Why The Global Plastics Treaty Failed and What it Means for Nigeria

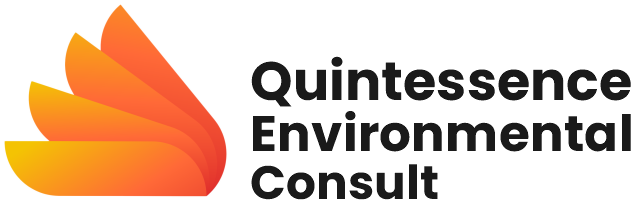

Each year, the world produces over 400 million tonnes of new plastic. In the absence of significant policy reforms, this figure is projected to increase by nearly 70% by 2040, according to a 2024 OECD policy scenario report8. The proposed Global Plastic Treaty aims to address plastic pollution across its entire lifecycle, covering production, consumption, waste management, and disposal. In addition, the treaty is expected to provide funding and technology transfer to support plastic waste management.

Formal negotiations on the treaty were led by the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC), which commenced in December 2022, with representatives from 175 countries participating. In addition, major financial institutions were expected to play a key role in promoting the development and implementation of the treaty within the global financial sector5. However, following the final round of talks (INC-5.2)7, held in August 2025 in Geneva, Switzerland, the Committee failed to reach a unified position. The breakdown of these negotiations has left the international community without a comprehensive, legally binding framework to effectively tackle the escalating plastic pollution crisis. A major impediment to progress was the INC’s reliance on consensus-based decision-making—a diplomatic mechanism that enables individual delegations to delay or obstruct collective outcomes. Attempts to reform this approach, including proposals for qualified majority voting in specific contexts, proved politically contentious and ultimately unsuccessful. Consequently, a small number of dissenting states were able to stall the entire negotiation process. This paper explores the main factors contributing to the negotiation deadlock and assesses the broader implications for Nigeria, one of Africa’s largest producers of plastic waste.

Building Smarter, Wasting Less: The Future of Sustainable Construction in Nigeria

INTRODUCTION

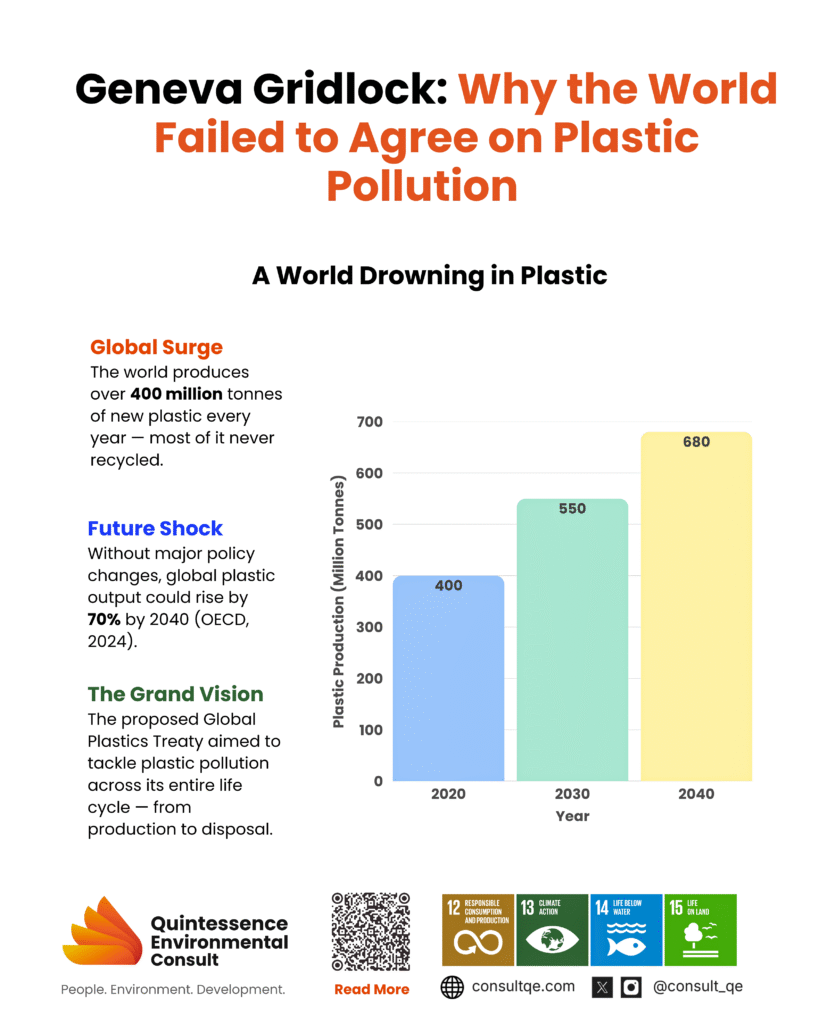

Imagine a building site where piles of cement bags, broken blocks, and timber cuttings grow higher than the house being built. This is the reality of many construction sites in Nigeria today. The waste generated not only drives up project costs but also pollutes the environment, worsening the housing crisis and undermining sustainable development. Nigeria is one of the fastest-urbanizing countries in Africa. According to the United Nations, more than half of Nigerians now live in cities, and by 2050, the urban population is expected to double (United Nations, 2019). This urban expansion has fueled a construction boom, with roads, housing estates, and commercial buildings springing up in almost every state. While this growth supports economic development, it has created a hidden challenge: the massive generation of construction waste.

