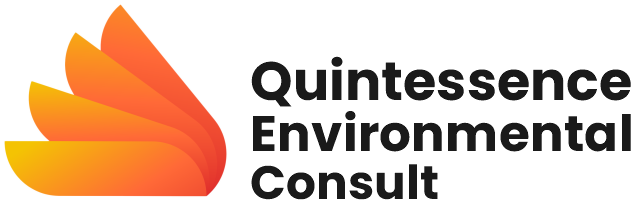

Reimagining Katsina: A Green Growth Vision for All

In an era defined by the need for sustainable development, Katsina State has taken a bold and strategic step forward. The Katsina Green Growth Agenda (KAGGA) is more than just a policy document, it is a transformative vision designed to align environmental resilience with economic growth.

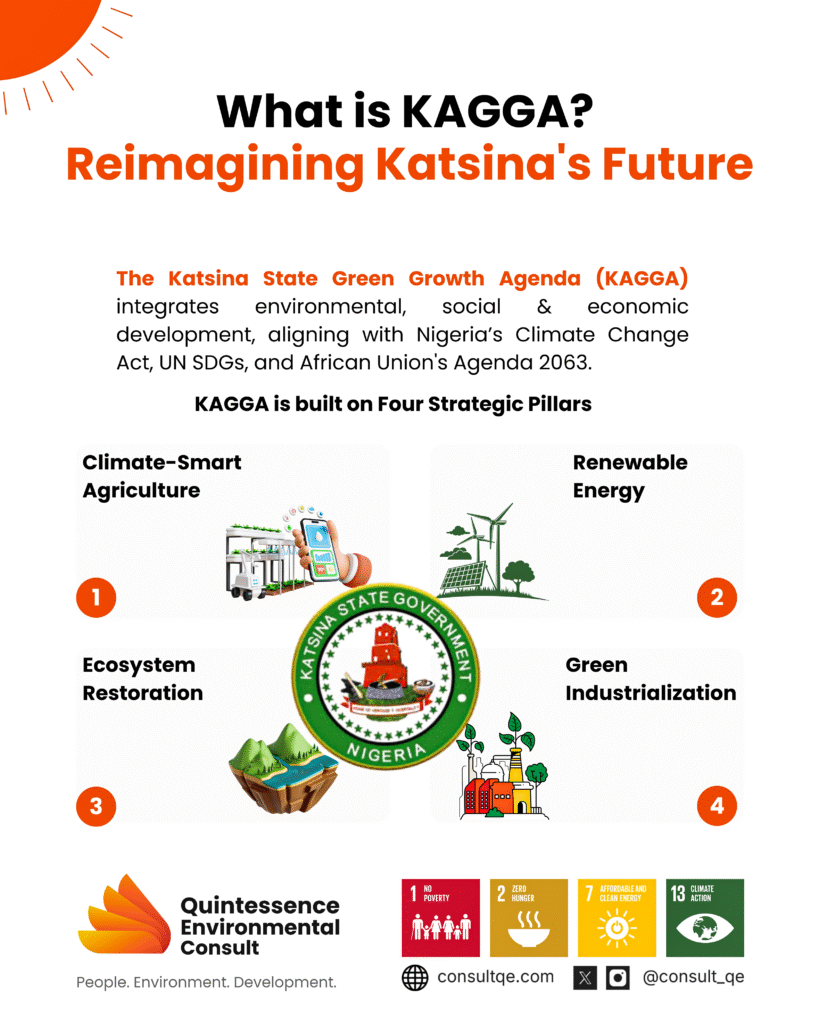

ICT as a Catalyst for Climate Action: Turning Bytes into a Better Planet

TAKEAWAY Technology fuels transformation: ICT is the catalyst behind innovations that are reshaping how we fight climate change across energy, agriculture, waste, and education. Real-time data saves real-world ecosystems: From satellites to sensors, ICT tools give us the intelligence we need to protect forests, track emissions, and predict disasters. Digital solutions are accelerating the green economy: Clean tech startups, green data centres, and digital agriculture are making sustainability profitable and scalable. ICT bridges the global climate knowledge gap: Online platforms are giving communities access to environmental data, resources, and training. The future of climate action is digital: As ICT continues to evolve, its potential to drive systemic climate solutions is just beginning. INTRODUCTION Can climate change be hacked? Not in the literal sense, but ICT is doing something close to it. From satellites mapping deforestation in real time to AI models predicting floods weeks in advance, technology is fast becoming our most powerful ally for climate change mitigation and adaptation. In a world where every second matters, ICT transforms awareness into action and data into decisions. It’s not just about fighting climate change, it’s about staying one step ahead. BACKGROUND Climate change is no longer a distant threat, it’s a present reality. Rising temperatures, shrinking glaciers, and increasingly violent storms are a wake-up call. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns that we have until 2030 to cut global emissions in half or risk irreversible damage [1]. But while the threat looms large, a powerful solution lies in our hands in the form of mobile phones, internet access, and digital infrastructure. Information and Communication Technology (ICT) includes everything from software and sensors to broadband and blockchain. According to the Global e-Sustainability Initiative (GeSI), ICT has the potential to reduce global CO₂ emissions by 20% by 2030, even though the sector contributes only about 2-3% of emissions itself [2]. This is a leverage point: When deployed strategically, ICT is not just part of the solution; it amplifies the solution. Tracking Environmental Challenges, One Pixel at a Time Technology allows us to see what was once invisible. Satellite systems operated by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (United States) (NASA), the European Space Agency (ESA), and private firms can now detect forest loss, melting ice caps, and methane (CH4) leaks from space. These are critical tools in shaping climate policy and enforcement. For instance, Global Forest Watch uses satellite data and Artificial Intelligence (AI) to monitor forests in real-time, alerting authorities of illegal logging within hours [3]. Meanwhile, the Environmental Insights Explorer by Google helps over 3,000 cities globally track building and transport emissions, helping mayors make data-driven climate decisions [4]. Without ICT, these insights would take months or never come at all. Smart Agriculture and Green Tech Agriculture, a major industry which emits greenhouse gases, is undergoing a digital revolution. ICT-powered tools such as precision farming, drone surveillance, and mobile weather forecasting are reducing input waste and increasing yields. In Kenya, applications like iCow and FarmDrive are helping smallholder farmers adapt to unpredictable weather by offering agricultural tips, weather updates, and access to microloans through mobile-based platforms. In India, sensors connected to the Internet of Things (IoT) are enabling farmers to