Nature-based Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation: How Nigeria Can Build a Greener, Safer Future with Nature’s Help

From the submerged streets of Victoria Island during a downpour to the blistering, sun-baked landscapes of the Sahelian north, Nigeria is on the front lines of a climate crisis. So far, rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and increased frequency of flooding have disrupted many lives and exacerbated existing vulnerabilities and conflicts, jeopardizing the country’s socio-economic stability.

CARBON MARKET ECOSYSTEM: SOMETHING FOR EVERYONE!

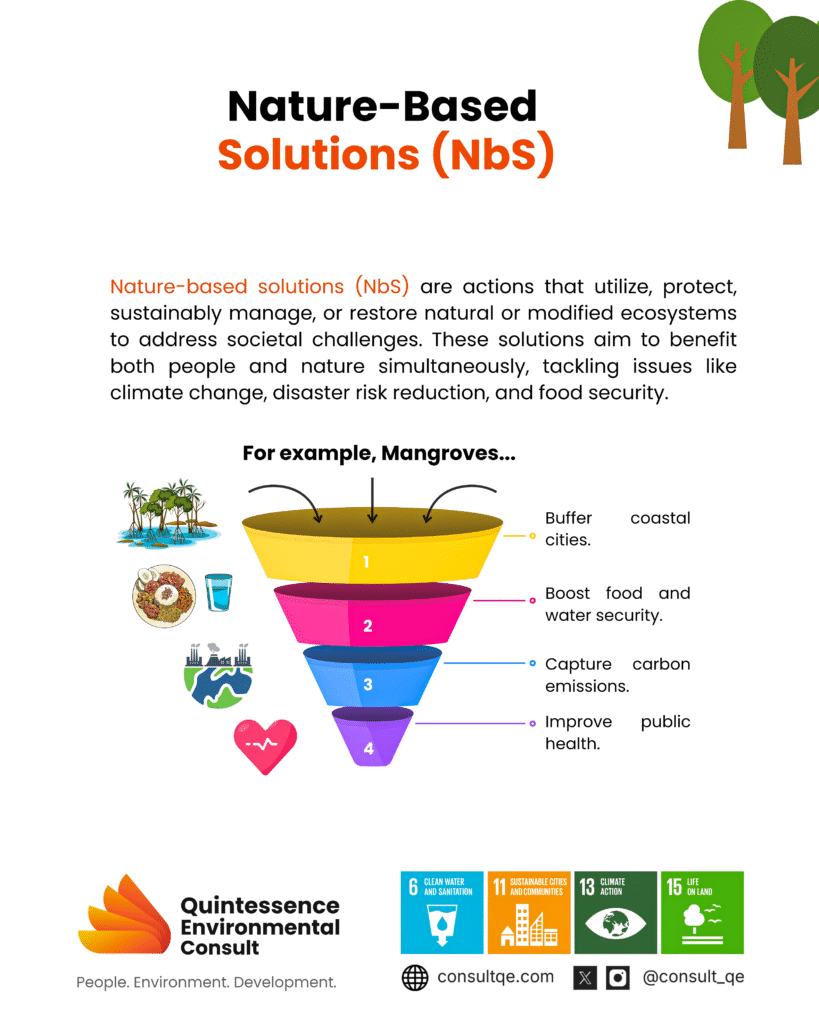

KEY TAKEAWAYS Nigeria’s carbon market potential is estimated at 87.2 to 124.7 million metric tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) from reduction or removal projects. The cumulative potential market value is projected to be between 736 million USD and 2.5 billion USD by 2030. Despite wide challenges in setting up and operationalizing a carbon market system, several opportunities for advancement abound for various stakeholders through participation, collaboration and commercialization of services. The carbon market supports innovative climate adaptation projects, fostering research and innovation. Governments, companies, and individuals can actively participate in the carbon market system as either regulators, project developers, investors, researchers, carbon removal monitors and others. INTRODUCTION Nigeria has a carbon market potential of 87.2 to 124.7 MtCO2e (metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent) that could be achieved from removal or reduction projects. In addition, Nigeria’s cumulative carbon market potential value stands between 736 million and 2.5 billion USD by 2030. But what exactly is the carbon market and what role can you play in it? The carbon market ecosystem is a market-based system that promotes the trade of carbon credits to incentivize the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. The idea is to create a market system that advances global efforts to reduce GHG emissions. These emissions are generally quantified into carbon credits, which can be bought and sold. The metric for measurement is that one tradable carbon is equivalent to one metric tonne of CO2 or other greenhouse gases that are reduced, sequestered or avoided. Effectively, a carbon credit is an emission permit for a specified amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) or other greenhouse gases (GHGs). For every one credit, you can release into the atmosphere one metric ton (2204 pounds) of CO2 or an equivalent amount of another GHG. Carbon credits can be purchased by countries as part of their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) strategy, by corporations with sustainability targets, and by private individuals looking to compensate for their carbon footprint. Another means of promoting emission reductions is through carbon offsetting. Unlike carbon credits (which represent a “cap” on permissible emissions), carbon offsets represent emissions that have been “removed” from the atmosphere, either through natural sequestration or technological reduction projects. From a regulatory standpoint, there is no use case for purchasing carbon offsets from a voluntary market. However, this does not mean they are not useful or valuable; they may, after all, increase in value making them an interesting, emerging asset class. EMISSIONS TRADING AND CARBON MARKETS Carbon markets are a carbon pricing mechanism, facilitating State and non-State actors to trade greenhouse gas emissions. The carbon market initiative aims to drive climate action targets and facilitate cost-effective climate transition programs. The carbon market scheme is classified into two categories namely; The Regulatory Compliance Market The compliance market otherwise known as the compliance