Decarbonizing The Nigerian Built Environment Through Engineered Local Materials

INTRODUCTION

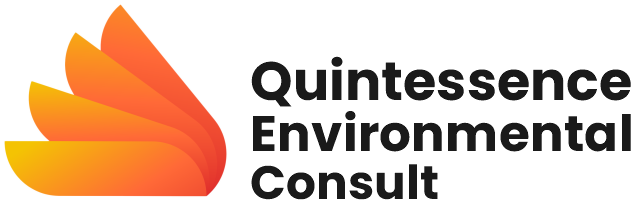

The necessity for a shift in the Nigerian construction industry is driven by dual and intersecting crises: the enormous national housing deficit and the growing environmental urgency for sustainability. Rapid urbanization has pushed formal housing costs to extremes, effectively pricing millions of citizens out of the market (11). This crisis is exacerbated by the sector’s persistent reliance on imported, carbon-driven models such as steel & cement production, which are detrimental to low-cost housing goals and increase the nation’s carbon footprint (27). Integrating low-carbon, culturally resonant materials is therefore vital for achieving economic stability, social inclusion, and ecological sustainability

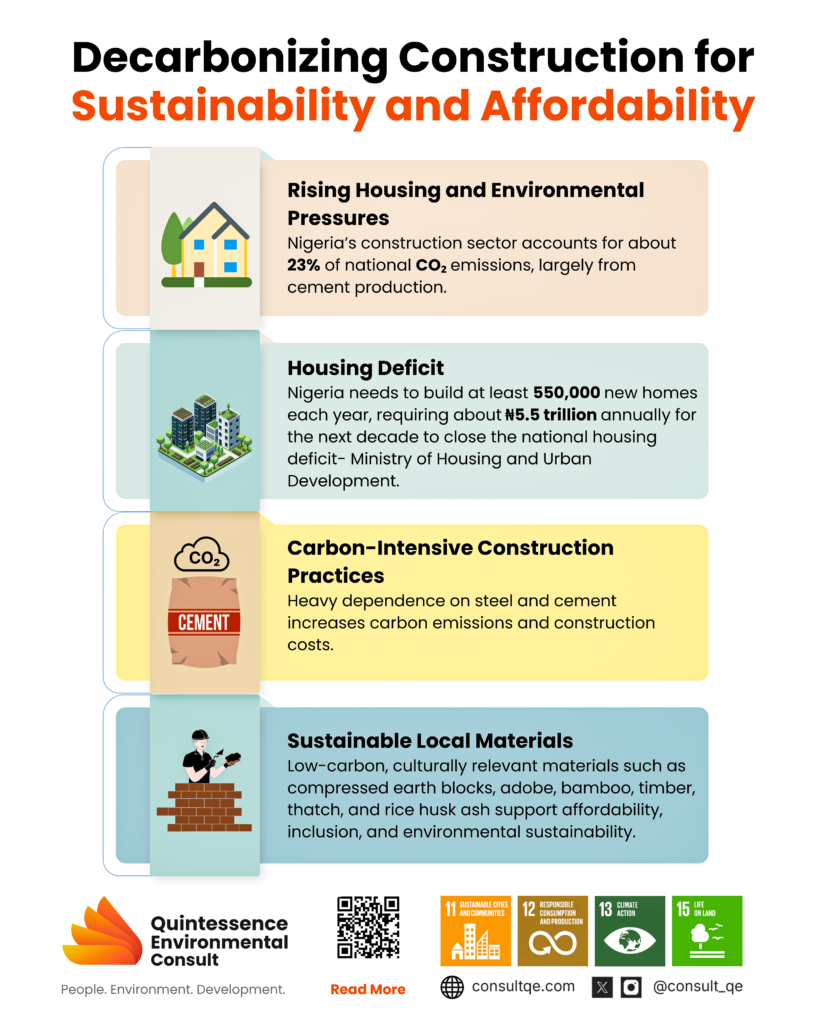

Connected But Costly: The Environmental Footprint Of A Digital World

The global Information Technology (IT) ecosystem is often perceived as a realm of dematerialization, a transition to intangible data streams that leave no physical trace. This perception, however, masks a profound and destructive physical reality. The massive, interconnected infrastructure that supports our digital world, from colossal data centers to specialized Artificial Intelligence (AI) chips, is constructed upon a foundation of intense resource extraction, astronomical energy demand, and persistent environmental debt .