control irrigation systems via SMS, conserving water while boosting food security. These solutions aren’t just reducing emissions, they are safeguarding our livelihoods and conserving the earth’s natural resources.. In the energy sector, smart grids are optimizing power distribution, cutting losses, and integrating renewables more efficiently. In fact, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), smart energy systems powered by ICT could reduce electricity waste by up to 30% by 2030, aligning with global aligning with global climate goals[5]. Digital Empowerment and Education for Climate Climate literacy is no longer limited to scientists. Through mobile apps, virtual classrooms, and gamified learning platforms, ICT is making environmental education accessible and engaging. Applications like Earth Hero and Klima turn climate action into a personal mission, helping users calculate, reduce, and offset their carbon footprints. UN CC: Learn offers free online courses that have educated over 500,000 learners globally on climate resilience, green jobs, and adaptation strategies [6]. In vulnerable communities, ICT is also vital for early disaster warning systems. Text-based alerts on floods, wildfires, and storms have saved thousands of lives in countries like Bangladesh and the Philippines. That’s the power of a single byte in protecting entire populations. ICT and Circular Economy Innovation ICT is the backbone of the emerging circular economy, an economic model focused on designing out waste and keeping resources in use. Smart inventory systems, blockchain-powered product tracking, and mobile platforms for sharing or reusing goods are helping consumers and businesses close the loop. Companies like Too Good To Go, used widely in European countries such as Denmark, France, United Kingdom and Germany, help reduce food waste by using mobile applications that let consumers buy unsold food from restaurants, bakeries, and supermarkets at a discounted price; instead of throwing away perfectly good food at the end of the day. These businesses list it on the application, and users can reserve and pick it up at a lower cost. This way, food that would have gone to waste gets eaten, helping both the environment and people looking for affordable meals. Startup companies like Loop which launched in the United States, France and the United Kingdom, use digital platforms to manage reusable packaging systems, allowing consumers to return and reuse branded containers instead of relying on single-use packaging. Blockchain, in particular, is enabling transparency in carbon trading, e-waste recycling, and ethical sourcing [7]. These technologies make sustainability measurable, accountable, and profitable. Youth, Climate, and Digital Advocacy Young people are leading the digital charge for climate justice. Social media platforms have become megaphones for international movements like Fridays for Future and Stop Ecocide. With nothing more than a smartphone, youth activists from Africa to Asia are organizing protests, sharing climate stories, and pressuring world leaders into action [8]. Additionally, platforms like Youth Climate Lab and Connect4Climate use digital storytelling and

The Environmental Cost Of Illegal And Unregulated Granite Quarrying In Nigeria

KEY TAKEAWAYS Illegal Granite Quarrying Is Environmentally Devastating: Unauthorized quarrying is responsible for widespread deforestation, air and water pollution, and irreversible land degradation across several Nigerian states. Health and Safety Risks Are Alarming: Unregulated granite extraction releases harmful dust (PM10), contributing to respiratory illnesses like asthma and sinusitis among nearby residents and quarry workers. Communities and Ecosystems Are Under Threat: Case studies from Abeokuta, Abuja, Edo, and Ebonyi reveal how quarrying disrupts ecosystems, reduces water quality, and destroys farmlands, threatening food security and biodiversity. Earth Tremors in Abuja Highlight Deeper Geotechnical Risks: The recent seismic activities in the Federal Capital Territory may be linked to unregulated