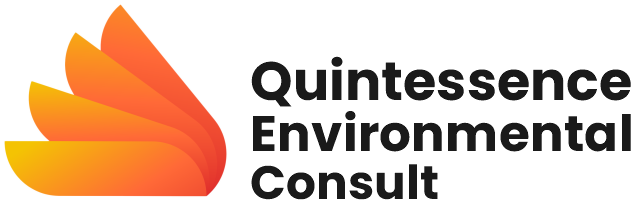

Reforming Nigeria’s Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining Sector: A Path to Sustainable Livelihoods

deposits of Plateau, Bauchi, and Kano, and the gemstone markets of Kaduna, ASM provides livelihoods where farming or other jobs are limited.

However, this lifeline comes with paradoxes. While ASM reduces rural poverty, supports households, and contributes to mineral output, it is also plagued by informality, unsafe practices, environmental degradation, and lost government revenue. Nigeria faces a crucial choice: continue to allow ASM to operate in the shadows, or reform it into a pillar of sustainable livelihoods and responsible mining.

The sector remains underdeveloped despite Nigeria’s mineral wealth across more than 500 locations in the 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). The Nigerian Mining Corporation, once a leading producer, declined after the 1970s indigenization policy, and now contributes 4.38 per cent to the overall GDP in the first quarter of 2025, lower than the 5.47 per cent contribution recorded in the same quarter of 2024, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) latest GDP report.[14]

The underperformance stems largely from ASM-related challenges, including informality, weak regulatory oversight, insecurity, smuggling, and under-declaration of exported minerals.