This defines a critical paradox: the very technology designed to connect and advance human civilization is accelerating planetary collapse by becoming a primary driver of biodiversity loss and contamination of soils, waterways, air, and even living organisms through toxic mining waste, chemical leaching, and persistent e-pollutants.

Why The Global Plastics Treaty Failed and What it Means for Nigeria

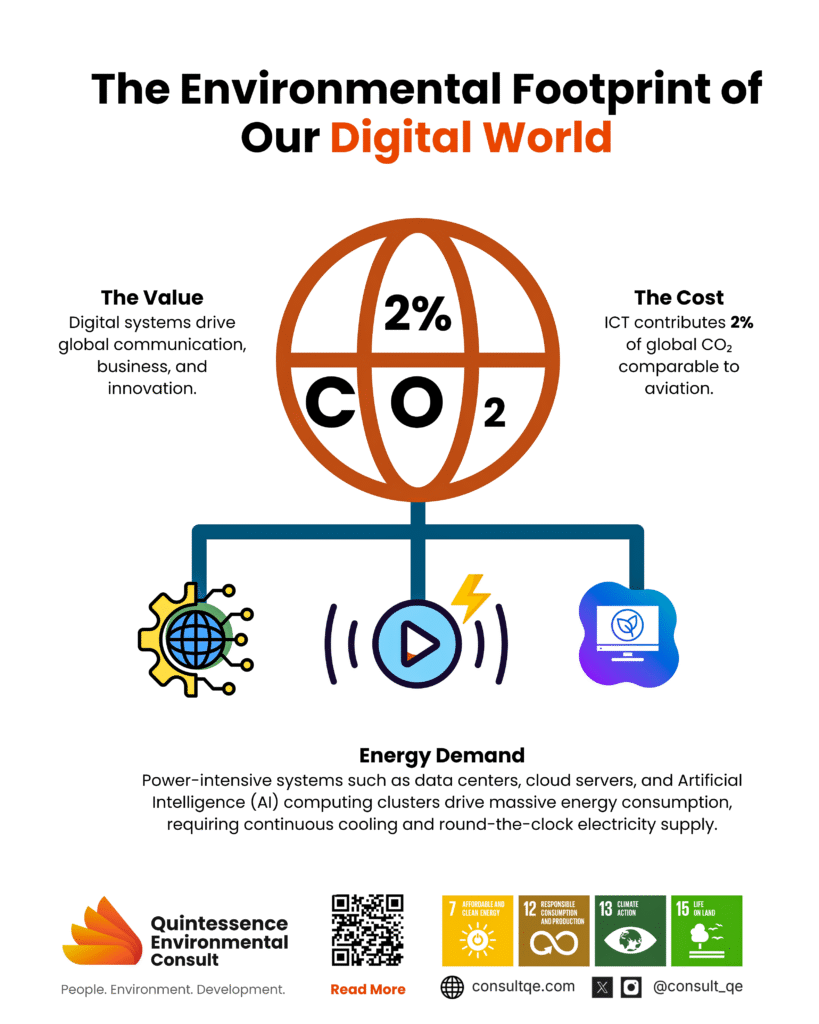

Each year, the world produces over 400 million tonnes of new plastic. In the absence of significant policy reforms, this figure is projected to increase by nearly 70% by 2040, according to a 2024 OECD policy scenario report8. The proposed Global Plastic Treaty aims to address plastic pollution across its entire lifecycle, covering production, consumption, waste management, and disposal. In addition, the treaty is expected to provide funding and technology transfer to support plastic waste management.

Formal negotiations on the treaty were led by the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC), which commenced in December 2022, with representatives from 175 countries participating. In addition, major financial institutions were expected to play a key role in promoting the development and implementation of the treaty within the global financial sector5. However, following the final round of talks (INC-5.2)7, held in August 2025 in Geneva, Switzerland, the Committee failed to reach a unified position. The breakdown of these negotiations has left the international community without a comprehensive, legally binding framework to effectively tackle the escalating plastic pollution crisis. A major impediment to progress was the INC’s reliance on consensus-based decision-making—a diplomatic mechanism that enables individual delegations to delay or obstruct collective outcomes. Attempts to reform this approach, including proposals for qualified majority voting in specific contexts, proved politically contentious and ultimately unsuccessful. Consequently, a small number of dissenting states were able to stall the entire negotiation process. This paper explores the main factors contributing to the negotiation deadlock and assesses the broader implications for Nigeria, one of Africa’s largest producers of plastic waste.

