KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Plastic additives are chemical substances commonly incorporated into plastic products to improve their specific functions and performance. These include plasticizers, stabilizers, flame retardants, pigments, and PFAS-based coatings.

- Additives can enter the environment through various pathways, such as leaching from intact plastic materials, the breakdown of plastics into microplastics, or direct discharges from industrial facilities and landfill leachates.

- Once in the environment, these additives can lead to significant ecological impacts, including disruptions in species composition and alterations in sex ratios among aquatic organisms. In Nigeria, such additives have been detected in multiple aquatic environments, including rivers, lagoons, and sediments.

- To mitigate the release and impact of plastic additives in Nigeria, it is essential for the government to implement a standardized national monitoring program, conduct integrated ecotoxicological assessments, and promote green and safer product alternatives through regulatory and policy measures.

INTRODUCTION

Plastic products often contain additives such as plasticizers, stabilizers, flame retardants, pigments, PFAS-based coatings, and biocides, which are incorporated into polymer matrices to enhance their performance. Since most of these additives are not chemically bonded to the polymers, they can leach out, evaporate, or be released along with micro- and nanoplastics into the environment. While global concern about this chemical aspect of plastic pollution is increasing, in Nigeria—where plastic waste management faces challenges like high waste production, limited formal recycling, open dumping, and frequent flooding—these additives remain a largely overlooked but potentially significant source of environmental contamination (Ebere et al., 2019; Faleti, 2022).

PATHWAYS OF RELEASE INTO THE ENVIRONMENT

Additives are introduced into the environment through four primary pathways:

- Leaching from intact plastic items such as PVC pipes and food packaging,

- Release triggered by the weathering and breakdown of plastics into microplastics,

- Direct discharge from industrial or municipal sources, including plastic manufacturing and landfill leachates, and

- Atmospheric deposition of volatile additives and airborne particles.

In Nigeria, the widespread use of single-use plastics, poor source segregation, informal recycling systems, and common practices like open dumping significantly increase the likelihood of additive release into soil and water bodies. Research on Nigeria’s coastal and river systems has detected microplastics and polymers—such as PVC, PE, PP, and PET—known to carry additives, along with organic pollutants found in both sediments and aquatic organisms (Abiodun et al., cited in Faleti, 2022; Ebere et al., 2019).

The hydrological dynamics of key Nigerian water bodies—including the Niger Delta estuaries, Cross River, and Lagos Lagoon—support the rapid movement and deposition of these pollutants. Hydrophobic additives, such as brominated flame retardants, tend to bind to suspended particles and settle in sediments, while more polar substances, including PFAS, remain dissolved in water, enabling their wide dispersal (Adewuyi, 2024; Aborode et al., 2024).

- Phthalates (phthalic acid esters): A notable regional study by Orok et al. (2014) measured phthalates and similar additives in surface sediments from the Cross River, Nigeria. The results shows detection of di (ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), di (n-butyl) phthalate (DnBP) and di (isobutyl) phthalate (DiBP at concentrations of 86.76, 17.41 and 29.64 mg/kg respectively. The study concluded that phthalates were widespread in sediments affected by urban and petrochemical activities highlighting Niger Delta as a pollution hotspot.

- Bisphenol A (BPA) and related compounds: Bisphenol-A (BPA) belongs to category 1 of Endocrine Disruptive Chemicals (EDCs) that is acutely toxic to living organisms. A detailed study conducted by Adeyi et al. (2019) detected BPA in commonly consumed foods in the southwestern region, including vegetable oil (28.4 ng/g), canned fish (26.3 ng/g), canned beef (21.3 ng/g) and crayfish (17.5 ng/g). Although these concentrations were below the 600 ng/g limit of the European Commission for BPA in foods, they represent an emerging issue of public health concern. Other studies found BPA and related endocrine-disrupting compounds in pointing to both environmental and food-chain exposure routes.

- PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances): Although national data on PFAS remain limited, emerging show that substances such as PFOS, PFOA, and their congeners are detectable in some water and sediment samples. include industrial discharges, textile and food-packaging industries, and imported consumer products treated with PFAS-based chemicals.

- Microplastics as carriers of additives: Extensive studies on marine debris and microplastic pollution in Nigeria—especially in areas like Lagos Lagoon and Elechi Creek—have found high concentrations of microplastics. Some microplastic particles were contaminated with organic pollutants such as PAHs and PCBs, suggesting simultaneous release of embedded additives

- Other additive-related compounds: Targeted research in Lagos rivers has identified low concentrations of nonylphenol, octylphenol, and other endocrine-disrupting compounds, indicating the presence of alkylphenol additives or their degradation byproducts. While heavy metal-based pigments and stabilizers have mainly been studied within broader assessments of metal pollution, their link to plastics—such as from paint flakes or waste plastics—is recognized.

Together, these findings indicate that Nigeria is indeed affected by additive pollution, with hotspots near urban centers, estuaries, and areas with industrial or petrochemical activity. However, a comprehensive and systematic national monitoring framework for plastic additives across environmental media is still lacking.

