KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Mine closure is essential for true sustainability, abandonment causes environmental, health, and social risks, as seen in Jos Plateau.

- Plan early: Closure must start at the feasibility stage with land restoration, waste, and water management.

- Engage stakeholders: Communities and civil society must play a role in shaping post-mining land use.

- Rehabilitate progressively: Restore mined-out areas in phases to cut costs and aid ecological recovery.

- Innovate land use: Repurpose closed mines for renewable energy, tourism, aquaculture, or farming.

- Nigeria must act: Enforce policies, build expertise, and strengthen community participation.

INTRODUCTION

When conversations on sustainable mining arise, they often focus on responsible extraction, environmental safeguards, and community relations during active operations. Rarely, however, do they touch the crucial, final chapter of mining: “mine closure and land rehabilitation”, a chapter that determines whether the land will become a legacy of prosperity or a scar of neglect.

WHY IT MATTERS

For decades, mining in Nigeria and indeed in much of Africa, such as the Republic of Congo, South Africa, Ghana, etc, has been driven by the excitement of discovery and profit. Unfortunately, once minerals are depleted, many companies pack up, leaving behind degraded landscapes, toxic tailings, and polluted water bodies. Communities are left to deal with the aftermath: infertile soils, unsafe pits, and lost livelihoods. The abandoned tin mines in Jos, Plateau remain a stark reminder of the dangers of ignoring post-mining land use; many have turned into deadly water ponds or barren wastelands, posing environmental and public health risks [1].

In contrast, modern sustainable mining emphasizes not only “how we mine” but “what we leave behind”. Mine closure and land rehabilitation ensure that post-mining landscapes are safe, ecologically functional, and, where possible, economically useful.

IMPACTS OF AN ABANDONED MINE

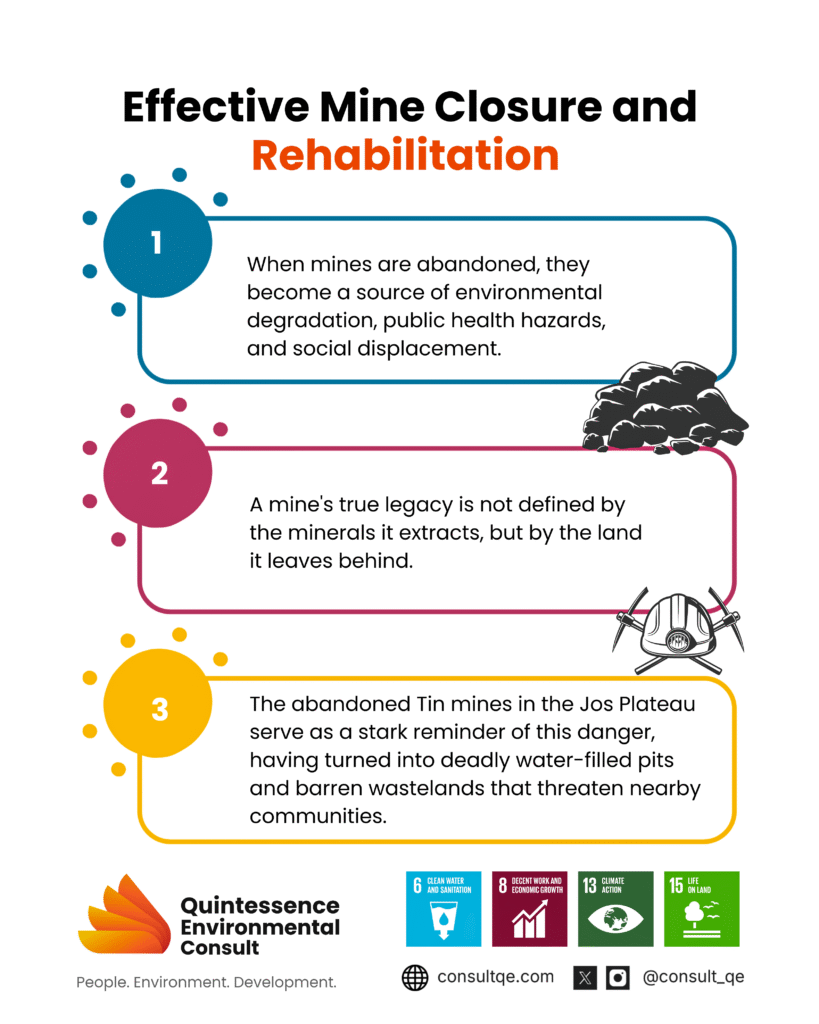

Abandoned mines leave behind more than empty pits; they create lasting scars that affect people, the environment, and local economies:

- Environmental Degradation: Exposed soils trigger erosion and gully formation, while uncovered tailings release toxic heavy metals into rivers and groundwater. Acid mine drainage further pollutes wetlands and farmland.