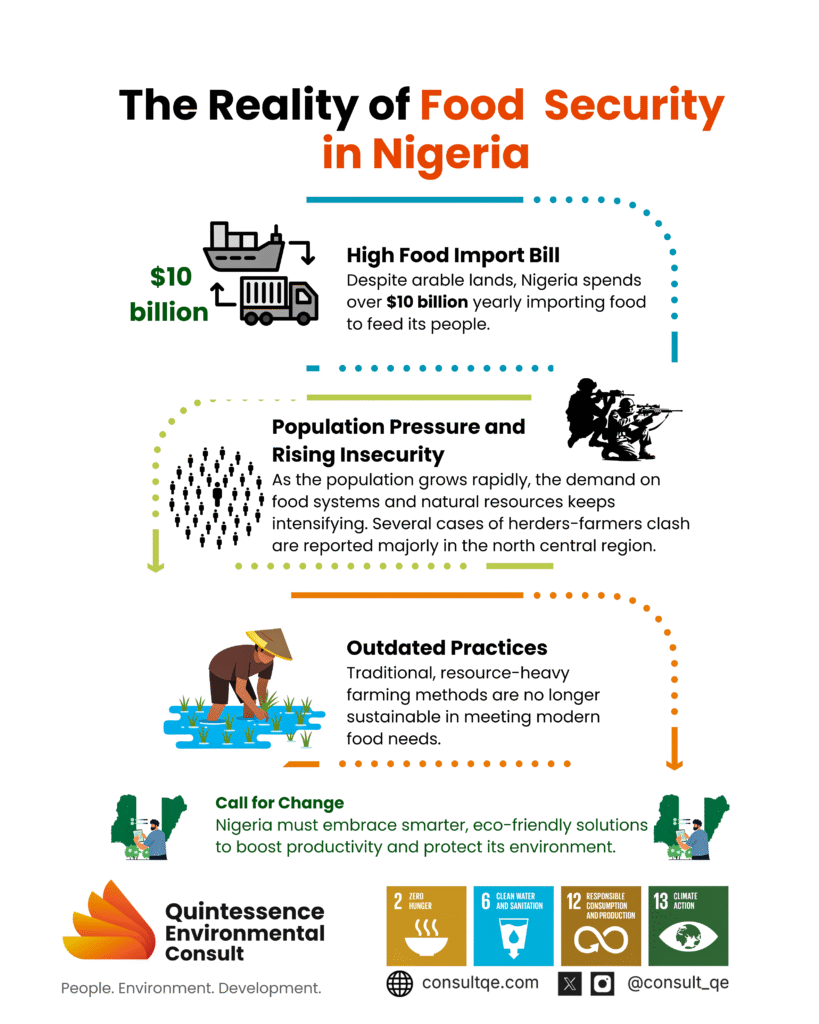

Precision Agriculture for Sustainable Food Security in Nigeria

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, stands at a critical juncture where a rapidly increasing population meets the urgent need for enhanced food security and sustainable agricultural practices. Nigeria currently spends over $10 billion annually on food imports, despite its vast agricultural potential, highlighting a significant production gap [9]. The conventional, often resource-intensive farming methods, particularly those used by the smallholder farmers, are no longer sufficient to meet soaring food demand while mitigating environmental impact. Precision agriculture, also known as smart farming, directly addresses this by optimizing growing conditions.

WHAT IS PRECISION AGRICULTURE?

Gone are the days when farming was purely about intuition and experience. Modern agriculture is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by an array of sophisticated technologies. This is not just about bigger tractors; it is about smarter farming, managing every inch of your land with unprecedented accuracy and efficiency. Welcome to the world of Precision Agriculture (PA), where data is the new harvest.