Cement is Nigeria’s most commonly used building material, with annual consumption exceeding 20 million metric tons (Nigerian Bureau of Statistics, 2020). Yet at construction sites, it is common to see cement wasted during mixing, hardened leftovers dumped after setting, and bags spoiled by moisture before use. Timber, another widely used material, is often cut to sizes that leave large offcuts, while broken blocks and bent reinforcement rods are discarded without reuse.

This careless material culture contributes to high construction costs and environmental degradation.

Globally, the construction industry accounts for about 40% of solid waste generation (United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP], 2021). Though Nigeria lacks comprehensive national data, anecdotal evidence suggests construction waste is one of the largest contributors to solid waste in cities like Lagos and Abuja. Unless addressed, this problem will worsen as demand for housing and infrastructure grows.

Tyre Upcycling: Turning Waste into Circular Value

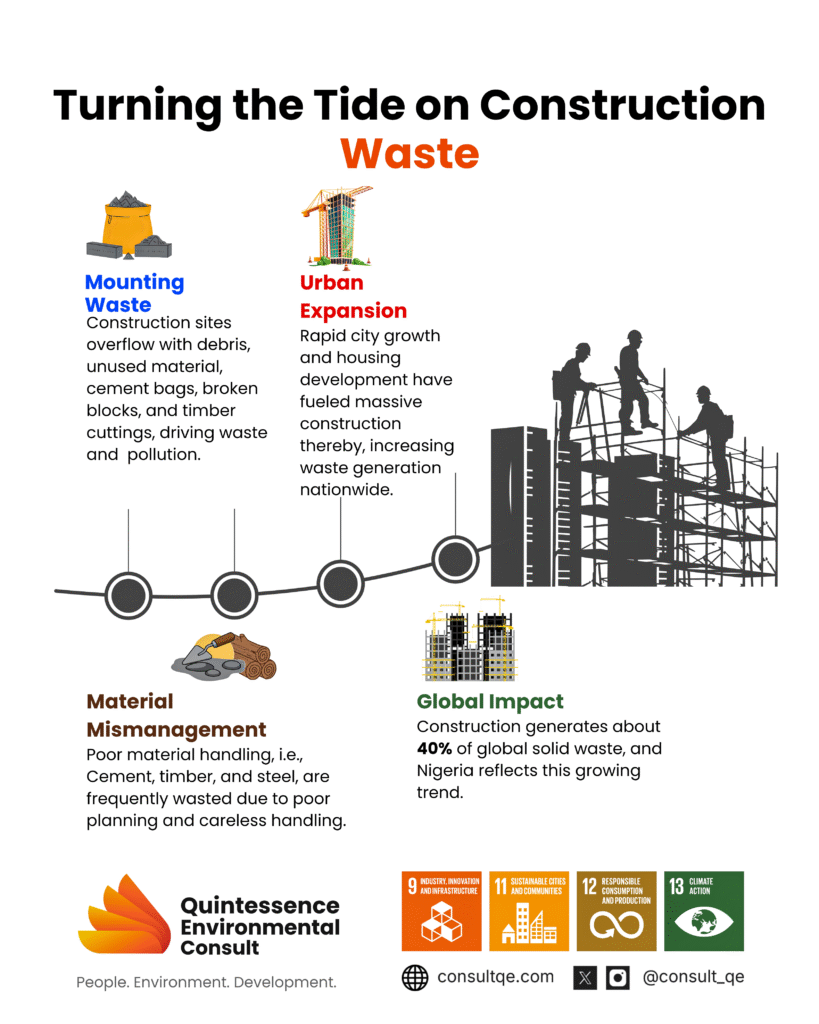

Every year, billions of tyres are manufactured, serving a vital role in transportation across the globe. However, once these tyres reach the end of their life, they pose a significant environmental challenge. Their durability and non-biodegradable nature cause them to accumulate in landfills or scrapyards, contributing to pollution through leaching of harmful chemicals, fire hazards, and the creation of breeding grounds for disease-carrying pests.