carbon market (RCM) is used by companies and governments that are legally required to account for their GHG emissions. It is regulated by mandatory national, regional or international carbon reduction regimes. Accordingly, in compliance markets such as national or regional emissions trading systems (ETS) participants act in response to an obligation established by a regulatory body. The CCM primarily works based on a cap-and-trade system regulated by the Government, setting a specific cap on emissions in a particular region or sector. The Voluntary Market In voluntary carbon markets (VCM), there is no binding obligation on participants such as companies or individuals, but these non-State actors seek to offset their emissions voluntarily. The VCM is driven by the recognition that national commitments to cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to meet the requirements of the Paris Agreement of limiting global warming to 1.50 C and no more than 2.00 C is not promising. Key Components of the Carbon Market Project Developers: These entities create projects that reduce or sequester GHGs, such as reforestation, renewable energy, or energy efficiency projects. Verification and Certification: Independent third parties verify and certify that the projects are indeed reducing GHGs and issue carbon credits accordingly. Registries: Carbon registries track the issuance, ownership, and retirement of carbon credits. They provide transparency and prevent double counting of emission reductions. Carbon Credit Buyers: These include companies and individuals who purchase carbon credits to offset their emissions. They can be part of mandatory compliance markets or voluntary markets. For instance, international airline operators participating in the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) offset their CO2 emissions above a baseline level Regulators and Governments: They set the rules and regulations for compliance markets, ensuring that industries adhere to emission caps. Governments or international bodies, such as the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), run and regulate these markets. Brokers: These entities facilitate the buying and selling of carbon credits. They provide platforms for trading and ensure transparency and efficiency in the market. Investors and Financial Institutions: They provide the necessary capital for developing carbon reduction projects. Hedge funds, banks, and other financial institutions are increasingly active in the carbon market. Marketplaces: Platforms where buyers and sellers can trade carbon credits. Examples include the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) and the Gold Standard. Startups & Research Institutions: These are entities that create innovations in the system for monitoring, tracking, verification and modelling GHG emissions, as well as support marketplace exchanges. MAJOR CHALLENGES IN ESTABLISHING AND OPERATIONALIZING CARBON MARKETS Amidst all the hype, it is important to note that realizing carbon credits within the global carbon market systems is fraught with challenges. Nevertheless, these issues present unique opportunities for advancement through participation, collaboration and commercialization for a wide range of stakeholders. For example, the need for regulatory frameworks and operational manuals to guide the federal, state and local governments in light of the limited technical expertise highlights a huge prospect for consulting opportunities. Furthermore, the issue of integrity and credibility of green projects where additionality, double counting, permanence and leakages are critical to meeting global standards in carbon emissions tracking, underscore the need for research and innovation. Reliable measurement, reporting and verification systems (MRV) support

Climate Finance and Emerging Issues from COP 29: What Next for Nigeria?