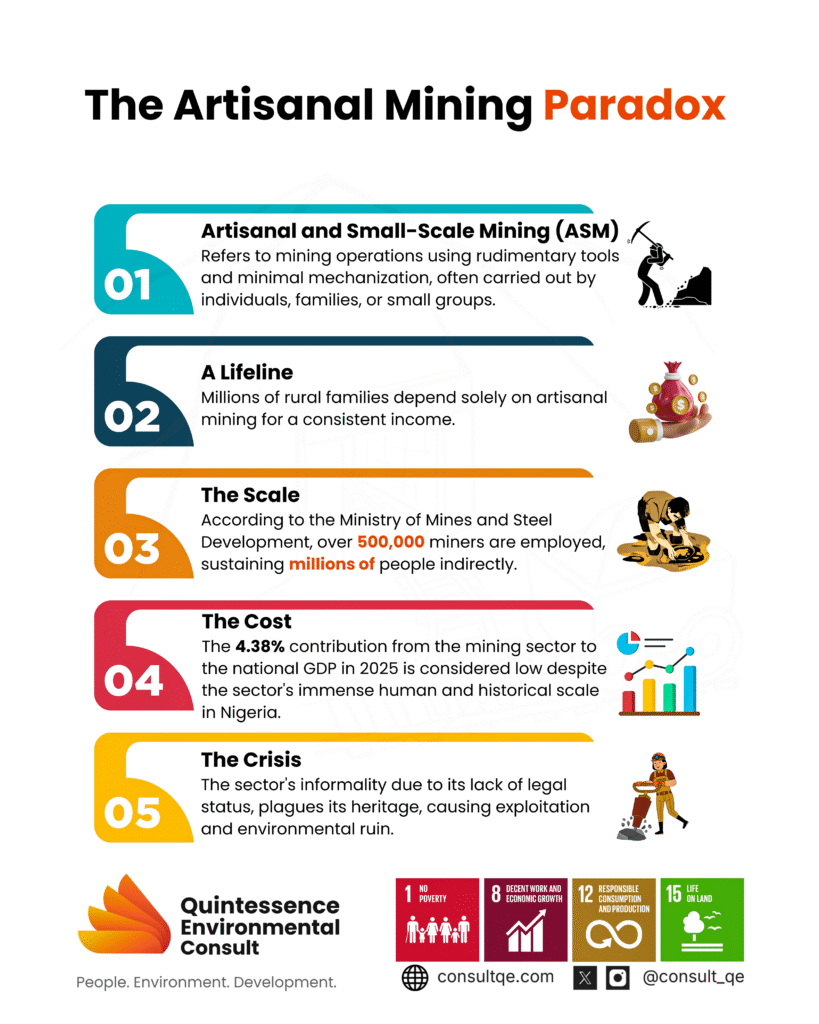

Tyre Upcycling: Turning Waste into Circular Value

Every year, billions of tyres are manufactured, serving a vital role in transportation across the globe. However, once these tyres reach the end of their life, they pose a significant environmental challenge. Their durability and non-biodegradable nature cause them to accumulate in landfills or scrapyards, contributing to pollution through leaching of harmful chemicals, fire hazards, and the creation of breeding grounds for disease-carrying pests.

Tyres are highly engineered composites made from a blend of materials designed to ensure strength, flexibility, and durability. On average, they consist of 10–40% natural rubber for elasticity, 20–60% synthetic rubber (such as styrene-butadiene and butadiene rubber) for abrasion resistance, 15–30% carbon black or silica as reinforcing fillers, 10–15% steel for structural support in belts and beads, and 3–8% textile fibres such as nylon, polyester, or rayon for stability.

In addition, 5–10% chemical additives (including sulphur for vulcanization, oils, antioxidants, and resins) are incorporated to enhance resistance to heat, oxidation, and UV degradation. These components work together to create tyres that can withstand heavy loads, high temperatures, and constant friction, making them critical to modern transport systems.

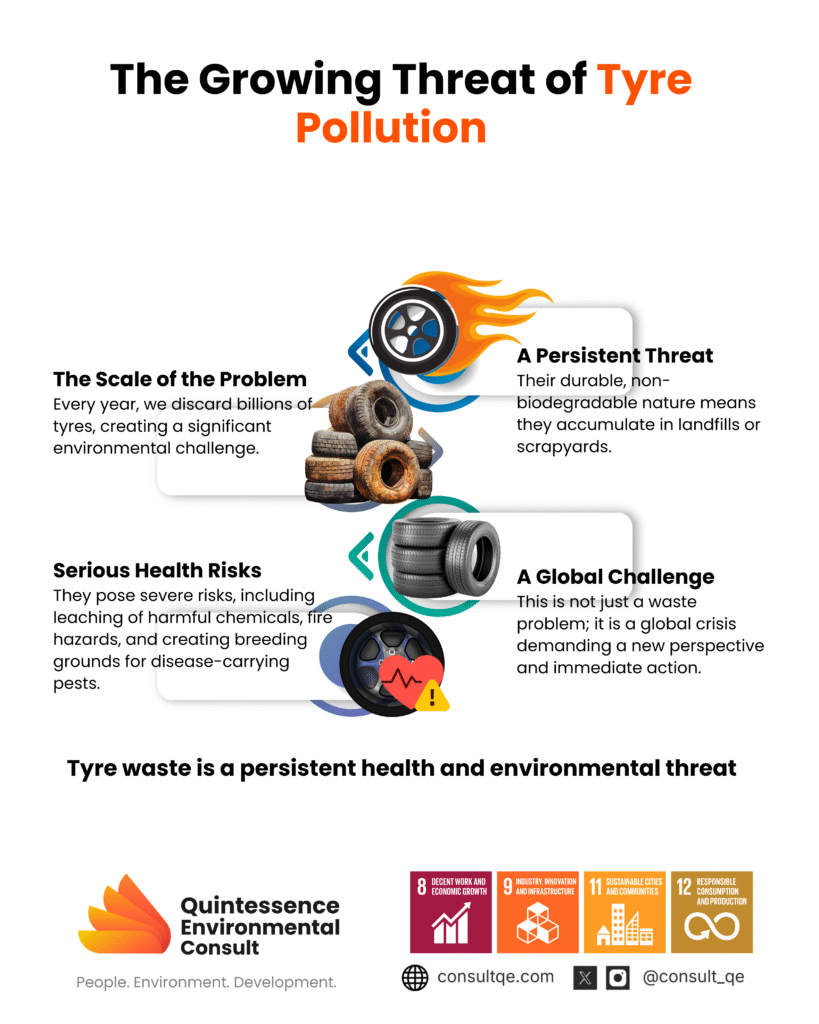

Environmental Impact Of Plastic Additives In Nigeria: An Emerging And Overlooked Contaminant Of Concern

