Why The Global Plastics Treaty Failed and What it Means for Nigeria

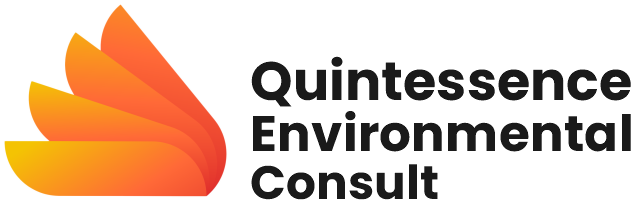

Each year, the world produces over 400 million tonnes of new plastic. In the absence of significant policy reforms, this figure is projected to increase by nearly 70% by 2040, according to a 2024 OECD policy scenario report8. The proposed Global Plastic Treaty aims to address plastic pollution across its entire lifecycle, covering production, consumption, waste management, and disposal. In addition, the treaty is expected to provide funding and technology transfer to support plastic waste management.

Formal negotiations on the treaty were led by the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC), which commenced in December 2022, with representatives from 175 countries participating. In addition, major financial institutions were expected to play a key role in promoting the development and implementation of the treaty within the global financial sector5. However, following the final round of talks (INC-5.2)7, held in August 2025 in Geneva, Switzerland, the Committee failed to reach a unified position. The breakdown of these negotiations has left the international community without a comprehensive, legally binding framework to effectively tackle the escalating plastic pollution crisis. A major impediment to progress was the INC’s reliance on consensus-based decision-making—a diplomatic mechanism that enables individual delegations to delay or obstruct collective outcomes. Attempts to reform this approach, including proposals for qualified majority voting in specific contexts, proved politically contentious and ultimately unsuccessful. Consequently, a small number of dissenting states were able to stall the entire negotiation process. This paper explores the main factors contributing to the negotiation deadlock and assesses the broader implications for Nigeria, one of Africa’s largest producers of plastic waste.

Environmental Impact Of Plastic Additives In Nigeria: An Emerging And Overlooked Contaminant Of Concern

Plastic products often contain additives such as plasticizers, stabilizers, flame retardants, pigments, PFAS-based coatings, and biocides, which are incorporated into polymer matrices to enhance their performance. Since most of these additives are not chemically bonded to the polymers, they can leach out, evaporate, or be released along with micro- and nanoplastics into the environment.

While global concern about this chemical aspect of plastic pollution is increasing, in Nigeria—where plastic waste management faces challenges like high waste production, limited formal recycling, open dumping, and frequent flooding—these additives remain a largely overlooked but potentially significant source of environmental contamination (Ebere et al., 2019; Faleti, 2022).

Waste Sorting: The Holy Grail of Plastic Recycling

Plastic waste has become an undeniable global crisis, presenting severe environmental and socio-economic challenges. Our modern lives are intricately woven with plastic, making it seemingly impossible to extricate ourselves from its pervasive presence. The production of virgin plastic continues to soar, with estimates suggesting a cumulative volume exceeding 25,000 million metric tons by 2050 if the current 8.4% growth rate persists.

Alarmingly, of all virgin plastic ever produced, only a minuscule 9% is recycled, while 12% is incinerated. The vast majority, a staggering 79%, accumulates in landfills or pollutes our natural environment3. While recycling is theoretically the most preferred method for plastic waste management, allowing for infinite reprocessing, this remains a distant ideal. Currently, only about 10% of all recycled plastic enters a second recycling cycle3. This stark reality implies a continuous influx of virgin plastic into the market, even with increased recycling efforts. The problem is exacerbated by the prevalence of single-use plastics, which are often discarded within a month or less, contributing significantly to environmental accumulation.

Understanding Plastic Credit as a Market-Based Scheme Incentive for Plastic Waste Management