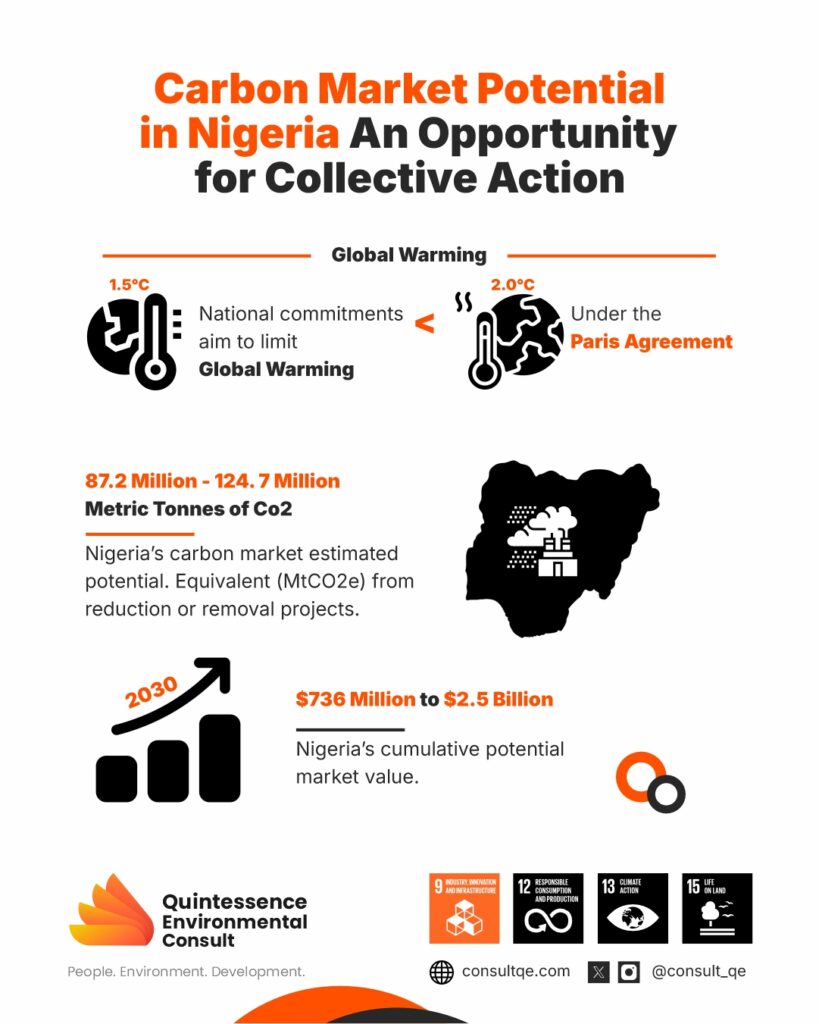

KEY TAKEAWAYS: COP29 set new, ambitious financial goals, including tripling the annual climate finance commitment for developing countries to $300 billion and aiming to mobilize $1.3 trillion annually by 2035. The Loss and Damage Fund, established during COP27, was further operationalized at COP29. This fund aims to assist vulnerable countries in dealing with climate-related disasters. COP29 made progress in refining international carbon market rules to enhance environmental integrity and prevent double-counting, which is vital for global carbon trading and emission reductions. Nigeria has made strides in climate finance through the 2021 Climate Change Act and initiatives such as the $50 million Carbon Vista fund. The country launched a carbon market initiative targeting a $2.5 billion market and continues to focus on renewable energy, transportation, agriculture, and forest conservation under its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Key challenges for Nigeria include strengthening the Climate Change Act, mobilizing public funds for the Climate Change Fund, enhancing regulatory frameworks for carbon markets, and raising public awareness of climate finance benefits. Establishing a centralized carbon registry and improving collaboration between federal and sub-national governments are crucial next steps. WHAT IS CLIMATE FINANCE? According to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), climate finance refers to local, national, or transnational financing—drawn from public, private, and alternative sources of financing—that seeks to support mitigation and adaptation actions that will address climate change. Climate finance provides a framework for setting up and dispensing financial resources and instruments to foster climate action, particularly to support investments required to transition to a low-carbon economy, especially for developing countries. It should be noted that climate financing instruments can be in the form of grants and donations, green bonds, equities, debt swaps, guarantees, and concessional loans, which can be employed for different activities including mitigation, adaptation, and resilience building. It is noteworthy to highlight carbon emissions trading, which is a crucial component of the carbon finance mechanism. Emissions trading is an innovative market-based system that allows entities to trade in carbon credits, which aims to encourage the reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions globally. Its operational framework can vary from region to region or even state to state, based on local regulations and policies. Overall, it is a versatile mechanism that derives funding for climate action, especially in developing economies. It is important to mention that Nigeria’s Climate Change Act, established in 2021, birthed the Nigeria Climate Change Council (NCCC), which leads climate change policy and action in Nigeria. The Nigeria Climate Change Act also established a climate change fund that will derive funding from multilateral sources, including climate finance instruments as defined above. Accordingly, it is reasonable to ask, how far has the NCCC fared since 2021, and what progress has been made in establishing the climate change fund? HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT AND INTERNATIONAL REGULATORY FRAMEWORK FOR CLIMATE FINANCE The historical development of climate finance can be traced back to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992. This landmark agreement