-green-building-in-nigeria/

- Akintola, O. (2023). ‘The potential advantages that come with incorporating these local materials into the resort’s design’. Harvard International Journal of Education, Development and Construction Management, 5(3), pp. 120-135.

- Akintola, O. (2023). ‘Utilization of sustainable building rating tools among building professionals in Nigeria’. MDPI Journal of Sustainable Construction, 5(2), pp. 156-170.

- Alagbe, O. (2010). ‘A Review of Compressed Stabilized Earth Brick as a Sustainable Building Material in Nigeria’. Journal of Construction Project Management and Innovation, 1(1), pp. 46–62.

- Asanye, E. (2024). ‘Nigeria’s bamboo housing plan: opportunities, risks, and the standards needed for mass adoption’. Nigeria Housing Market. Available at: https://www.nigeriahousingmarket.com/real-estate-news-nigeria/nigerias-bamboo-housing-plan-opportunities-risks-and-the-standards-needed-for-mass-adoption

- Bello, A., Ige, J., & Ayodele, H. (2015). ‘Stabilization of Lateritic Soil with Cassava Peels Ash’. British Journal of Applied Science & Technology, 7(6), pp. 642–650.

- Daniel, O., Kayanula, M. & Quartey, P. (2018). ‘Lack of expertise, limited training, and overreliance on established construction methods’. Journal of Management and Sustainable Development, 8(2), pp. 110-125.

- Duna, S. (2021). ‘Mass Housing Through the Use of NBRRI Stabilized Earth Blocks’. Nigerian Building and Road Research Institute (NBRRI). Available at: https://nbrri.gov.ng/new/mass-housing-through-the-use-of-nbrri-stabilized-earth-blocks/

- Eze, J. (2020). ‘Impact of Traditional Building Techniques on Modern Construction in Southeastern Nigeria’. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Applied Science, 5(2), pp. 121–126.

- Habu, I. (2025). ‘Assessment of Skilled Workers Shortages in the Construction Industry in Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Abuja’. Engineering Research journal, 5(1), pp. 25-39.

- Ishaku, H. (2025). ‘Compressed stabilized earth blocks (CSEBs) are garnering increased attention because of their ability to lower environmental impact’. MDPI Journal of Materials and Construction, 5(2), pp. 88-102.

- Mercy Corps Nigeria (2022). ‘Improving the Quality of Mud Bricks Using Low-Cost Stabilization and Compression Techniques in Northeast Nigeria’. Mercy Corps Nigeria Research Report.

- Nwachukwu, I. (2021). ‘Heavy metal contamination in soils near cement plants in Nigeria’. Atmosphere, 12(9), 1111.

- Obajana Cement Plc (2021). ‘Environmental Impacts Assessment’. European Investment Bank. Available at: https://www.eib.org/files/pipeline/1191_summary_ocp_cpp_eia_en.pdf

- Odii, J. (2023). ‘Bamboo’s tensile strength, which rivals that of steel, make it a promising material for lightweight construction’. Nigeria Housing Market. Available at: https://www.nigeriahousingmarket.com/real-estate-news-nigeria/nigerias-bamboo-housing-plan-opportunities-risks-and-the-standards-needed-for-mass-adoption

- Okoroh, J. (2024). ‘Tackling fraudulent developers requires multi-faceted approach’. The Guardian (Nigeria). Available at: https://guardian.ng/property/tackling-fraudulent-developers-requires-multi-faceted-approach-2/

- Okoroh, J. & Chinwe, O. (2020). ‘The arrangement of windows in a building increased in number and size due to modernisation’. Scientific Research Publishing, 11(2), pp. 150-165.

- Omotayo, P. (2022). ‘The G.A.S. Farm House was designed by Papa Omotayo of MOE+’. World Architects. Available at: https://www.world-architects.com/es/projects/view/gas-foundation-farm-house

- Peralta, J. (2024). ‘Atmospheric Pollution and the Environmental and Health Impacts of Cement Manufacturing’. MDPI Journal of Environmental Health, 12(4), pp. 450-465.

- Udo, N. & Udo, I. (2020). ‘Technical and knowledge-related barriers hinder technology uptake’. International Journal of Education and Development, 14(3), pp. 221-235.

- Ugochukwu, M. & Chioma, O. (2015). ‘Traditional African architecture made certain that its use of the resources neither diminished their availability’. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 3(1), pp. 20–35.

- Dangiwa, A. M. (2024). Nigeria needs 550,000 housing units annually at ₦5.5 trillion to close housing deficit. Statement by the Minister of Housing & Urban Development. Federal Ministry of Housing & Urban Development, Abuja, Nigeria. https://fmhud.gov.ng/index.php/read/3290.