Plastic products often contain additives such as plasticizers, stabilizers, flame retardants, pigments, PFAS-based coatings, and biocides, which are incorporated into polymer matrices to enhance their performance. Since most of these additives are not chemically bonded to the polymers, they can leach out, evaporate, or be released along with micro- and nanoplastics into the environment.

While global concern about this chemical aspect of plastic pollution is increasing, in Nigeria—where plastic waste management faces challenges like high waste production, limited formal recycling, open dumping, and frequent flooding—these additives remain a largely overlooked but potentially significant source of environmental contamination (Ebere et al., 2019; Faleti, 2022).

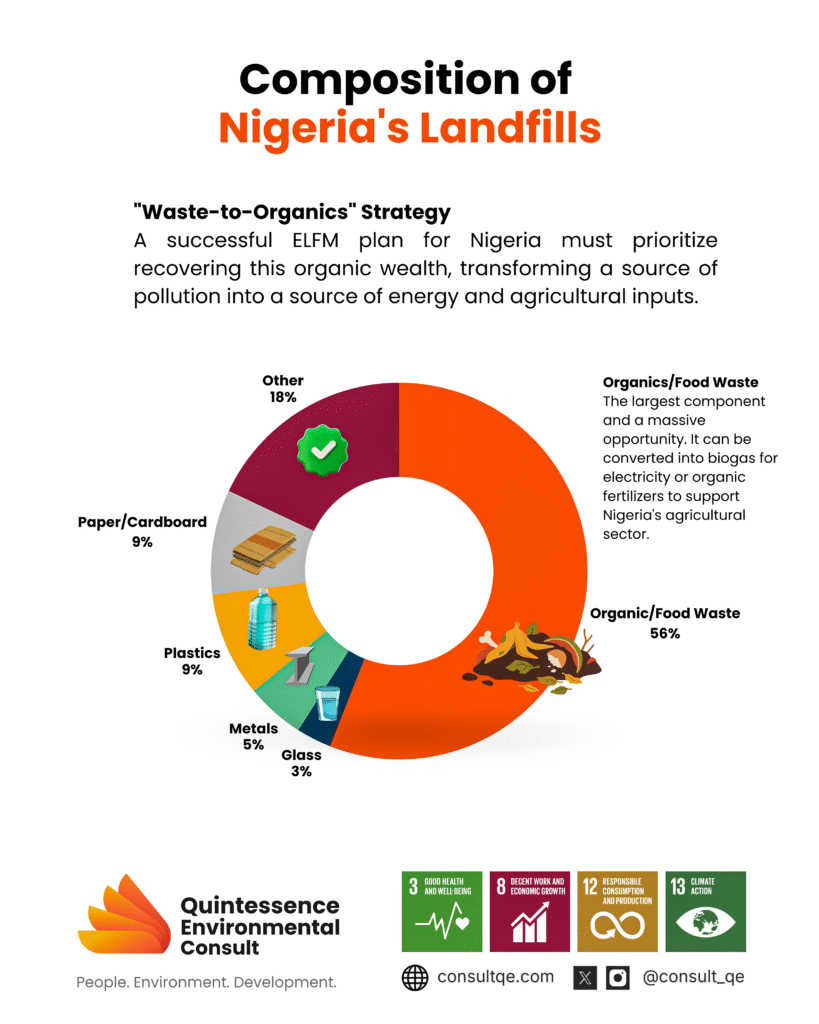

Landfill Mining in Nigeria: From Dumpsites to Green Economy

For decades, landfills have been a quick, out-of-sight solution for our ever-growing piles of garbage. They’re often seen as the most economical way to deal with waste, but they come with significant environmental liabilities. Despite the global push for recycling, landfilling remains a dominant practice in many developing nations like Nigeria, leaving countless dumps full of accumulated waste, including valuable materials that are simply buried.