KEY TAKEAWAYS Plastic credits transform waste management into a profitable venture by rewarding organizations that collect or recycle plastic waste and enabling producers to offset their footprints through credit purchases. Multiple globally recognized bodies (e.g., Verra’s Plastic Credit Standard, Plastic Bank, PCX, GPP) employ differing verification criteria, leading to a lack of a universally accepted standard. Implementing plastic credit in Nigeria will bridge the financing gap and encourage plastic collection systems that were otherwise not economical. Transparency, universally accepted standards, and rigorous verification by third-party organisations are essential for the success of the plastic credit system and the reduction of greenwashing. INTRODUCTION According to the world-bank, it is estimated that USD 1.64 trillion of investment will be required by 2040 to tackle pollution[1]. To meet this financial requirement, waste management must be made profitable. Plastic credit is an auditable, tradable, transferable certificate that represents a unit of plastic reduction. The credits are typically earned by organizations that collect and recycle plastic waste, and are bought by organizations that produce or consume plastic to offset their plastic footprint. The revenue made by selling the credit is then used to support plastic waste management programs, resulting in further credit generation. This way, the plastic credit incentivizes waste management by ‘penalizing’ plastic production and consumption while ‘rewarding’ plastic waste prevention. Plastic waste management is a capital-intensive program. In many developing countries, the cost of solid waste management can be as 50% of the total municipal budget [2]. Therefore, there is a need to incentivize plastic waste management by making it sustainable and scalable. The plastic credit system is one innovative way of injecting funds into the waste management program in a sustainable manner. Overall, this acts as an extended producer responsibility (EPR)scheme that will make plastic waste management economically viable and scalable. HOW TO EARN AND TRADE PLASTIC CREDIT All programs and investments that lead to a reduction in plastic pollution typically earn plastic credit after verification and certification by a third-party organization. These include upstream measures aimed at preventing and reducing plastic waste generation and downstream measures such as waste collection and recycling. The credits are issued for specific quantities of plastic waste removed or prevented from entering the environment above a recognized baseline. The baseline refers to the original waste prevention, collection or recycling capability of an organization. This scheme leads to additionality, i.e a net and incremental reduction in plastic waste pollution. Typically, one credit unit equals one metric tonne of plastic waste managed (collected/recycled) beyond that baseline. According to world bank estimate, the value of the unit is 140- 670 USD, depending on the waste collection context and issuing organization[1]. Companies, governments, and individuals who produce or consume plastic can purchase these credits as a way to offset their plastic footprints. CREDIT CERTIFICATION Plastic credit is issued only for plastic collected or recycled above the baseline effort. To ensure transparency, waste reduction efforts must be independently verified by third-party organizations that would then issue a credit certificate. Some of these certification bodies enjoy global recognition, such as: The Plastic Bank, Verra’s Plastic Credit Standard, The Global Plastics Platform (GPP), BVRio, Plastic Credit Exchange (PCX), Zero Plastic Oceans (ZPO), etc [1,3]. These organizations employ different standards for verification and issuance of certificates. This is one of the major issues with the plastic credit since there is no uniformly accepted standard, and credit issued by one organization may not be recognized by a company that has not subscribed to that organization. IMPLEMENTING PLASTIC CREDIT SCHEME IN NIGERIA Plastic crediting can be used as a compliance mechanism within EPR schemes. Producers can purchase plastic credits to meet some of their obligations. If operationalized in Nigeria in a transparent, performance driven and structured manner, plastic credit can bridge the financing gap and encourage collection systems that were otherwise not economical. Setting up a plastic crediting system in Nigeria will involve several key steps, including understanding the regulatory environment, engaging stakeholders, creating a transparent tracking mechanism, and developing infrastructure for collection, recycling, and credit distribution. CHALLENGES WITH PLASTIC CREDIT SYSTEMS Not all plastic waste reduction or recycling projects are equally effective. Some may provide minimal environmental benefits, while others may lead to long-term improvements. One of the key challenges is ensuring that credits are issued only for projects that have a substantial impact. If credits are issued too loosely, without rigorous verification of net impact, the value of plastic credits could drop, undermining the financial incentive for the scheme. Additionally, relying too heavily on plastic credits as an offset mechanism might delay the necessary reduction in plastic production and consumption by companies and encourage greenwashing [1,3]. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR A SUCCESSFUL PLASTIC CREDIT SCHEME Plastic credit should have a clear governance framework that involves external stakeholders from various sectors. The program should use relevant, consistent, universally accepted standards and definitions for measuring impact. The impact should not just pertain to the volume of plastic collected, but also to plastic types, its use, and end point. This is essential because removing one ton of plastic in one context is not the same as removing it in another. Double counting in different schemes or with existing EPR and tax systems should be avoided. The value of Credits should reflect the cost of waste management rather than the material value. This includes the cost of waste management infrastructure and living wages for waste workers. Credit sold to organizations should be transparently reported against the volumes of plastic materials put on the market by the buying companies. Such organization should demonstrate prove they have explored all available waste prevention options given their peculiar situation. These efforts should adhere to the principle of waste management hierarchy by prioritizing reuse and recycling before incineration and disposal of waste. This is essential to prevent organizations from using plastic credit for greenwashing. CONCLUSION Plastic credits are a market-based solution designed to address the global plastic waste crisis by incentivizing plastic waste management. The incentive is provided when plastic reduction efforts generate credit,