blasting, underscoring the need for proper environmental and geological assessments. Sustainable Solutions and Community Action Are Urgently Needed: Stronger regulations, mandatory environmental impact assessments, rehabilitation of quarry sites, and active community engagement are essential to mitigate the environmental crisis. INTRODUCTION A quarry is a large, open excavation site on the earth’s surface where natural resources like stone/rock, gravel, sand, or minerals are extracted. Granite is a hard, coarse-grained igneous rock composed mainly of quartz, feldspar, and mica. It forms naturally when molten magma slowly cools and solidifies deep beneath the Earth’s surface. Granite quarrying is the process of extracting granite rock from the earth through open-pit mining methods. For many years, it has served as an important source of construction materials supply, employment and revenue, especially in developing countries like Nigeria, which are endowed with abundant granite deposits. Nigeria’s vast granite reserves have long fueled its construction and mining industries. From road construction to building skyscrapers, granite is an essential raw material. However, behind this booming industry lies a dark reality: illegal granite quarrying is wreaking havoc on the environment, leading to various impacts such as deforestation, soil erosion, water pollution, and air contamination. This article explores the environmental cost of illegal granite quarrying in Nigeria, shedding light on the consequences, key case studies, and the urgent need for sustainable mining practices. UNDERSTANDING ILLEGAL AND UNREGULATED GRANITE QUARRYING IN NIGERIA Illegal quarrying refers to the unauthorized extraction of granite without government approval, environmental impact assessments, and adherence to mining regulations. Many of these operations are run by small-scale miners or criminal syndicates, often exploiting rural communities for labour. The lack of oversight means these quarries operate recklessly, leading to widespread environmental degradation. Abeokuta city in Ogun State, for example, known for its abundant granite resources, is flourishing with illegal quarrying, which has caused significant health and environmental damage. A study by Oguntoke Olusegun (2009) shows that granite quarrying in Abeokuta has led to elevated levels of suspended particulate matter (PM10), posing serious health risks to nearby residents and quarry workers. Common issues include nasal infections, asthma, cough, and sinusitis. Similarly, in the Federal Capital Territory (Abuja) and its surrounding areas, rapid urbanization has increased demand for granite, leading to uncontrolled quarrying activities in areas such as Mpape 6, which threaten both the environment and local communities. Another example is granite quarrying in Edo North, Nigeria, where daily activities such as drilling, blasting, crushing, and transporting materials have a significant impact on the environment. These operations contribute to air and noise pollution, water contamination from runoff, and land degradation. With multiple active quarries per community, a study by Okolie K. C. 2021 confirms that quarrying practices have adverse environmental impacts. In Afikpo, Ebonyi State, the environmental impact of rock quarrying goes beyond just the physical destruction of the land. It also affects the quality of air and water in the area. The dust and debris from the quarrying process can contaminate the air and water, making them unsuitable for human consumption 3. ENVIRONMENTAL CONSEQUENCES OF ILLEGAL AND UNREGULATED GRANITE QUARRYING Deforestation and Habitat Loss Illegal quarrying often requires clearing large tracts of land, leading to deforestation. The loss of vegetation disrupts ecosystems, endangers wildlife, and contributes to climate change. A study by Adedeji et al. (2020) in Odeda, Ogun State, observed a significant decline in light forest cover from 637.28 hectares in 1984 to 326.52 hectares in 2014, attributed to quarrying activities. This represents nearly a 50% reduction over 30 years. Similarly, Akanwa