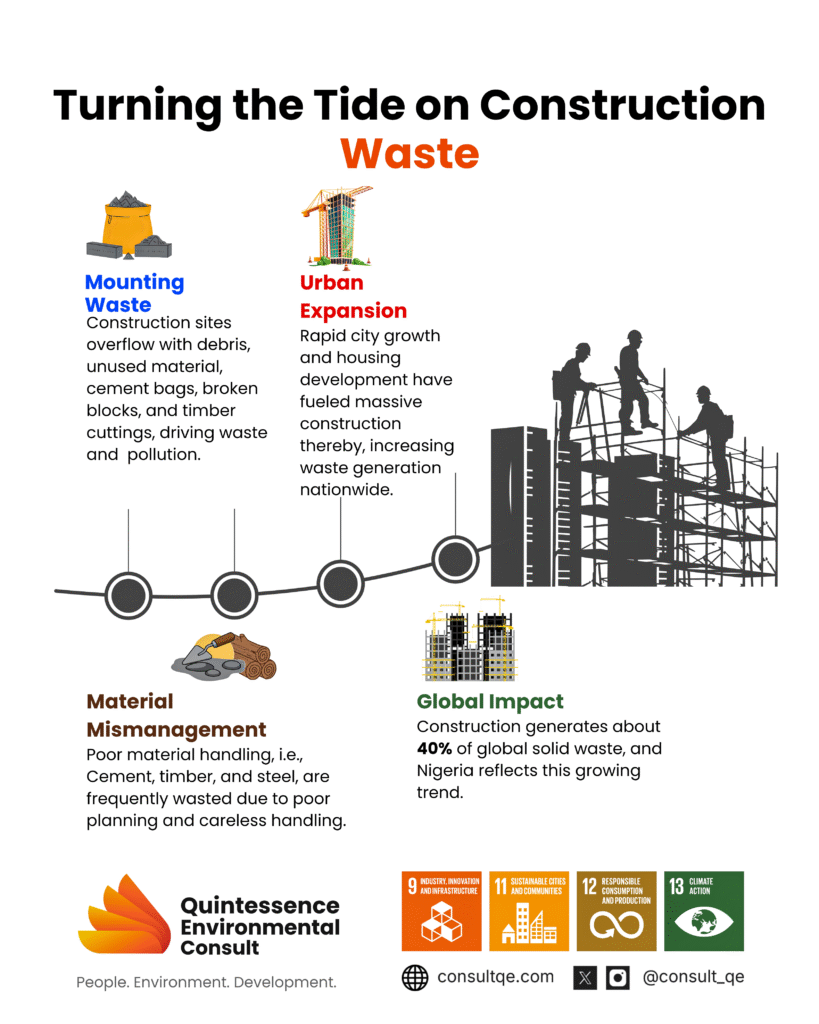

Building Smarter, Wasting Less: The Future of Sustainable Construction in Nigeria

INTRODUCTION

Imagine a building site where piles of cement bags, broken blocks, and timber cuttings grow higher than the house being built. This is the reality of many construction sites in Nigeria today. The waste generated not only drives up project costs but also pollutes the environment, worsening the housing crisis and undermining sustainable development. Nigeria is one of the fastest-urbanizing countries in Africa. According to the United Nations, more than half of Nigerians now live in cities, and by 2050, the urban population is expected to double (United Nations, 2019). This urban expansion has fueled a construction boom, with roads, housing estates, and commercial buildings springing up in almost every state. While this growth supports economic development, it has created a hidden challenge: the massive generation of construction waste.

Cement is Nigeria’s most commonly used building material, with annual consumption exceeding 20 million metric tons (Nigerian Bureau of Statistics, 2020). Yet at construction sites, it is common to see cement wasted during mixing, hardened leftovers dumped after setting, and bags spoiled by moisture before use. Timber, another widely used material, is often cut to sizes that leave large offcuts, while broken blocks and bent reinforcement rods are discarded without reuse.

This careless material culture contributes to high construction costs and environmental degradation.

Globally, the construction industry accounts for about 40% of solid waste generation (United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP], 2021). Though Nigeria lacks comprehensive national data, anecdotal evidence suggests construction waste is one of the largest contributors to solid waste in cities like Lagos and Abuja. Unless addressed, this problem will worsen as demand for housing and infrastructure grows.