Tyres are highly engineered composites made from a blend of materials designed to ensure strength, flexibility, and durability. On average, they consist of 10–40% natural rubber for elasticity, 20–60% synthetic rubber (such as styrene-butadiene and butadiene rubber) for abrasion resistance, 15–30% carbon black or silica as reinforcing fillers, 10–15% steel for structural support in belts and beads, and 3–8% textile fibres such as nylon, polyester, or rayon for stability.

In addition, 5–10% chemical additives (including sulphur for vulcanization, oils, antioxidants, and resins) are incorporated to enhance resistance to heat, oxidation, and UV degradation. These components work together to create tyres that can withstand heavy loads, high temperatures, and constant friction, making them critical to modern transport systems.

Environmental Impact Of Plastic Additives In Nigeria: An Emerging And Overlooked Contaminant Of Concern

Plastic products often contain additives such as plasticizers, stabilizers, flame retardants, pigments, PFAS-based coatings, and biocides, which are incorporated into polymer matrices to enhance their performance. Since most of these additives are not chemically bonded to the polymers, they can leach out, evaporate, or be released along with micro- and nanoplastics into the environment.

While global concern about this chemical aspect of plastic pollution is increasing, in Nigeria—where plastic waste management faces challenges like high waste production, limited formal recycling, open dumping, and frequent flooding—these additives remain a largely overlooked but potentially significant source of environmental contamination (Ebere et al., 2019; Faleti, 2022).

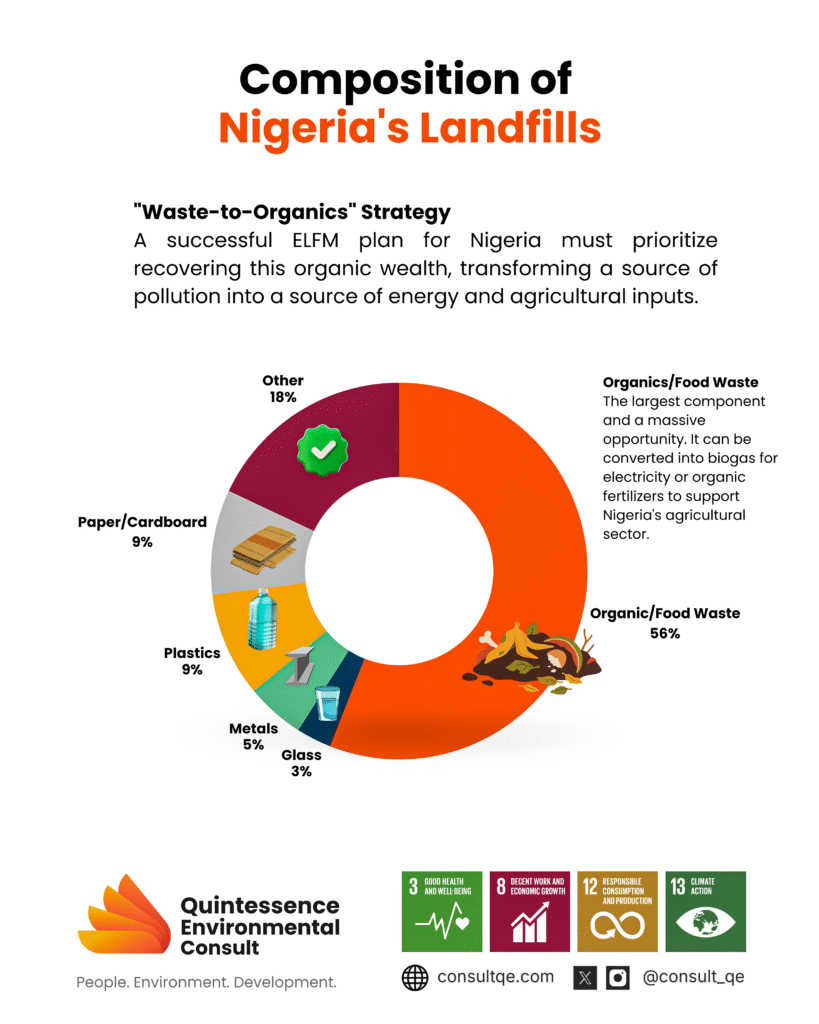

Landfill Mining in Nigeria: From Dumpsites to Green Economy

For decades, landfills have been a quick, out-of-sight solution for our ever-growing piles of garbage. They’re often seen as the most economical way to deal with waste, but they come with significant environmental liabilities. Despite the global push for recycling, landfilling remains a dominant practice in many developing nations like Nigeria, leaving countless dumps full of accumulated waste, including valuable materials that are simply buried.

Landfill mining is the process of excavating closed or active landfills to recover valuable resources, reclaim land, and mitigate environmental hazards. Unlike traditional waste management, which focuses on handling new waste, landfill mining goes back to the existing landfill to reclaim a treasure trove of recyclable and reusable resources such as metals, plastics, and glass. 5

This reduces the need for virgin materials and supports a circular economy.