established the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities,” recognizing that developed countries, with their historical emissions, should take the lead in addressing climate change. This included providing financial and technological support to developing countries. In 1997, the outcome of the Kyoto Protocol further elaborated on the commitment of developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and provide financial resources to developing countries. It established the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), allowing developed countries to invest in emission reduction projects in developing countries. However, it was not until 2015 that significant progress was made through the Paris Agreement. The Paris Agreement marked a significant turning point, with all countries committing to reduce their emissions and strengthen climate resilience. It also reaffirmed the commitment of developed countries to mobilize $100 billion per year by 2020 to support climate action in developing countries. CLIMATE FINANCE POST-PARIS AGREEMENT Since then, efforts have focused on scaling up climate finance, diversifying funding sources, and improving the effectiveness of climate finance flows. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s seventh assessment of progress towards the UNFCCC goal finds that in 2022, developed countries provided and mobilized a total of USD 115.9 billion in climate finance for developing countries, exceeding the annual USD 100 billion goal for the first time. This achievement occurred two years later than the original 2020 target year, but one year earlier than projections produced by the OECD prior to COP26. Some multilateral funds that developing countries can access include the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the Global Environment Facility (GEF), and the Adaptation Fund (AF). These funds were established over the years as financial instruments of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to provide resources to developing countries. The UNFCCC maintains a finance data portal, which is very helpful in presenting data and information about financial flows and projects in developing countries. There are several other funding sources and types, including private sector engagements, due to the increasing role of private finance in sustainable investments, which are facilitated by green bonds, impact investing, and climate-related financial disclosures. The World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) has made significant progress in this domain, elucidating the operational frameworks that support access and sustainable practices that guarantee returns on investments. It is pertinent to note that the value of the global carbon market reached a record high of $949 billion in 2023, a 2% increase from the previous year. The global carbon offset/carbon credit market is expected to grow from $331.8 billion in 2022 to $1.6 trillion by 2028. COP 29 AND EMERGING ISSUES ON CLIMATE FINANCE The 29th Conference of the Parties (COP29) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was held in Baku, Azerbaijan, from the 11th to the 22nd of November 2024. Analysts from around the world dubbed COP29 the “finance COP” due to high expectations surrounding the subject, as well as the global demand to break through limiting barriers to ambitious action by stakeholders. The UN Climate Change Conferences (COPs) take place

Unregulated Drilling of Water Wells in Nigeria: Risks, Regulatory Challenges and Strategic Way Forward.