Landfill mining is the process of excavating closed or active landfills to recover valuable resources, reclaim land, and mitigate environmental hazards. Unlike traditional waste management, which focuses on handling new waste, landfill mining goes back to the existing landfill to reclaim a treasure trove of recyclable and reusable resources such as metals, plastics, and glass. 5

This reduces the need for virgin materials and supports a circular economy.

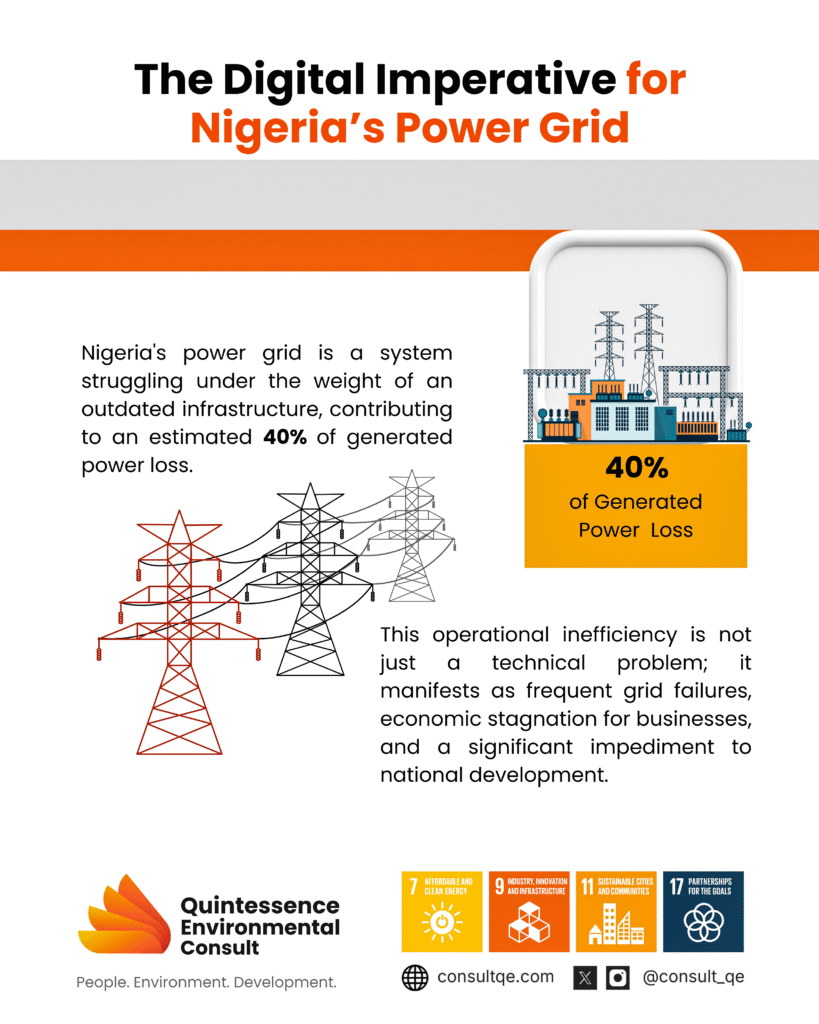

Beyond Smart Grids: Unpacking the Next Wave of Digitalization in Nigeria’s Energy Sector

Nigeria stands at a pivotal moment in its energy transition. While the conversation around smart grids has laid a crucial foundation, the next wave of digitalization promises even more profound transformations. We are talking about a future where Artificial Intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), blockchain, digital twins, and edge computing converge to create an energy ecosystem that is not just smart, but also predictive, resilient, and highly efficient. As Nigeria grapples with the dual challenge of expanding energy access and ensuring sustainability, these advanced digital tools are no longer futuristic concepts but essential enablers for progress.

This evolution is about using deeper intelligence to solve persistent problems, such as high energy losses and grid instability, and unlocking new opportunities for consumers and the economy.