- Public Health Hazards: Water-filled pits become breeding grounds for mosquitoes, increasing malaria prevalence. Communities also face risks of drowning, chemical poisoning, and unsafe drinking water.

- Loss of Livelihoods: Once-fertile farmland is rendered infertile, grazing lands are lost, and fishing grounds are polluted, cutting off key sources of income for rural families.

- Safety Risks: Unsecured mine shafts and open pits pose dangers to farmers, children, and livestock.

- Socioeconomic Costs: Governments and communities bear the burden of rehabilitation, diverting scarce resources from education, healthcare, and infrastructure.

- Biodiversity Decline: Habitats are destroyed, wildlife is displaced, and invasive species often colonize disturbed landscapes, leading to ecosystem imbalance.

BEST PRACTICES FOR SUSTAINABLE MINE CLOSURE

- Comprehensive Closure Plans: A well-crafted closure plan outlines in detail how the site will transition from an active operation to a stable, safe, and productive post-mining landscape. This plan should consist of Landform Restoration (ensuring final slope angles are no steeper than 3:1 H:V for geotechnical stability), Waste Management and Remediation (including the use of geosynthetic liners or clay caps to prevent contamination), Soil Stabilization and Vegetation Recovery (with a minimum of 15 cm of topsoil for re-vegetation), and Rehabilitation of Water Resources, especially if the mining has impacted rivers, wetlands, or groundwater. Methods such as lime dosing or constructing passive treatment wetlands should also be considered to neutralize acid mine drainage.

- Stakeholder Engagement: In the discourse on mine closure and land rehabilitation, one critical element often overlooked is the role of stakeholder engagement. While closure plans typically focus on technical components like backfilling, water management, and re-vegetation, they sometimes ignore the most important variable: people. Yet, mining happens in human landscapes, lands that are farmed, inhabited, and spiritually valued. When the mine shuts down, the community remains. They include host communities, local landowners, women’s associations, youth groups, civil society organizations, traditional leaders, and even employees and contractors who depend on mining for their livelihoods. Each of these groups has a unique interest in what happens to the land after mining ends, whether it will be used for farming, housing, conservation, tourism, or renewable energy projects. Genuine engagement means involving these groups early, consistently, and meaningfully.

- Progressive Rehabilitation: One of the most effective, yet underutilized strategies in sustainable mining is progressive rehabilitation, a practice that involves restoring land in phases during the life of the mine, rather than waiting until mining operations are complete. This approach not only reduces the environmental footprint of mining but also lowers the financial and logistical burden of mine closure. This phased approach offers several key advantages. First, it spreads out the cost and labor associated with land restoration, making it more manageable for mining companies. Second, it provides an early opportunity to test and refine re-vegetation techniques, ensuring better outcomes when final closure arrives. Third, it allows for early ecological recovery, giving native plant species a head start in re-establishing themselves, and helping to prevent soil erosion and sedimentation in nearby rivers and streams.

- Innovative Land Use: Forward-thinking governments and mining companies are reimagining closed mine sites as productive, sustainable assets that serve communities and ecosystems long after extraction ends. One of the most promising trends is the conversion of former mine lands into renewable energy hubs. Abandoned pits and tailings areas, often unsuitable for agriculture or settlement, can be ideal sites for solar or wind farms. These facilities require open, non-forested land and minimal subsurface disturbance conditions that many post-mining landscapes naturally provide. In regions with strong ecological or cultural tourism potential, ecotourism is another emerging land-use model. Abandoned quarries and open pits can be converted into scenic lakes, rock-climbing parks, or wildlife reserves. These sites often attract tourists, researchers, and conservation groups while creating jobs for residents. For example, Thailand’s Lampang Coal Mine was transformed into a botanical garden and learning center, which now hosts thousands of eco-tourists annually [5]. Another option is aquaculture and water storage. Mined-out pits that fill with rainwater or groundwater can be lined and managed as fish farms or irrigation reservoirs. In Ghana, mining pits have been repurposed for fish farming, known as “Solar fish farm enterprise” [6], supplying local markets and generating new livelihoods.