et al. (2017) reported a 35.2% vegetation cover loss in Ivo Local Government Area, Ebonyi State, due to intensive quarrying operations. Soil Erosion and Land Degradation The process of quarrying begins with the removal of vegetation and topsoil. In legal operations, this is done with care and often includes plans for rehabilitation. However, illegal quarrying strips the land bare without any concern for restoration. Once the protective topsoil is gone, the land becomes exposed to wind and water erosion. This leads to the rapid washing away of soil nutrients essential for farming and biodiversity. Several communities have watched their fertile lands slowly transform into barren, rocky outcrops. Quarry pits are left open and untreated, turning into erosion channels and death traps. Rainfall accelerates this degradation, creating gullies and reducing the land’s capacity to support crops or vegetation. Water Pollution and Scarcity During quarrying, overburden removal, drilling, blasting, and rock crushing release large volumes of silt, dust, and chemicals into the environment. Without proper drainage or containment systems, runoff from quarry sites flows into nearby rivers, streams, and groundwater sources. This runoff carries fine particles, heavy metals, and sometimes explosive residues, which degrade water quality and harm aquatic ecosystems. In many rural communities that rely on surface and shallow groundwater for drinking, washing, and farming, this pollution leads to outbreaks of waterborne diseases, loss of fish populations, and reduced access to safe water. The disruption of natural drainage patterns also reduces groundwater recharge, intensifying water scarcity during dry seasons. Air Pollution and Public Health Risks One of the most visible effects of illegal quarrying is the release of large amounts of dust and particulate matter (PM10) into the air. This occurs during blasting, crushing, and the constant movement of heavy trucks. Without dust control systems like sprinklers or barriers, standard in regulated sites, these pollutants are freely dispersed into nearby communities. Residents

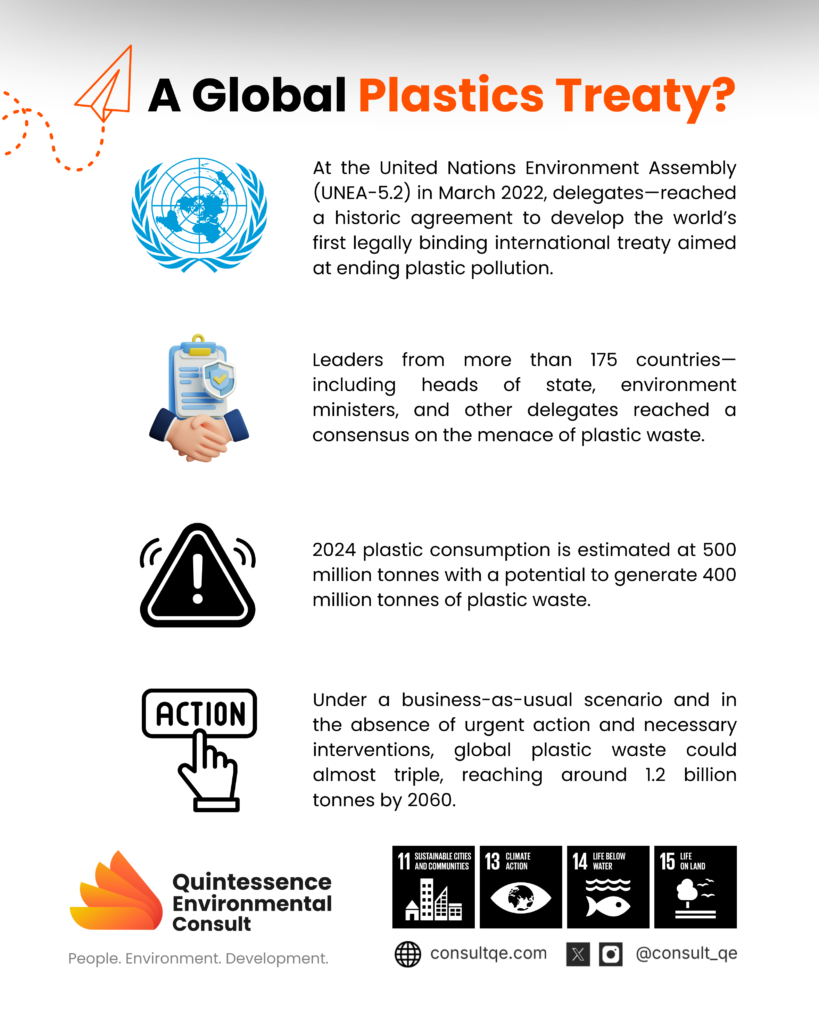

Understanding the Global Plastics Treaty

KEY TAKEAWAYS The Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) of the UNEP is developing a binding international framework for managing plastic waste. Significant progress has been made at the 5th meeting of the INC with proposals of a plastics production cap, clearing existing plastics, technology transfer and financing the provision of the proposal. Several challenges may hamper the success of the treaty when eventually ratified including conflict with business interests, political and policy priorities of member countries, and lack of power of enforcement over parties The national policy on plastic waste management proposed by Nigeria has provisions that are very much in line with those of the INC, showing that Nigeria is moving in the right direction. Sub-national governments in Nigeria may not see plastic waste as a priority issue and may require incentives to take action. INTRODUCTION Plastic waste accumulating in oceans, waterways, and landscapes has become a global challenge, causing harm to wildlife, ecosystems, and human health. The Plastic Treaty refers to a proposed Intergovernmental Legally Binding Instrument (ILBI) that seeks to tackle plastic pollution throughout its entire lifecycle, from production and consumption to waste management and disposal. The need for this treaty was raised in resolution 5/14 at the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) of the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) on March 2, 2022[1]. As of December 2022, 175 countries have joined the negotiation process on the Treaty. The treaty is to be drafted by the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee(INC), convened by the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP), taking into account the principles of the Rio Declaration but with differentiated responsibility to individual nations’ circumstances and capabilities. The