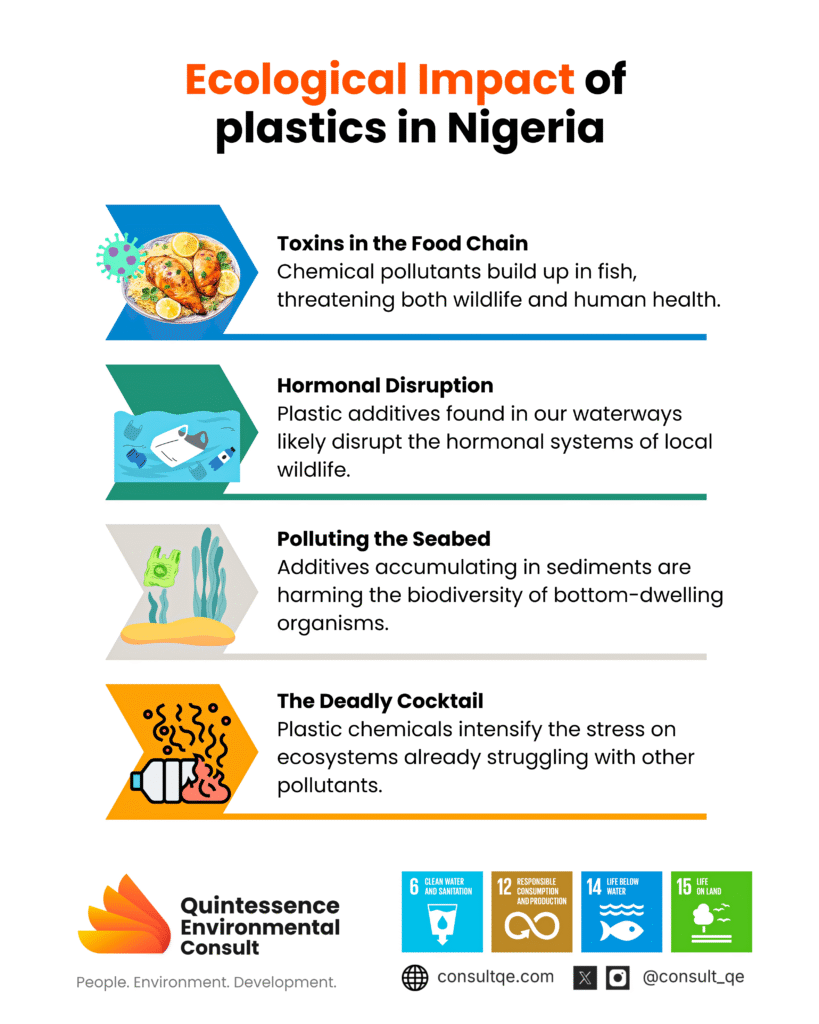

ECOLOGICAL EFFECTS

- Bioaccumulation and Trophic Transfer: The detection of BPA and other endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) in fish tissues, such as in studies involving catfish, suggests that these contaminants are absorbed by edible species. This raises concerns not only for aquatic predators but also for humans who consume these fish. In estuarine environments with known contamination, fish and bottom-dwelling invertebrates may serve as pathways for the movement of additives up the food chain.

- Endocrine and Reproductive Effects: International research has linked phthalates and bisphenols to hormonal disruptions in aquatic organisms, including altered sex ratios and the induction of vitellogenin in fish and amphibians. Given that these substances have been detected in Nigerian water bodies and organisms, similar sublethal effects are likely to occur in local wildlife—especially in estuarine areas like the Cross River and Niger Delta, where phthalates have been found in sediments.

- Impacts on Sediments and Benthic Communities: Sediments in regions like the Niger Delta and Cross River, which accumulate hydrophobic additives, also support diverse benthic life. Contaminated sediments may disrupt these communities by altering species composition, reducing biodiversity, and impairing critical ecosystem functions such as organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling—processes vital to the health of Nigerian mangroves and estuarine fisheries.

- Compounded Stress from Multiple Pollutants: Aquatic ecosystems in Nigeria are already under pressure from pollutants such as hydrocarbons, heavy metals, and nutrient overloads. The presence of plastic additives—some of which act as endocrine disruptors or immunotoxins—can intensify these existing stresses, leading to greater ecological damage. For example, additives like PFAS or flame retardants in sediment may further weaken immune or reproductive functions in fish populations already coping with other contaminants.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND PRIORITIES FOR NIGERIA