- Monitoring and Aftercare: Post-closure monitoring should involve a series of structured activities designed to track the physical, chemical, biological, and social performance of the reclaimed site. It includes inspecting reclaimed slopes for erosion, testing soil and water quality, observing vegetation growth, and ensuring that tailings or waste storage facilities remain intact and contained. Monitoring should be carried out quarterly during the first two years, then annually, and should include parameters such as pH, total dissolved solids (TDS), heavy metals (e.g., lead, arsenic), and suspended solids. Without this oversight, even well-executed rehabilitation efforts can fail due to unexpected weather events, subsurface instability, or chemical leakage. Importantly, monitoring must also be transparent and accountable. Data should be shared openly with local stakeholders, environmental agencies, and the general public. Interactive dashboards, community notice boards, and stakeholder review meetings can help maintain visibility and build confidence in the rehabilitation process.

BENEFITS OF REHABILITATED MINES

Rehabilitated mines demonstrate that post-mining landscapes can be transformed from hazards into opportunities. The benefits are environmental, social, and economic:

- Environmental Recovery: Restored vegetation stabilizes soil, improves water quality, and revives ecosystems, reducing erosion and habitat loss.

- Public Health Protection Properly sealed pits eliminate drowning risks and mosquito breeding sites, lowering disease outbreaks.

- Economic Opportunities: Closed mine lands can host new industries such as farming, aquaculture, tourism, and renewable energy projects, creating jobs and sustaining local economies.

- Social Stability: Communities gain safer, productive land for housing, farming, and cultural use, reducing conflicts and displacement.

- Heritage & Education: Repurposed sites, such as museums or eco-parks, preserve mining history while educating future generations.

Case Studies of Rehabilitated Mines

Australia’s Ranger Uranium Mine is a classic example. After 40 years of uranium extraction, the mining company undertook a massive closure plan involving backfilling pits, reshaping landforms, and replanting native vegetation to restore the natural ecosystem of Kakadu National Park [2]. Finland’s Outokumpu Copper Mine was transformed into a tourism and museum site after closure, offering educational and economic opportunities for locals while preserving mining heritage [3]. South Africa’s Mpumalanga Coal Mines have also initiated programs where abandoned mines are converted into farmlands or water reservoirs to support local communities [4]. These projects employ while restoring the environmental balance.