fifth and supposed final session of the INC (INC-5.1) took place in Busan, South Korea, in November 2024, but it ended without an agreement. A second part of the 5th session (INC-5.2) is scheduled for August 2025 in Geneva, Switzerland[2]. The treaty, when finally agreed upon and judiciously implemented by member countries, is expected to reduce Plastic Production, Consumption and disposal, promote sustainable Waste Management practices, Recycling, and support Research and Innovation. The proposed plastic treaty includes 32 articles, some of which offer a framework for ratification, documentation, and implementation, while others address core issues of plastic waste, such as plastic production caps, existing plastic waste, and improvement of plastic design and its alternative materials. The implementation seeks to preserve the economic development of the parties, not disrupt international trade, protect local customs, and cultural heritage. The implementation of the treaty will be monitored and regulated by a conference of parties Some of these core issues are elaborated further on below. Plastic production Caps and alternatives: According to Article 3 of the proposed treaty, member countries are to end the production and consumption of certain categories of plastics listed in Annex X and Y after a yet to be agreed upon date but after 2030. These products include single-use plastics and plastics containing certain toxic compounds, including DEHP (CAS number 117-81-7), DBP (CAS number 84-74-2), BBP (CAS number 85-68-7) and IBP (CAS number 84-69-5), as well as children’s toys containing heavy metals, such as lead and chromium. Article 4 allows member countries, according to their respective socioeconomic goals, to seek to delay enforcement of the ban not later than 5 years after the stipulated dates. Articles 5 and 6 proposed research into better design and sustainable alternatives to plastic to ensure circular economy practices[3]. Waste management: Articles 7 to 9 focus on waste management, including guidance against the leakage of plastic waste into unregulated systems as well as dealing with existing plastic waste. It emphasized the primacy of the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes. Member countries are encouraged to set targets to increase the collection and recycling rates of plastic waste, identify plastic accumulation zones and engage in joint clean-up campaigns, especially for transboundary waste.[3] Technology transfer and Financing mechanism: The treaty’s success depends on robust technology transfer and adequate financing. As the developed countries have generally contributed disproportionately to the plastic problem, they equally bear a disproportionate burden of the financial commitment. Developed parties are expected to fund the treaty through primary plastic polymer fees, extended producer responsibility schemes, development strategies, bilateral & multilateral funding, private sector investment, voluntary contributions, and national budgets. The fund (Global Environment Facility Trust Fund) will be managed by the conference of parties. Priority of access is given to the most vulnerable countries, such as least developed countries (LDCs), landlocked nations, small island developing states (SIDS), lower riparian countries and archipelagic states[3]. POTENTIAL THREAT TO THE GLOBAL IMPLEMENTATION OF THE TREATY Conflict with business interests: Business interests may clash with the implementation of the treaty, as many industries depend on plastic products for packaging, manufacturing, and consumer goods. The economic interests of these industries could directly conflict with the treaty’s regulations, especially Article 3, which calls for a ban on the production and consumption of specific types of plastics. Diverse government Priorities: Government priorities can shift due to local politics, preventing parties from meeting their commitments. A clear example of this is the current U.S. president, Donald Trump. Since taking office, he has withdrawn from several multilateral agreements[4], including the climate