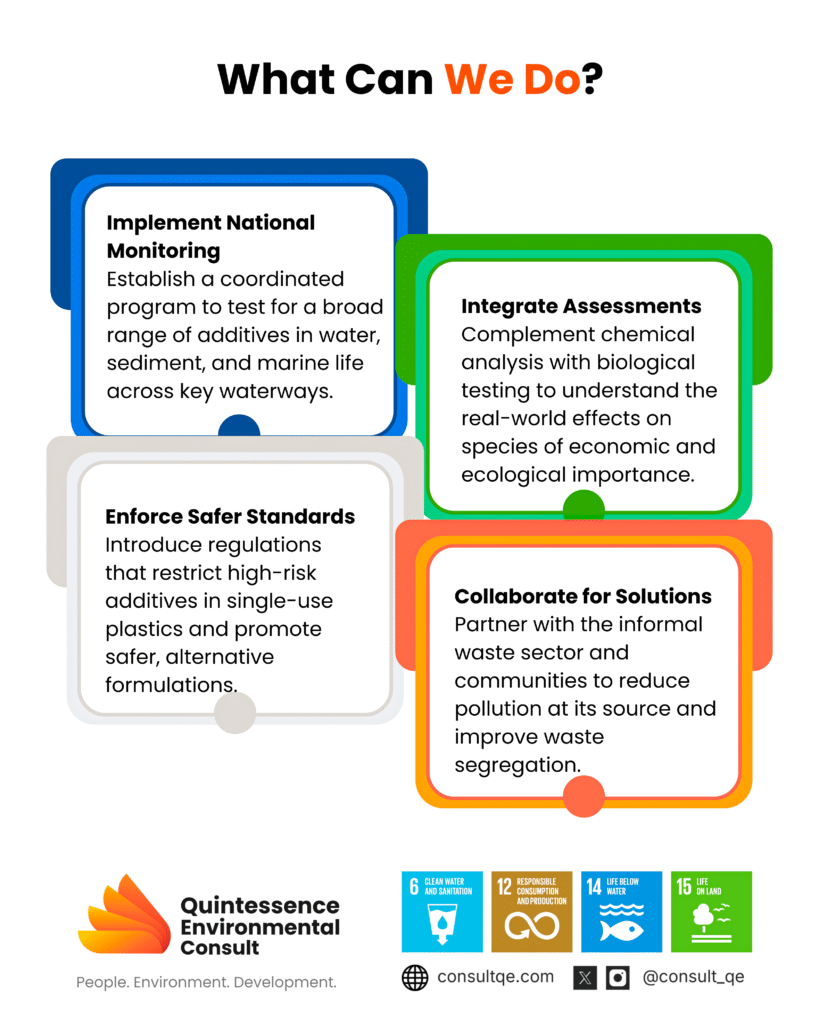

- National Standardized Monitoring Program: Establish a coordinated, country-wide monitoring initiative focusing on key aquatic systems such as the Lagos Lagoon, Cross River, Niger Delta estuaries, and Ogun River. This should involve multi-media sampling across water, sediment, and biota, using consistent protocols to test for a broad range of additives, including phthalates, bisphenols, PBDEs/HBCD, organophosphate flame retardants, PFAS, and heavy metal-based stabilizers. To address limitations in local capacity, Nigeria should collaborate with regional laboratories and international partners.

- Integrated Ecotoxicological Assessment: Complement chemical monitoring with biological assessments, such as biomarker testing (e.g., vitellogenin levels, cytochrome P450 activity), reproductive health evaluations, and ecological surveys of affected estuarine communities. Prioritize species of local ecological and economic importance, including Clarias spp., tilapia, benthic invertebrates, and mangrove crabs, to ensure relevance to Nigerian ecosystems.

- Green Procurement and Safer Product Standards: Introduce regulations that restrict the use of high-risk additives in single-use plastics such as high-migration phthalates and unvetted BPA alternatives and promote industry adoption of safer additive formulations. Strengthen extended producer responsibility (EPR) systems to reduce the environmental release of additive-laden plastic products.

CONCLUSION

Additives elevate plastic pollution from a mere physical issue to a complex chemical hazard. Research in Nigeria has confirmed the presence of phthalates, bisphenols, and microplastics contaminated with chemical residues in both coastal and inland waters. At the same time, preliminary findings on PFAS reveal significant data gaps. Although there is limited direct evidence of population-level ecological effects within Nigeria, global data on the toxicity of these additives, alongside local findings of high microplastic concentrations and additive contamination, point to a clear ecological risk, particularly in sensitive estuarine and mangrove habitats that support fisheries and local livelihoods. Tackling this issue in Nigeria will require expanded environmental monitoring, ecotoxicological studies that integrate chemical and biological data, precautionary regulations, and active collaboration with the informal waste sector to curb additive pollution at its source.

REFERENCES

- Aborode, A.T., et al. (2024). PFAS Research in Nigeria: Where Are We? Review (PMC) — highlights current PFAS data gaps and initial measures.

- Adeyi, A.A., et al. (2019). Bisphenol-A (BPA) in foods commonly consumed in Southwest Nigeria. [PMC article].

- Ebere, E.C., et al. (2019). Macrodebris and microplastics pollution in Nigeria. Marine Pollution Bulletin.

- Falconer / Faleti, A.I. (2022). Microplastics in the Nigerian environment — a review. ChemRxiv / preprint.

- Occurrence of Bisphenol A in ponds, rivers and lagoons in South-Western Nigeria and uptake in catfish (2021). research report/article (catfish uptake study).

- Orok, E.O., Ekpo, B.O., Inyang, O.O., & Offem, J.O. (2014). Phthalates and other plastic additives in surface sediments of the Cross River system, S.E. Niger Delta, Nigeria: Environmental implication. Environment and Pollution, 3(1): 60–72.