Understanding the Global Plastics Treaty

KEY TAKEAWAYS The Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) of the UNEP is developing a binding international framework for managing plastic waste. Significant progress has been made at the 5th meeting of the INC with proposals of a plastics production cap, clearing existing plastics, technology transfer and financing the provision of the proposal. Several challenges may hamper the success of the treaty when eventually ratified including conflict with business interests, political and policy priorities of member countries, and lack of power of enforcement over parties The national policy on plastic waste management proposed by Nigeria has provisions that are very much in line with those of the INC, showing that Nigeria is moving in the right direction. Sub-national governments in Nigeria may not see plastic waste as a priority issue and may require incentives to take action. INTRODUCTION Plastic waste accumulating in oceans, waterways, and landscapes has become a global challenge, causing harm to wildlife, ecosystems, and human health. The Plastic Treaty refers to a proposed Intergovernmental Legally Binding Instrument (ILBI) that seeks to tackle plastic pollution throughout its entire lifecycle, from production and consumption to waste management and disposal. The need for this treaty was raised in resolution 5/14 at the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) of the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) on March 2, 2022[1]. As of December 2022, 175 countries have joined the negotiation process on the Treaty. The treaty is to be drafted by the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee(INC), convened by the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP), taking into account the principles of the Rio Declaration but with differentiated responsibility to individual nations’ circumstances and capabilities. The fifth and supposed final session of the INC (INC-5.1) took place in Busan, South Korea, in November 2024, but it ended without an agreement. A second part of the 5th session (INC-5.2) is scheduled for August 2025 in Geneva, Switzerland[2]. The treaty, when finally agreed upon and judiciously implemented by member countries, is expected to reduce Plastic Production, Consumption and disposal, promote sustainable Waste Management practices, Recycling, and support Research and Innovation. The proposed plastic treaty includes 32 articles, some of which offer a framework for ratification, documentation, and implementation, while others address core issues of plastic waste, such as plastic production caps, existing plastic waste, and improvement of plastic design and its alternative materials. The implementation seeks to preserve the economic development of the parties, not disrupt international trade, protect local customs, and cultural heritage. The implementation of the treaty will be monitored and regulated by a conference of parties Some of these core issues are elaborated further on below. Plastic production Caps and alternatives: According to Article 3 of the proposed treaty, member countries are to end the production and consumption of certain categories of plastics listed in Annex X and Y after a yet to be agreed upon date but after 2030. These products include single-use plastics and plastics containing certain toxic compounds, including DEHP (CAS number 117-81-7), DBP (CAS number 84-74-2), BBP (CAS number 85-68-7) and IBP (CAS number 84-69-5), as well as children’s toys containing heavy metals, such as lead and chromium. Article 4 allows member countries, according to their respective socioeconomic goals, to seek to delay enforcement of the ban not later than 5 years after the stipulated dates. Articles 5 and 6 proposed research into better design and sustainable alternatives to plastic to ensure circular economy practices[3]. Waste management: Articles 7 to 9 focus on waste management, including guidance against the leakage of plastic waste into unregulated systems as well as dealing with existing plastic waste. It emphasized the primacy of the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes. Member countries are encouraged to set targets to increase the collection and recycling rates of plastic waste, identify plastic accumulation zones and engage in joint clean-up campaigns, especially for transboundary waste.[3] Technology transfer and Financing mechanism: The treaty’s success depends on robust technology transfer and adequate financing. As the developed countries have generally contributed disproportionately to the plastic problem, they equally bear a disproportionate burden of the financial commitment. Developed parties are expected to fund the treaty through primary plastic polymer fees, extended producer responsibility schemes, development strategies, bilateral & multilateral funding, private sector investment, voluntary contributions, and national budgets. The fund (Global Environment Facility Trust Fund) will be managed by the conference of parties. Priority of access is given to the most vulnerable countries, such as least developed countries (LDCs), landlocked nations, small island developing states (SIDS), lower riparian countries and archipelagic states[3]. POTENTIAL THREAT TO THE GLOBAL IMPLEMENTATION OF THE TREATY Conflict with business interests: Business interests may clash with the implementation of the treaty, as many industries depend on plastic products for packaging, manufacturing, and consumer goods. The economic interests of these industries could directly conflict with the treaty’s regulations, especially Article 3, which calls for a ban on the production and consumption of specific types of plastics. Diverse government Priorities: Government priorities can shift due to local politics, preventing parties from meeting their commitments. A clear example of this is the current U.S. president, Donald Trump. Since taking office, he has withdrawn from several multilateral agreements[4], including the climate change agreement, and has expressed his opposition to the plastic treaty. He also reversed the ban on plastic straws in place before his presidency [5]. Such actions from the president pose a significant threat to the success of the treaty. Moreover, countries experience varying levels of plastic pollution, making it difficult to create a global treaty that is fair and equitable for both developed and developing nations. This fear exists despite the financial obligations the treaty imposes on developed countries. This disparity partly contributed to the inability of members to reach an agreement during the recent INC meeting in Busan, South Korea. Implementation and Enforcement: The proposed treaty provides guidelines to help countries adhere to its provisions, but there are no mechanisms in place to force sovereign nations to comply if they fail to do so. Additionally,