change agreement, and has expressed his opposition to the plastic treaty. He also reversed the ban on plastic straws in place before his presidency [5]. Such actions from the president pose a significant threat to the success of the treaty. Moreover, countries experience varying levels of plastic pollution, making it difficult to create a global treaty that is fair and equitable for both developed and developing nations. This fear exists despite the financial obligations the treaty imposes on developed countries. This disparity partly contributed to the inability of members to reach an agreement during the recent INC meeting in Busan, South Korea. Implementation and Enforcement: The proposed treaty provides guidelines to help countries adhere to its provisions, but there are no mechanisms in place to force sovereign nations to comply if they fail to do so. Additionally,

The global standards for WASH: Are We Meeting Them in the Federal Capital Territory’s (FCT) Primary Healthcare Facilities?

Takeaways WASH Deficiencies in FCT Healthcare Facilities: Many primary healthcare centers (PHCs) in Nigeria’s Federal Capital Territory (FCT) lack essential water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services, leading to compromised infection prevention and control. Global WASH Standards: The World Health Organization’s Joint Monitoring Programme outlines service ladders for drinking water, sanitation, and handwashing facilities, ranging from “safely managed” to “open defecation,” to assess and improve WASH services. Impact on Health Outcomes: Inadequate WASH facilities in healthcare settings contribute to higher rates of healthcare-associated infections, including neonatal and maternal infections, adversely affecting patient outcomes. Initiatives for Improvement: Organizations like UNICEF and WaterAid are working to enhance WASH infrastructure in Nigerian healthcare facilities, including the FCT, through the construction of solar-powered boreholes and advocacy for better hygiene practices. Call to Action – Increased funding and coordination by relevant government agencies. INTRODUCTION Did you know that some primary healthcare facilities in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Nigeria, still lack access to basic water and sanitation services? Patients and healthcare workers often struggle with poor hygiene conditions, leading to increased risks of infections and disease outbreaks. With global benchmarks for Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) being essential for quality healthcare, this blog explores whether primary healthcare facilities in Nigeria’s Federal Capital meet these basics. BACKGROUND – What is WASH? WASH stands for Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene. These components are essential for preventing infections and ensuring the health and safety of individuals in any setting—especially in healthcare facilities. Accordingly, global standards for WASH services have been defined to establish accessibility and inclusion for all. The WASH framework has evolved significantly over the past few decades. Originating in the early 1990s, the initiative was initially driven by the urgent need to combat waterborne diseases and poor sanitation. Global agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) set forth comprehensive standards that focus on: Ensuring safe drinking water: Meeting quality standards through parameters like pH, turbidity, total coliform counts, E. coli, and other contaminants. Providing adequate sanitation: Including properly maintained toilets and waste management systems. Promoting effective hygiene practices: Access to handwashing facilities, sterilization protocols, proper maintenance and waste management practices. The JMP Standard For WASH Services The Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) by WHO and UNICEF defines WASH standards using a service ladder approach to assess access to water, sanitation, and hygiene. It categorizes services into five levels: Safely Managed, Basic, Limited, Unimproved, and No Service, providing a structured framework