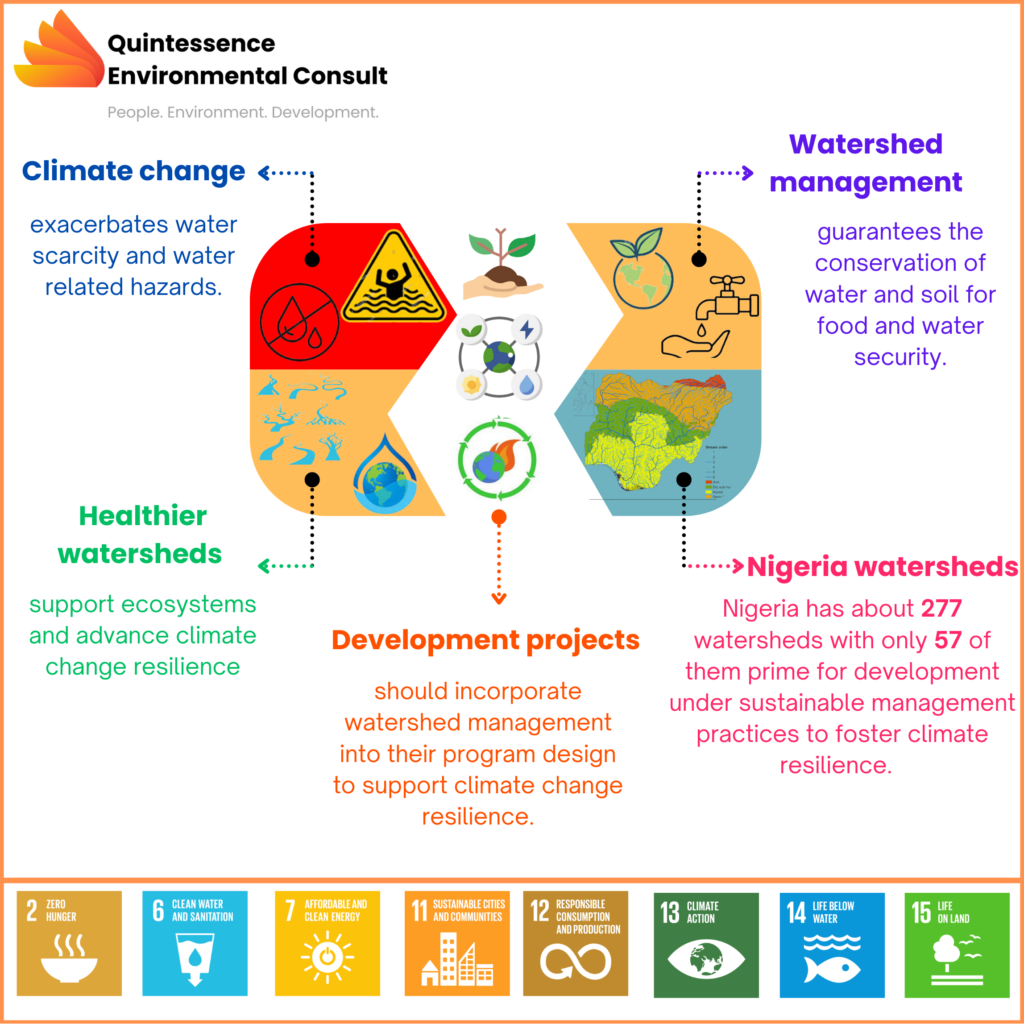

The Linkages Between Climate Change and Watershed Development in Nigeria

Key Takeaways Climate change exacerbates water scarcity and water related hazards. Watershed management guarantees water and soil conservation for food and water security. Healthier watersheds support ecosystems and advance climate change resilience Development projects should incorporate watershed management into their program design to support climate change resilience. Nigeria has about 277 watersheds with only 57 of them prime for development under sustainable management practices to foster climate resilience. INTRODUCTION In 2012, Nigeria suffered an estimated loss of $16.9b in damaged properties, oil production, agriculture and others due to flood events. Since then, large flooding events have become recurrent every year. The damages caused by these challenges are directly associated with poor watershed management and increasing climate change impacts in Nigeria (1,2). The last major flood in Nigeria which happened in Borno State exemplifies the phenomenon. But what exactly are watersheds? Watersheds are the most valuable land units in any given location where water, soil and other associated resources are found in abundance for productive human use. A watershed is defined as the area where a river catches its water. The incoming waters that form the streams and river networks in the area come from precipitation, runoff, and rivers upstream. The flowing river provides a source of fresh drinking water and nutrients for soils, supporting life in and around the area. However, urbanization, climate change and poor landuse can diminish the capacity and potential of watersheds to support life. SIGNIFICANCE OF WATERSHEDS Sustainable human development requires access to water for domestic, agricultural and industrial purposes. Similarly, growing food requires good soil with the right balance of nutrients. This establishes the linkages between watershed health and human development. Watersheds are affected by climate change which can reduce the quantity, quality, timing and distribution of water. The cumulative impacts of past land-uses, water withdrawals, and disturbances in a watershed are all exacerbated by climate change (3). Effective watershed management is essential for several reasons: Water Supply: Watersheds are the source of our drinking water, irrigation for agriculture, and water for industrial use. Flood Control: Proper management can help mitigate floods by reducing runoff and soil erosion. Water Quality: Protecting watersheds helps maintain water quality by preventing pollution and sedimentation. Biodiversity Conservation: Healthy watersheds support diverse ecosystems, including plants, animals, and microorganisms. Economic Development: Sustainable watershed management can contribute to economic growth by supporting agriculture, tourism, and other industries. Climate Resilience: Mitigating the adverse effects of extreme climatic conditions, such as drought and desertification, on crops, humans, and livestock. SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS FOR WATER AND FOOD SECURITY IN NIGERIA In Nigeria, the Federal Government in collaboration with development partners such as the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), Africa Development Bank (AfDB) and World Bank has ramped up investments in developing agriculture and water resources. For example, the World Bank is supporting the development of dams for irrigation and power generation through the Sustainable Power and Irrigation in Nigeria (SPIN). Similarly, the Special Agro-Industrial Processing Zone (SAPZ) program, as well as the Value Chain Development Program (VCDP) were launched by the AFDB and IFAD respectively. While these programs are significant and undergo extensive environmental and social screening before