CHALLENGES FACING MINE CLOSURE IN NIGERIA

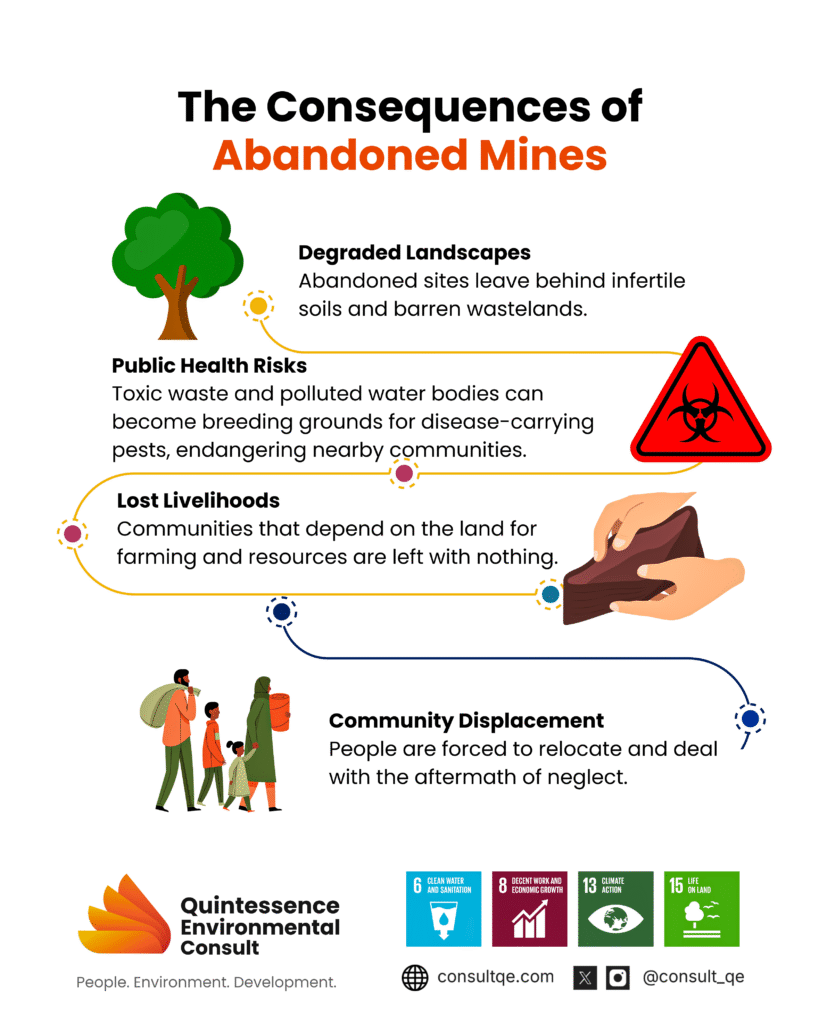

- Weak Enforcement of Closure Regulations: Although Nigeria’s Mineral and Mining Act (2007) and the EIA Act require operators to prepare closure and rehabilitation plans, enforcement is inconsistent. Many small- to medium-scale mines operate without formal closure obligations. For instance, the numerous abandoned tin and columbite pits show how weak regulatory oversight has left behind hazardous water-filled pits that now endanger communities and livestock. Without stricter enforcement, mine closure remains an afterthought rather than a legal obligation.

- Limited Financial Provisions by Operators: Many mining operators in Nigeria fail to set aside sufficient funds (such as reclamation bonds) for closure. This often results in abandoned sites once minerals are exhausted, with no resources available for rehabilitation. The financial burden then falls on local communities or government agencies, which are already underfunded. In some cases, open pits turn into breeding grounds for mosquitoes, increasing malaria risks in surrounding areas.

- Lack of Technical Expertise in Land Rehabilitation: Effective mine rehabilitation requires knowledge of soil stabilization, vegetation recovery, and water management, skills that are often lacking in Nigeria’s mining workforce. As a result, even when companies attempt rehabilitation, efforts are sometimes poorly executed, leading to erosion, invasive species, or unstable landforms.

- Poor Community Involvement in Closure Plans: Closure decisions are often made without consulting local stakeholders. This leads to land-use outcomes that fail to meet community needs. For instance, a rehabilitated site might be unsuitable for farming, the main livelihood in the area, leaving residents worse off after closure. Excluding communities from planning also fuels mistrust and conflict, making sustainable closure less likely.

THE WAY FORWARD

To make mine closure an active part of Nigeria’s mining sustainability strategy:

- The Mining Cadastral Office (MCO) should mandate detailed closure plans and bonds before granting licenses. This ensures that closure is not an afterthought but a legal and financial obligation. Requiring bonds also guarantees that funds are available for rehabilitation, even if the operator abandons the site.

- Mining companies must see closure as part of their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) obligations.

- Research institutions should develop and share low-cost rehabilitation techniques suited to Nigeria’s ecological zones. Many advanced closure technologies are expensive and not locally adaptable. Developing cost-effective, Nigeria-specific solutions will make rehabilitation more practical for operators and accessible to artisanal and small-scale miners.

- Communities must be educated on their rights and opportunities in post-mining land use. I.e, they must demand a seat at the table from day one, as their vision for the land’s future is not a suggestion; it is a requirement.

CONCLUSION

A mine’s true legacy is not just the minerals it extracts, but the land it leaves behind. Sustainable mine closure transforms a potential disaster into an opportunity, restoring ecosystems, creating jobs, and protecting future generations. As Nigeria intensifies its mining drive, this forgotten chapter in sustainability can no longer be ignored.

REFERENCES

[1] How mining pits degrade the environment, endanger lives in… (2022) Daily Trust. Available at: https://dailytrust.com/how-mining-pits-degrade-environment-endanger-lives-in-plateau/ (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

[2] Closure and rehabilitation of Ranger Mine – DCCEEW. Available at: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/science-research/supervising-scientist/ranger-mine/closure-rehabilitation (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

[3] Outokumpu Old Mine and mining museum (no date) ERIH. Available at: https://www.erih.net/i-want-to-go-there/site/outokumpu-old-mine-and-mining-museum (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

[4] Is it possible to convert old coal mines into successful farms? Available at: https://www.miningweekly.com/article/is-it-possible-to-convert-old-coal-mines-into-successful-farms-2022-06-24-1 (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

[5] Pimmy (2020) Mae moh lignite mine , Explore Lampang & Lamphun. Available at: https://www.tourismlampang-lamphun.com/lampang/mae-moh-lignite-mine/ (Accessed: 19 August 2025).

[6] Collaborative Landscape Restoration after mining operation in Ghana (2020) The 4 Returns Community Platform. Available at: https://4returns.commonland.com/landscapes/collaborative-landscape-restoration-after-mining-operation-in-ghana/ (Accessed: 19 August 2025).