for global monitoring. Drinking Water Sanitation Hand Washing Safely managed Safely managed Basic Basic Basic Limited Limited Limited Unimproved Unimproved No facility Surface Water Open defecation Drinking Water Safely managed Drinking water from an improved source, located on premises, available when needed, and free from contamination. Basic Drinking water from an improved source, but requiring less than 30 minutes (round trip) to collect. Limited Drinking water from an improved source, but collection time is more than 30 minutes (round trip). Unimproved Drinking water from an unprotected well or spring. Surface Water Drinking water collected directly from rivers, lakes, ponds, or streams. Sanitation Safely Managed Use of improved sanitation facilities, not shared, with safe disposal or treatment of waste. Basic Use of improved sanitation facilities, not shared with other households. Limited Use of improved sanitation facilities, but shared with other households. Unimproved Use of pit latrines without slabs, hanging latrines, or bucket latrines. Open Defecation Disposal of feces in fields, bushes, or open spaces. Hand washing Basic Handwashing facility with water and soap available at home. Limited Handwashing facility without soap or water. No Service No handwashing facility available at home. WASH services aim to provide sustainable solutions to improve living conditions, reduce poverty, and ensure universal access to water and sanitation by 2030. Beyond its direct impact on health outcomes, inadequate WASH services contribute to broader social and economic challenges. The high burden of preventable diseases due to poor WASH conditions leads to increased healthcare costs and adverse economic outcomes for communities. GLOBAL AND NIGERIA’S CASE STUDIES IN WASH IMPLEMENTATION Global Case Studies Sato Pan Introduction: Launched in Bangladesh in 2012, the Sato Pan is an innovative toilet solution designed for low-income communities. Its counterweighted trapdoor minimizes insect and odor exposure while using less than one liter per flush. By 2014, over 800,000 units had been installed, and the initiative had expanded to 45 countries, benefiting over 68 million people. WASH FIT Implementation: The Water and Sanitation for Health Facility Improvement Tool (WASH FIT) has been adopted in countries like the Philippines, Indonesia, Kenya, and Mali. This tool enhances WASH services in healthcare facilities, leading to improved patient outcomes and facility hygiene standards. Nigerian Case Studies In Nigeria, access to WASH services remains challenging. According to WASHNORM (2021), approximately 67% of the population has access to basic water supply services, but only 13% are classified as “safely managed.” There are approximately 33,000 Primary healthcare Care (PHC) facilities, but half of them lack clean water, and 88% lack basic sanitation amenities; FCT is no exception. Several organizations, including WHO, UNICEF, and local Non-governmental organizations (NGOs), are working to improve WASH facilities in Nigeria. These include: 2 1. UNICEF, in collaboration with the Nigerian government, has constructed and rehabilitated over 1,700 solar-powered boreholes across multiple states, including the FCT. Examples of these are: Benue State Uikpam IDP Camp: In November 2021, UNICEF commenced the construction of a 12,000-litre motorized solar-powered water borehole, along with two blocks of five-compartment toilets and five-compartment bathrooms, to serve approximately 27,227 Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in the Uikpam IDP camp, Guma Local Government Area.8 Kano State Fadisonka Community: In Fadisonka, Wudil Local Government Area, a solar-powered borehole was installed around 2013 by the Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Agency in partnership with USAID and UNICEF. This borehole serves as the primary water source for the community.9 2. Programs like the WaterAid Nigeria’s Hygiene for Health campaign have played a crucial role in promoting proper sanitation and hygiene within PHCs, contributing to improved patient safety.