approval, integrated watershed management is not well-aligned with their development objectives. Pranay Panjala and his co-workers from the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) evaluated Nigeria’s watersheds and determined that there were up to 277 watersheds across the country. The researchers used a multi-criteria dataset of biophysical parameters including temperature, precipitation, slope, soil depth, soil texture, and length of growing period to establish that only 57 out of the 277 watersheds in Nigeria were suitable and prime for economic development. Their result also implies that the remaining 220 (covering more than 70% of the country) had some type of limitation across the biophysical parameters which does not guarantee economic value without innovative and sustainable measures. Accordingly, poor management of watersheds in Nigeria will increase human vulnerability to hunger, disasters and other environmental challenges. KEY PRINCIPLES OF WATERSHED MANAGEMENT Modern watershed management practice requires an integrated approach providing a holistic consideration for the interconnectedness of various factors, including land use, water resources, and ecological processes. Also, engagement and participation is comprehensive. Involving local communities in decision-making processes ensures ownership and sustainability of management practices. Other key principles of watershed management include: Sustainable Land Use: Promoting sustainable land use practices, such as agroforestry, conservation agriculture, and reforestation, helps protect soil and water resources. Water Conservation: Implementing water conservation measures, like efficient irrigation techniques and rainwater harvesting, helps reduce water consumption. Pollution Control: Controlling pollution from point and non-point sources is crucial for maintaining water quality. Monitoring and Evaluation: Regular monitoring and evaluation of watershed health and management practices are essential for adaptive management. THE CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES Nigeria’s agricultural and water resources sectors present a wealth of development opportunities, driven by the country’s vast land, favorable climate, and growing population. However, there is growing concern about the impacts of climate change, casting a shadow of challenges. Increased population and urbanization as well as loss of forest cover and land degradation are increasing surface temperatures, soil erosion and water scarcity. Despite these challenges, there are opportunities to improve watershed management: Technological Advancements: New technologies, such as remote sensing and GIS, can enhance monitoring and decision-making. Policy and Institutional Reforms: Strong policies and effective institutions are essential for implementing sustainable watershed management practices. Public Awareness and Education: Raising public awareness about the importance of watersheds and promoting environmental stewardship can drive behavioural change. CONCLUSION Climate change is now intricately linked to watershed development, influencing hydrological processes, water availability, and ecological balance. As the climate warms, precipitation patterns become increasingly erratic, leading to more frequent and intense rainfall events and prolonged droughts. These shifts disrupt the delicate equilibrium of watersheds, affecting water flow, sediment transport, and nutrient cycling. In response to these challenges, sustainable development programs must now adapt their climate change plans to include integrated watershed management. This involves implementing climate-resilient strategies, such as sustainable land use practices, water conservation measures, and infrastructure upgrades, aligning with global climate goals and protecting vital ecosystems. REFERENCES Amangabra, G.T. & Obenade,